IPP 507: Environmental Ethics

AWAYMAVE - The Distance Mode of MA in Values and the Environment at Lancaster University

Block 2 - Culture, Art and Environment

| Tutor Details | Biblio | Assessment | Resources | discussion |

| Appreciating art and nature | |

| Cultural Landscapes |

In this block we begin to explore contemporary approaches to aesthetic experience of nature, in particular, the differences between art appreciation and aesthetic appreciation of environments. We also consider the experience of environments that fall between nature and art, such as agricultural landscapes and environmental artworks.

Appreciating art and nature

Now read chapter 3, pp. 52-70 Aesthetics of the Natural Environment and Donald Crawford, ‘Comparing Natural and Artistic Beauty’ from Kemal and Gaskell. |

Further reading:

R.W. Hepburn, ‘Contemporary Aesthetics and the Neglect

of Natural Beauty’, from Wonder and Other Essays (Edinburgh

1984);

Yuriko Saito, ‘Environmental Directions for Aesthetics and the Arts’,

in Berleant, ed., Environment and the Arts, 2002.

The identification of the aesthetic with art and the neglect of natural beauty

In Block 1, we looked at some fairly traditional theories of aesthetic

experience, as set out in Kant and others and as developed in theories

of the beautiful, sublime and picturesque.

Where does that leave us in relation to trying to understand aesthetic appreciation of environments in a contemporary context? What has been happening in aesthetics more recently in relation to environmental appreciation?

Philosophical aesthetics in the late 19th and throughout the 20th century has been almost exclusively concerned with art. The reason for this lies in radical movements in the artworld. Art moved from being representational to expressive to the avant-garde. It became important to conveying social and political concerns. This has made art of great interest to philosophers.

In the later 20th c. there has been a slow movement towards thinking about aesthetic experience in non-artistic contexts, that is, in the everyday context or in the context of the natural and built environments. This is probably a result of influences from outside philosophical aesthetics such as environmental activism and postmodernism.

As Ronald Hepburn pointed out in his landmark paper, ‘Contemporary Aesthetics and the Neglect of Natural Beauty’ (originally published in 1966), the focus on art has been the case, with few exceptions, until the late 1960’s and early 1970’s.

Aesthetics of the natural environment is still relatively neglected in mainstream philosophical aesthetics. There is change, however, with more books and journal articles coming out. Nature is being noticed once again in philosophical aesthetics (see for example the special issue on environmental aesthetics of the Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 1998). But some views in the contemporary debate about aesthetics of nature still owe their allegiance to art - art as paradigm of aesthetic appreciation.

Think

Think

How much should we bring from art to nature when trying to understand what aesthetic appreciation of nature involves? Do we start from art and work towards nature or from nature to art, or, as Arnold Berleant suggests, begin from an environmental standpoint, leaving paradigms of artistic appreciation behind?

The Range of Environments

Before launching into a philosophical consideration of differences between aesthetic experience of nature and art, it is useful to recognise the range of environments that exist.

The following sets out the range from wild nature to urban environments, with the more natural on one side and the more artefactual on the other:

‘wilderness’ and minimally modified nature: national

parks; nature reserves

modified nature: countryside; agricultural landscapes; parks; gardens; suburbs

urban: suburbs; towns; cities

How might appreciation of wild nature differ from appreciation of, say, a city park? Are there any aspects of the experiences in common? Post your answer to this on the discussion site.

Differences between appreciation of art and nature

Most philosophers (at least going back to Hepburn’s paper) argue that there are important differences that mark out natural environmental appreciation from artistic appreciation. But at the same time, it is a good idea to keep an open mind. With the advent of installation art and other artworks that are environmental in some sense (apart from actual artworks ‘in the land’ and artworks described as environmental artworks, which we look at in a later section of this block), some of the differences laid out in Chapter 3 of the course text (and noted here below) are open to revision.

The nature of the object

One important factor which determines differences between nature and art appreciation is the nature of the aesthetic object, which includes its origins.

Art and intention

Here it is important to remember that art is first and foremost an intentional object, a type of object crafted by a human artist (unless you think non-human animals also create art) with a set of intentions or aims.

Art originates in human production and this informs our appreciation of it. In the background of appreciation (and sometimes in the foreground too) is an awareness that it is a created object with, in many cases, meanings being conveyed or emotions being expressed, by the artist, in the work.

