2 Controlling the CUSUM and Other Models

In this chapter, we explore the properties of the CUSUM test for detecting a change in mean, and this will allow us how to determine appropriate thresholds, and explore its properties when a changepoint is present.

We will employ some concepts from asymptotic theory: in time series analysis, an asymptotic distribution refers to the distribution that our test statistic approaches as the length of the time series \(n\) becomes very large.

2.1 The asymptotic distribution of the CUSUM statistics

If \(z_1, \cdots, z_k\) are independent, standard Normal random variables, then:

\[ \sum_{i=1}^k z^2_i \sim \chi^2_k, \]

where \(\chi^2_k\) is a chi-squared distribution with \(k\) degrees of freedom. The chi-squared distribution is a continuous probability distribution that models the sum of squares of k independent standard normal random variables: we have met the chi-squared distribution already in hypothesis testing and constructing confidence intervals. The shape of the distribution depends on its degrees of freedom. For \(k=1\), it’s highly skewed, but as \(k\) increases, it becomes more symmetric and approaches a normal distribution.

Last week, we found out that, under the null hypothesis of no change:

\[\frac{1}{\sigma}\sqrt{\frac{\tau(n-\tau)}{n}} ( \bar{y}_{1:\tau} - \bar{y}_{(\tau+1):n}) \sim N(0, 1).\]

Therefore, our test statistics for a fixed \(\tau\):

\[\frac{C_\tau^2}{\sigma^2} \sim \chi^2_1.\]

