|

Ruskin at Notebook M2 p.117 contrasts the ‘nationality’ of Gothic with the universalism of Palladio and Sansovino. The comment does not do justice to the differences between Palladio and, for example, the Venetian character of Sansovino’s Library. It remains true, however, that Venetian Gothic, like any other Gothic and unlike Palladio, was distinctive in its national expression of the nature of Gothic, its moral and architectural strength.

In Venetian ecclesiastical architecture a ‘peculiar and very primitive form of pointed Gothic had arisen in ecclesiastical architecture’ (Works, 9.42). The examples cited by Ruskin are San Giacomo dell'Orio, San Giovanni in Bragora, and the Carmini.

Venetian policy repressed the power of the church. Gothic architecture in Venice therefore became divided between ecclesiastical and civil. The ecclesiastical was ‘an ungraceful yet powerful form of Western Gothic common to the whole peninsula’, though with Venetian mouldings. The representative building were said by Ruskin to be the Frari, SS Giovanni e Paolo, Santo Stefano.

Secular Gothic architecture in Venice was ‘rich, luxuriant and entirely original’ and was formed from the Venetian-Arab by the influence of Dominican and Franciscan architecture, particularly the traceries of the Frari seen by Ruskin as its most novel features. The style is represented by the Ducal Palace and ‘other principal Gothic palaces’ (Works, 9.43). Even in these buildings there is evidence of the degradation of Gothic. Similarly the Ducal Palace Series of Capitals of Lower Arcade show evidence of decline and degradation, though the earlier originals of the capitals, in their leafage as in their figures, define for Ruskin the best of Venetian Gothic sculpture, just as the sculpture of porches of Lyon is ‘by far the most wonderful I have yet seen in northern Gothic’ (Notebook M2 p.170).

Most of the material in all the notebooks may be seen as a series of attempts to describe the evolution of Venetian Gothic. However at Notebook M p.47 on November 23rd Ruskin wrote that he obtained ‘today a clue to the whole system of pure Venetian Gothic’. That system is set out at Notebook M p.45; Notebook M p.47; Notebook M p.48; Notebook M p.50; Notebook M p.51; Notebook M p.57; Notebook M p.58.

At Notebook M p.48L Pisa is said to be the starting point, presumably for all Italian Gothic:

|

In Venice however, in Ruskin’s narrative in M, the development of Gothic was inflected by Byzantine and Arab influences represented in the visual culture of Venice, particularly the architecture of S. Mark’s, its stilted arches, its capitals, its marble cladding, and the ‘Saracenic’ arches of St Mark’s, which led to the ‘sharpening of the bend of the arch’ in Venice:

|

|

Compare the Byzantine Lily and basketworks capitals of San Vitale, at Ravenna at here.

|

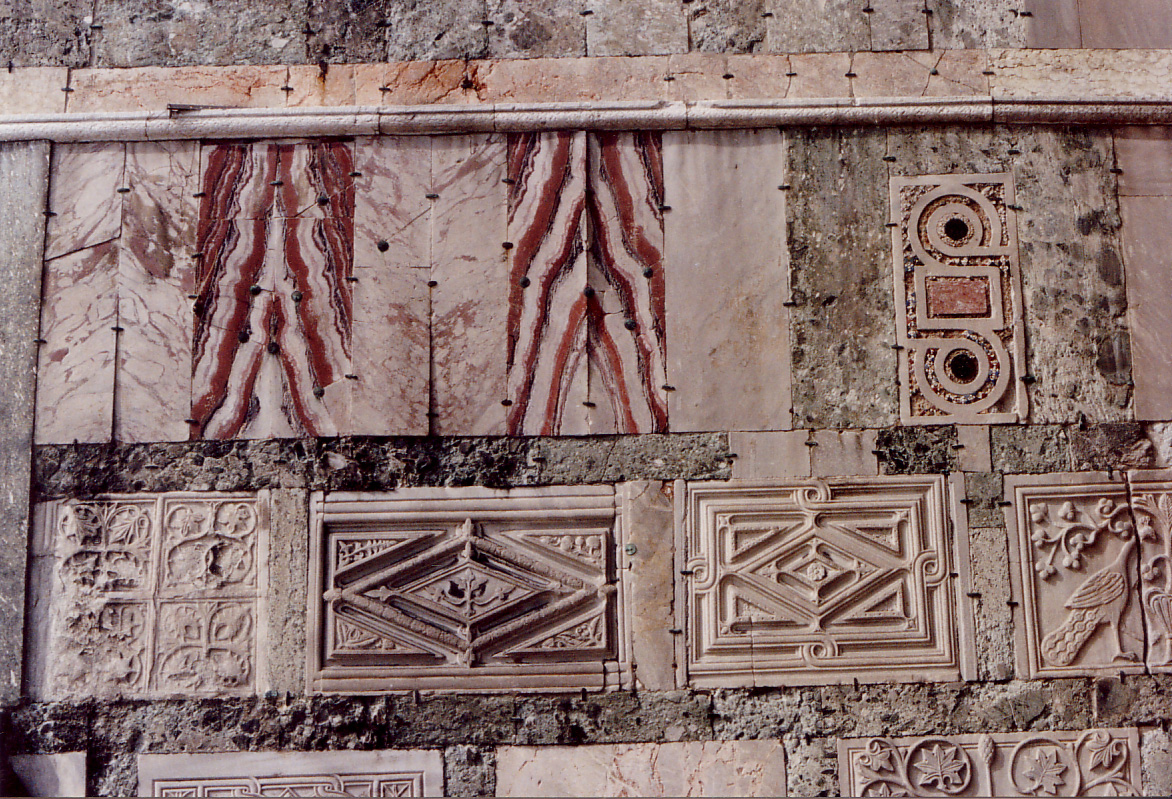

For ‘Arab’ work in St. Mark’s see the diagram of the Treasury Door of St.Mark’s at Bit Book p.50 and the image of Porta dei Fiori from Ruskin’s Rudimentary Series here.

A detail of the Porta dei Fiori is shown in a modern photograph:

|

At the top of Notebook M p.46 is what appears to be the first attempt to set out, in words and diagrams, the 1st order (the stilted arches, round, and seen by Ruskin as typically Byzantine), 2nd order and 3rd order of Venetian arches. In the entry dated November 23rd at Notebook M p.47, with diagrams at Notebook M p.47L, the 1st order, 2nd order, 3rd order, and 4th order are described and illustrated in sequence, and at Notebook M p.47L there is also a diagram of the 5th order. Howard (2002) p.98 points out that Ruskin accepted that the orders did not ‘follow each other in a clear and systematic sequence, but overlap one another for long periods. In a diagram at House Book 2 p.4L Ruskin draws attention to a clear example of a conjoined 4th order and 5th order in a single building, the Palazzo Trevisan degli Ulivi / Olivi, Dorsoduro 809, Nadali & Vianello (1999) Tav. 50, and he comments on it at House Book 2 pp.4L and 4:

|

At Notebook M pp.73L and 73 and Notebook M p.74 Ruskin brings together all his drawings of capital sections to define a developmental sequence.

At Notebook M pp.213-215 the niches of St. Mark’s are used to provide a case study of the best of Venetian Gothic and of the degradation of Gothic in Venice.

What is now seen as the front of M2 is used by Ruskin to define developmental sequences in Venetian Gothic architecture, based on his own observations, and on:

At Verona Book p.41 Ruskin suggests in relation to Venetian Gothic that the ‘proportional superimposition of small on large is a peculiar characteristic of all good styles’.

|

|

|

[Version 0.05: May 2008]