Consider the classic, oft-cited case of discovering a piece of driftwood on a beach. You pick it up, marvel at its amazing shapes and contours, all formed by its life in the sea. But low and behold, as you turn it over, you find someone’s name carved in the wood. Could this actually be a piece of sculpture?! How does your appreciation of the wood’s qualities shift when you discover its origins are artistic rather than natural?

Nature and origin

By contrast, if we are talking about environments on the more natural end of the scale, rather than cultural environments, then the aesthetic object/environment has natural origins rather than human ones. Therefore, we do not appreciate nature as a created object. Our appreciation is not directed by artistic aspects of the object, but more by the object’s qualities and, of course, our own choices (Hepburn thinks that nature appreciation thus allows more freedom on the part of the appreciator).

However, if you adopt a theistic perspective on nature’s creation, then you may argue that nature is god’s work. You may even hold that nature is god’s ‘art work’.

Art has boundaries/conventions

Consider traditional art forms such as painting, theatre, sculpture, musical performances on a stage, etc. In these kinds of cases, the object of aesthetic appreciation is set apart from us by some type of artistic convention and often, literally, with stage, frame, screen, etc. Some contemporary artworks, of course, challenge such conventions. Also, consider music – is this a kind of environmental appreciation?

Nature comes without frames

By contrast, nature has no boundaries except the ‘perceptual frame’ we may put around it as when we view a landscape or when we focus attention to particular areas of an environment. Consider reaching down and touching a mushroom on a forest floor, versus beholding a view through the forest and into the distance. (There are of course boundaries in terms of fences, viewing points and other structures that may determine how we engage with natural environments.)

Context

A second key factor which determines differences between art and nature appreciation lies in the context or situation of appreciation.

Multi-sensuous experience, immersion, and the dynamic and transient character of nature

Because art objects are physically bounded, our various aesthetic perspectives and engagement with them is determined by those boundaries. Hence, the scope of our aesthetic experience is limited (except for some types of contemporary art which encourage exploration of the artwork as a sort of artefactual environment).

Natural objects offer the possibility of a multi-sensuous

experience due to the fact that we often engage with natural objects through

becoming immersed in an environment.

We can move through the natural objects we experience. Standing still

to contemplate a wild flower is one way to appreciate the environment.

But we are also able to walk in it, climb it, fly through it, sink

into it, and swim through it.

With nature, total immersion in the aesthetic object is possible. Immersion reveals yet another relevant feature of natural objects: nature’s dynamic character – the fact that it is ever-changing (even if at a very slow pace), and often transient, especially organic nature.

Natural objects change due to growth, decay, erosion, climate changes or the inherent movement of certain objects like the earth or the sea. This is a central feature of environments.

We may choose to take up a variety of perspectives in light of such changes, but more often these changes force new aesthetic perspectives on us.

The indeterminacy of natural objects/environments widens the scope of our aesthetic experience in equally indeterminate ways. The complexity of such objects provides the possibility of rich and rewarding aesthetic experience, but such an experience is made by the percipient - we must take up the challenge that natural objects offer, as Hepburn urges:

‘Aesthetic experience of nature can be meagre, repetitive and undeveloping. To deplore such a state of affairs and to seek amelioration is to accept an ideal which can be roughly formulated thus. It is the ideal of a rich and diversified experience, far from static, open to constant revision of viewpoint and of organisation of the visual field, constant increase in scope of what can be taken as an object of rewarding aesthetic contemplation, an ideal of increase in sensitivity and in mobility of mind in discerning expressive qualities in natural objects.’ (R.W. Hepburn, ‘Nature in the Light of Art’, from his collection of essays, Wonder and Other Essays, 1984, p. 41)

Short exercise

Imagine yourself (or better, try it outdoors) immersed in different types of natural environments. What are some of the perspectives you might take up? What different senses come into play? How does immersion in environments affect appreciation?

Cultural Landscapes

Now read chapter 3, pp. 70-82 of Aesthetics of the Natural Environment and Stephanie Ross, ‘Gardens, Earthworks and Environmental Art’ in Kemal and Gaskell |

Further reading for this section:

Chapters 11 and 12 in Allen Carlson in Aesthetics and

the Environment, 2000;

and see entries under ‘gardens’ and ‘environmental art’

in the bibliography.

Sally Schauman, ‘The Garden and the Red Barn: The Pervasive Pastoral

and Its Environmental Consequences,’ Journal of Aesthetics and

Art Criticism, 56:2, 1998.

Introduction

Aesthetic experiences of nature can foster attachments to particular environments and places, and to species or other things that make up these environments. We seek out these places and environments time and time again because we value them. These attachments are developed through direct or immediate experience of the natural world.