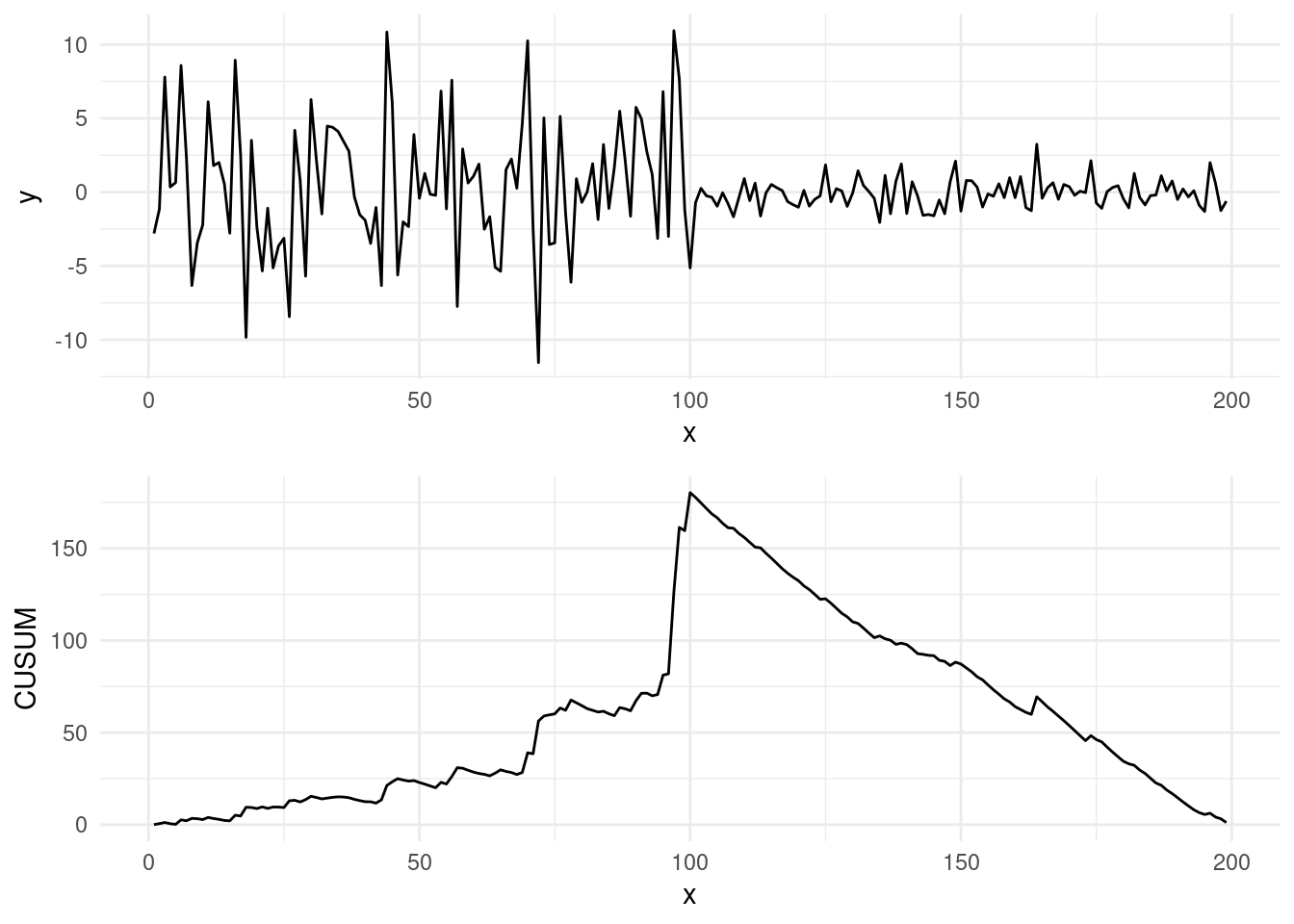

If we take the example of last week, and remove the changepoint, we can observe that the cusum statistics stays constant, and relatively small:

However, as the change is unknown, our actual test statistic for detecting a change is \(\max_\tau C_\tau^2/σ^2\).

For this reason, calculating the distribution of this maximum ends up being a bit more challenging…

So far, we only studied the behaviour of the statistics for one fixed \(\tau\), however, when comparing the maximums, the values of \(C_\tau\) are in fact not independent across different \(\tau\)s.

As we will learn later, the CUSUM is a special case of a LR test, as setting the size of the actual change in mean to 0 effectively removes the changepoint parameter from the model. For this reason, the usual regularity conditions for likelihood-ratio test statistics don’t apply here.

2.1.1 Controlling the max of our cusums

Fortunately, for controlling our CUSUM test, we can use the fact that \((C_1, ..., C_{n-1})/ \sigma\) are the absolute values of a Gaussian process with mean 0 and known covariance, and there are well known statistical results that can help us in our problem. Yao and Davis (1986), in fact, show that the maximum of a set of Gaussian random variables is known to converge to a Gumbel distribution, described by the following equation:

\[ \lim_{n→\infty} \text{Pr}\{a_n^{-1}(\max_\tau C_\tau/\sigma - b_n) ≤ u_\alpha\} = \exp\{-2(\pi)^{-1/2}\exp(-u_\alpha)\}, \tag{2.1}\]

where \(a_n = (2 \log \log n)^{-1/2}\) and \(b_n = a_n^{-1} + 0.5a_n \log \log \log n\) are a scaling and a centering constant.

The right side of this equation is the CDF of a Gumbell distribution. As we learned from likelihood inference, to find the threshold \(c_{\alpha}\) for a given false probability rate, we first set the right-hand side equal to \(1 - \alpha\), and solve for \(u_\alpha\). This gives:

\[ u_\alpha = -\log\left( -\frac{\log(1-\alpha)}{2(\pi)^{-1/2}} \right). \]

Then, we can find the critical value by looking into the left side of the equation:

\[ \tilde{c} = (a_n u_\alpha + b_n), \]

To find the threshold, as \(\max_\tau \frac{C_{\tau}^2 }{\sigma^2} > c\), we just have to square our value above, e.g. \(c_\alpha = \tilde{c}^2\).

This asymptotic result suggests that the threshold \(c_\alpha\) for \(C_\tau^2/\sigma^2\) should increase with \(n\) at a rate of approximately \(2 \log \log n\). Given that this is a fairly slow rate of convergence, this suggests that the threshold suggested by this asymptotic distribution can be conservative in practice, potentially leading to detect less changepoints than what actually exist.

In practice, it’s often simplest and most effective to use Monte Carlo methods to approximate the null distribution of the test statistic. This can be done via the following process:

Simulate many (say \(M\)) time series under the null hypothesis (no changepoint),

Calculate the test statistic \(\max_\tau \frac{C_{\tau}^2 }{\sigma^2}\) for each one of the replicates.

Set the threshold to be the \((1-\alpha)\) percentile of the distribution of the test statistics from simulated data.

This leads to have less conservative thresholds. However, one clear drawback, this approach is computationally intensive (especially for large \(n\) and large \(M\)).

Theoretical vs Empirical Thresholds The figure below shows, for various levels of \(\alpha = 0.01, 0.05, 0.1\), thresholds \(c_\alpha\) computed from the theoretical distribution of Equation 2.1 against the Monte Carlo thresholds obtained from empirical simulations under the null.

We will see how to compute in practice the theoretical and empirical thresholds in the Lab!

2.2 The Likelihood Ratio Test

The CUSUM can be viewed as a special case of a more general framework based on the Likelihood Ratio Test (LRT). This allow us to test for more general settings, beyond simply detecting changes in the mean.

In general, the Likelihood Ratio Test is a method for comparing two nested models: one under the null hypothesis, which assumes no changepoint, and one under the alternative hypothesis, which assumes a changepoint exists at some unknown position \(\tau\).

Suppose we have a set of observations \(y_1, y_2, \dots, y_n\). Under the null hypothesis \(H_0\), we assume that all the data is generated by the same model without a changepoint. Under the alternative hypothesis \(H_1\), there is a single changepoint at \(\tau\), such that the model for the data changes after \(\tau\). The LRT statistic is given by:

\[ LR_\tau = - 2 \log \left\{ \frac{\max_{\theta} \prod_{t=1}^n f(y_{t}, \theta)}{\max_{\theta_1, \theta_2} [(\prod_{t=1}^\tau f(y_{t}, \theta_1))(\prod_{t=\tau+1}^n f(y_{t}, \theta_2)]} \right\}, \tag{2.2}\]

with \(f(y_{t}, \theta)\) being the likelihood for data point \(y_{t}\) and segment parameter \(\theta\). The LRT compares the likelihood of the data under two models to determine which one is more likely: the enumerator, is the likelihood under the null hypothesis of no changepoint, while the denominator represents the likelihood of the data under the alternative hypothesis, where we optimise for two different parameters before (\(\theta_1\)) and after the changepoint at \(\tau\) (\(\theta_2\)).

2.2.1 Example: Gaussian change-in-mean

As a first example, we show how the CUSUM statistics is nothing but a specific case of the GLR. To see this, we start from our piecewise costant signal, plus noise, \(y_t = \mu_t + \epsilon_t, \quad t = 1, \dots, n\). Under this model our data, a linear combination of a Gaussian, is distributed as:

\[ y_{t} \sim N(\mu_t, \sigma^2), \quad t = 1, \dots, n \]

Our p.d.f. will be:

\[ f(y_t, \mu) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi \sigma^2}} \exp\{-\frac{1}{2 \sigma^2} (y_t - \mu)^2\}. \]

Therefore, to obtain the likelihood ratio test statistic, we plug our Gaussian p.d.f. into the LR above, and take the logarithm:

\[\begin{align*} LR_\tau = & -2 \left[ \max_{\mu} \left( -\frac{1}{2\sigma^2} \sum_{t=1}^n (y_t - \mu)^2 \right) - \max_{\mu_1, \mu_2} \left( -\frac{1}{2\sigma^2} \left( \sum_{t=1}^\tau (y_t - \mu_1)^2 + \sum_{t=\tau+1}^n (y_t - \mu_2)^2 \right) \right) \right] \\ &- n \log(2\pi \sigma^2) + \tau \log(2\pi \sigma^2) + (n - \tau) \log(2\pi \sigma^2). \end{align*}\]

This simplifies to:

\[ = \frac{1}{\sigma^2} \left[ \min_{\mu} \sum_{t=1}^n (y_t - \mu_1)^2 - \min_{\mu_1, \mu_2} \left( \sum_{t=1}^\tau (y_t - \mu_1)^2 + \sum_{t=\tau+1}^n (y_t - \mu_2)^2 \right) \right]. \]

To solve the minimization over \(\mu_1\) and \(\mu_2\), we plug-in values \(\hat\mu = \bar{y}_{1:n}\) on the first term, and \(\hat\mu_1 = \bar{y}_{1:\tau}\), \(\hat\mu_2 = \bar{y}_{(\tau+1):n}\) for the second term:

\[ LR_\tau = \frac{1}{\sigma^2} \left[ \sum_{t=1}^n (y_t - \bar{y}_{1:n})^2 - \sum_{t=1}^\tau (y_t - \bar{y}_{1:\tau})^2 - \sum_{t=\tau+1}^n (y_t - \bar{y}_{(\tau+1):n})^2 \right]. \]

This is the likelihood ratio test statistic for a change in mean in a Gaussian model, which is essentially the CUSUM statistics squared, rescaled by the known variance:

\[ LR_\tau = \frac{C_\tau^2}{\sigma^2}. \]

It is possible to prove this directly with some tedious computations.

Proof. We start by writing down \(\sigma^2 LR\). This will be:

\[ \sigma^2 LR_\tau = \sum_{t=1}^{n} (y_t - \bar{y}_{1:n})^2 - \sum_{t=1}^{\tau} (y_t - \bar{y}_{1:\tau})^2 - \sum_{t=\tau+1}^{n} (y_t - \bar{y}_{\tau+1:n})^2. \]

Now we need to expand each term. Starting with the first:

\[ \sum_{t=1}^{n} (y_t - \bar{y}_{1:n})^2 = \sum_{t=1}^{n} y_t^2 - 2 \bar{y}_{1:n} \sum_{t=1}^{n} y_t + n \bar{y}_{1:n}^2. \]

As \(\sum_{t=1}^{n} y_t = n \bar{y}_{1:n}\), we notice that we can simplify the last two terms. We are left with:

\[ \sum_{t=1}^{n} (y_t - \bar{y}_{1:n})^2 = \sum_{t=1}^{n} y_t^2 - n \bar{y}_{1:n}^2. \]

We proceed similarly for the other two terms:

\[ \sum_{t=1}^{\tau} (y_t - \bar{y}_{1:\tau})^2 = \sum_{t=1}^{\tau} y_t^2 - \tau \bar{y}_{1:\tau}^2, \quad \sum_{t=\tau + 1}^{n} (y_t - \bar{y}_{\tau+1:n})^2 = \sum_{t=\tau+1}^{n} y_t^2 - (n-\tau) \bar{y}_{\tau+1:n}^2. \]

Putting all together, and getting rid of the partial sums, we are left with:

\[ \sigma^2 LR_\tau = - n \bar{y}_{1:n}^2 + \tau \bar{y}_{1:\tau}^2 + (n - \tau) \bar{y}_{\tau+1:n}^2. \]

Now, recall that \(\bar{y}_{1:n} = \frac{1}{n} \left[ \tau \bar{y}_{1:\tau} + (n - \tau) \bar{y}_{\tau+1:n} \right]\), and:

\[ \bar{y}_{1:n}^2 = \frac{1}{n^2} \left[ \tau^2 \bar{y}_{1:\tau}^2 + 2 \tau (n - \tau) \bar{y}_{1:\tau}\bar{y}_{\tau+1:n} + (n - \tau)^2 \bar{y}_{\tau+1:n}^2 \right]. \]

Plugging in this into our LR:

\[\begin{align} \sigma^2 LR_\tau &= - \frac{\tau^2}{n} \bar{y}_{1:\tau}^2 - \frac{2 \tau (n - \tau)}{n} \bar{y}_{1:\tau}\bar{y}_{\tau+1:n} - \frac{(n - \tau)^2}{n} \bar{y}_{\tau+1:n}^2 - \tau \bar{y}_{1:\tau}^2 - (n - \tau) \bar{y}_{\tau+1:n}^2=\\ &= \frac{\tau (n - \tau)}{n} \bar{y}_{1:\tau}^2 - \frac{2 \tau (n - \tau)}{n} \bar{y}_{1:\tau}\bar{y}_{\tau+1:n} + \frac{\tau (n - \tau)}{n} \bar{y}_{\tau+1:n}^2 = \\ &= \frac{\tau (n - \tau)}{n} (\bar{y}_{1:\tau}^2 - 2 \bar{y}_{1:\tau}\bar{y}_{\tau+1:n} + \bar{y}_{\tau+1:n}^2)=\\ &= \frac{\tau (n - \tau)}{n} (\bar{y}_{1:\tau} - \bar{y}_{\tau+1:n})^2=\\ &= C_\tau^2. \end{align}\]

This gives us \(LR_\tau = \frac{C_\tau^2}{\sigma^2}\).

2.3 Towards More General Models

The great thing of the LR test is that it’s extremely flexible, allowing us to detect other changes then the simple change-in-mean case. As before, the procedure is to compute the LR test conditional on a fixed location of a changepoint, e.g. \(LR_\tau\), and range across all possible values for \(\tau\) to find the test statistics for our change.

2.3.1 Change-in-variance

To this end we will demonstrate how to construct a test for Gaussian change-in-variance, for mean known. For simplicity, we will call our variance \(\sigma^2 = \theta\), our parameter of interest, and without loss of generality, we can center our data on zero (e.g. if \(x_t \sim N(\mu, \theta)\), then \(x_t - \mu = y_t \sim N(0, \theta)\)). Then, our p.d.f for one observation will be given by:

\[ f(y_t | \theta) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi \theta}} \exp\{-\frac{y_t^2}{2 \theta}\}. \]

Plugging in the main LR test formula, we find:

\[ LR_\tau = - 2 \log \left\{ \frac{\max_{\theta} \prod_{t=1}^n \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi\theta }} \exp\{-\frac{y_t^2}{2 \theta}\}}{\max_{\theta_1, \theta_2} [(\prod_{t=1}^\tau \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi\theta_1}} \exp\{-\frac{y_t^2}{2 \theta_1}\})(\prod_{t=\tau+1}^n \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi\theta_2}} \exp\{-\frac{y_t^2}{2 \theta_2}\}]} \right\} \]

And taking the log, and simplifying over the constant gives us:

\[\begin{align} LR_\tau &= -\max_\theta \sum_{t = 1}^n \left(- \log(\theta) - \frac{y^2}{\theta} \right) + \max_{\theta_1, \theta_2} \left[ \ \sum_{t = 1}^\tau \left( - \log(\theta_1) - \frac{y^2}{\theta_1} \right) + \sum_{t = \tau+1}^n \left( - \log(\theta_2) - \frac{y^2}{\theta_2} \right) \right] = \\ & = \min_\theta \sum_{t = 1}^n \left( \log(\theta) + \frac{y^2}{\theta} \right) - \min_{\theta_1, \theta_2} \left[ \ \sum_{t = 1}^\tau \left( \log(\theta_1) + \frac{y^2}{\theta_1} \right) + \sum_{t = \tau+1}^n \left( \log(\theta_2) + \frac{y^2}{\theta_2} \right) \right] \end{align}\]

Now to solve the minimisation, we focus on the first term:

\[ f(y_{1:n}, \theta) = \sum_{t = 1}^n \left( \log(\theta) + \frac{y^2}{\theta} \right) = \left( n \log(\theta) + \frac{\sum_{t = 1}^n y^2}{\theta} \right). \]

Taking the derivative with respect to \(\theta\), gives:

\[ \frac{d}{d\theta} f(y_{1:n}, \theta) = \frac{n}{\theta} - \frac{\sum_{t = 1}^n y^2}{\theta^2}. \]

Setting equal to zero and solving for \(\theta\):

\[ n \theta - \sum_{t = 1}^n y^2 = 0 \]

Which gives us: \(\hat\theta = \frac{\sum_{t = 1}^n y^2}{n} = \bar S_{1:n}\) the sample variance.

Solving the optimization for \(\theta_1\) and \(\theta_2\) similarly, gives us the values \(\hat \theta_1 = \bar S_{1:\tau}, \ \hat \theta_2 = \bar S_{(\tau+1):n}\).

Now, as \(f(y_{1:n}, \hat{\theta}) = n \log( \bar{S}_{1:n}) + n\) (why?) the final LR test simplifies to:

\[ LR_\tau = \left[ n \log(\bar S_{1:n}) - \tau \log(\bar S_{1:\tau}) - (n - \tau) \log(\bar S_{(\tau + 1):n}) \right] \]

2.3.2 Change-in-slope

Another important example, and an alternative to detecting a change-in-mean, is detecting a change in slope. In this section, we assume the data is still modeled as a signal plus noise, but the signal itself is a linear function of time (e.g. non-stationary, with a change!). Graphically:

More formally, let our data be modeled as:

\[ y_t = f_t + \epsilon_t, \ \epsilon_t \sim N(0, 1) \quad t = 1, \dots, n. \] In this scenario, for simplicity, we assume a known constant variance, which without loss of generality, we take to be 1.

Under the null hypothesis \(H_0\), we assume that the signal is linear with a constant slope over the entire sequence, i.e.,

\[ f_t = \alpha_1 + t\theta_1, \quad t = 1, \dots, n, \]

where \(\alpha_1\) is the intercept, and \(\theta_1\) is the slope. However, under the alternative hypothesis \(H_1\), we assume there is a changepoint at \(\tau\) after which the slope changes. Thus, the signal becomes:

\[ f_t = \alpha_1 + t\theta_1, \quad t = 1, \dots, \tau; \quad f_t = \alpha_2 + t \theta_2, \quad t = \tau+1, \dots, n, \]

where \(\alpha_2\) is the new intercept, and \(\theta_2\) is the new slope after the changepoint. In other words, the model is showing a piecewise linear mean.

For this model, the log-likelihood ratio test statistic can be written as the square of a projection of the data onto a vector \(v_\tau\), i.e.,

\[ LR_\tau = \left( v_\tau^\top y_{1:n} \right)^2, \]

where \(v_\tau\) is a contrast vector that is piecewise linear with a change in slope at \(\tau\). This vector is constructed such that, under the null hypothesis, the vector \(v_\tau^\top y_{1:n}\) has variance 1, and \(v_\tau\^\top y_{1:n}\) is invariant to adding a linear function to the data. These properties uniquely define the contrast vector \(v_\tau\), up to an arbitrary sign. Computations on how to obtain this likelihood ration test, and how to construct this vector are beyond the scope of this module, but should you be curious those are detailed in Baranowski, Chen, and Fryzlewicz (2019).

2.3.3 Revisiting our Simpsons data (again!)

So, going back to the Simpsons example… We mentioned how the belowed show rose rapidly to success, and at one point, started to decline… A much better model would therefore be our change-in-slope model!

To run the model, we can take advantage of the changepoint package, which by default is a multiple changepoint package (we will see these in the next week), but whose simplest case implements exactly our change-in-slope LR test.

Before we proceed, we need to load, clean and standardize our data:

# Load Simpsons ratings data

simpsons_episodes <- read.csv("extra/simpsons_episodes.csv")

simpsons_episodes <- simpsons_episodes |>

mutate(Episode = id + 1, Season = as.factor(season), Rating = tmdb_rating)

simpsons_episodes <- simpsons_episodes[-nrow(simpsons_episodes), ]

y <- simpsons_episodes$RatingWe can then run our model with:

library(changepoint)

data <- cbind(y, 1, 1:length(y))

out <- cpt.reg(data, method="AMOC") # AMOC is short for "At Most One Change"

print(paste0("Our changepoint estimate (chagepoints): ", cpts(out)))[1] "Our changepoint estimate (chagepoints): 176"plot(out)

We can see that we now find a significant changepoint prior to episode The Simpsons Spin-Off Showcase, which is anthology episode well over into season 8, which, according to our method, is the beginning of the decline! However, some among you, might have noticed that there are more then one changes in this dataset… We will see, in fact, how we can improve on our estimation in the following weeks!

2.4 Exercises

2.4.1 Workshop 2

Consider an independent Bernoulli time series, \(y_t \sim \text{Bernoulli}(p)\), for \(t = 1, \dots, n\), where \(y_t \in {0, 1}\). In this question, you will compute the Likelihood Ratio (LR) test statistic for detecting a change in the success probability \(p\) at some unknown point \(\tau \in {1, \dots, n-1}\).

Write down the probability mass function (pmf) of the Bernoulli distribution under the null hypothesis (no change), and derive the corresponding Maximum Likelihood Estimator (MLE) for \(p\). Then, extend this formulation to the alternative hypothesis, where the success probability changes at \(\tau\).

Using the MLEs from part (a), construct the log-likelihood ratio according to the general expression for the Likelihood Ratio test statistic, as defined in Equation Equation 2.2.

2.4.2 Lab 2

Write a function, that taking as input \(n\) and a desired \(\alpha\) level for false positive rate, returns the threshold for the cusum statistics, according to Section Section 2.1.1.

Construct a function that, taking as input \(n\), a desired \(\alpha\) , and a

replicatesparameter, runs a Monte Carlo simulation to tune an empirical penalty for the CUSUM change-in-mean on a simple Gaussian signal. Tip: You can reuse the function for computing the CUSUM statistics that you built the last weekCompare for a range of increasingly values of n, e.g. \(n = 100, 500, 1000, 10.000\), and for few desired levels of alpha, the Monte Carlo threshold with the theoretically justified threshold. Plot the results, to recreate the plot above.

Using the Test the Simpsons dataset, and the monte carlo threshold, find a critical level for your CUSUM statistics, and declare a change with the change-in-mean model.