But our relationship to nature is also developed, aesthetically and non-aesthetically, through cultural landscapes – through human interaction with the land; through all sorts of ways we engage with nature - in creating environmental artworks; in creating gardens; in farming fields, etc.

In this section, we consider the character of appreciation of the mixed environments that are often referred to as cultural landscapes. In particular, we look at environmental artworks and agricultural landscapes.

Appreciating environments and objects between nature and art

Objects and environments which lie between nature and art form an interesting category of objects of aesthetic appreciation. The combination of artefact and nature in these objects/environments creates a complex object of appreciation, and even perhaps what one philosopher has described as ‘difficult aesthetic appreciation’.

Allen Carlson cites various cases of difficult aesthetic appreciation, including, 'farming, mining, urban sprawl, and other kinds of human intrusions on the landscape…graffiti on rocks, initials carved in trees, artificially designed plants and animals, and even tattoos', but also Japanese gardens, topiary gardens and environmental artworks. (Allen Carlson, Aesthetics and the Environment: The Appreciation of Nature, Art and Architecture (London and New York: Routledge, 2000), p. 165)

The effect on appreciation is that it is, ‘difficult because both of the natural and the artificial are independently present, each requires different kinds of appreciation, and thus together they force the appreciator to perform various kinds of appreciative gymnastics.’ (Carlson, 2000, p. 165-6)

In addition to being complex objects of appreciation, the generation of mixed environments involves a relationship between humans and nature. Let's turn now to thinking about that relationship in the context of environmental art.

Environmental Art

What is environmental art and land art? They comprise a great range of artworks, from small sculptural objects, to grand gestures in the land, from ephemeral pieces that do not last, to permanent works, most of which involve some type of engagement with natural environments. Some works appear in art galleries, but most appear in the land.

Stephanie Ross’s categories of Environmental Art

Stephanie Ross categorises environmental art in some interesting and useful ways, ways which also help to delineate cases where humans have more or less of a role in the art, and hence categories which suggest how we might approach environmental art in each different context. Ross's categories: masculine gestures; ephemeral gestures; performance works; landscapes and proto-gardens.

1. Masculine gestures (representative artists: Robert Smithson, Michael Heizer, Nancy Holt)

Fairly permanent, and range from earthworks that involve moving tons of earth or rock to softer gestures that are less disruptive to the land.

Strong gestures: Smithson’s and Heizer’s works are overtly human and intentional in terms of using nature for art’s sake. Smithson’s earthworks usually make use of forms on a grand scale – jetties, ramps or mounds which stand out in the environment and mark the land through their sheer mass. Heizer’s works cut monumental forms into earth or rock on a grand scale.

Site specific: The sites chosen by both artists tend to be remote and inaccessible, spaces vast enough for massive art works. Their sites are ‘site-specific’ in that the art work is created in some relation to the chosen site, but the art work is the focal point, with the site mainly as backdrop. This is especially true for Heizer whose forms require a background of seemingly endless space, such as a desert.

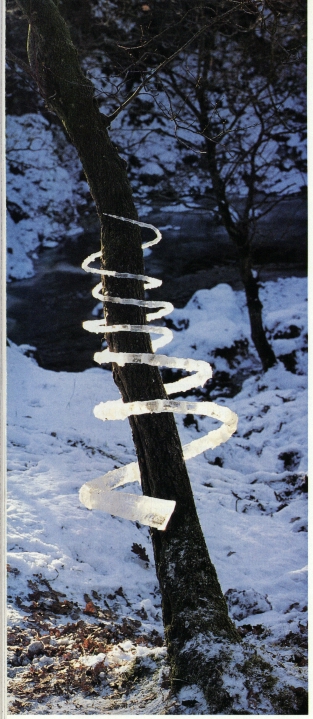

2. Ephemeral gestures (Richard Long, Andy Goldsworthy, Michael

Singer)

The next category, ephemeral gestures, includes works by environmental

artists

such as Richard Long and Andy Goldsworthy.

These art works are:

site-conditioned; impermanent

The materials used are usually gathered from the site itself and incorporated into the setting. Some last for a few moments – a formation of leaves blown away by the wind; some a few hours – an icicle formed onto rocks melts in the afternoon sun; and others for longer – a path tracked through a field.

intentionally sensitive

These works are importantly related to their natural surroundings; indeed, they evolve so much from their surroundings that one might confuse the artefact for nature itself. The sensitivity to nature and veneration of it implicit in these artworks encourages the appreciator (usually via a photograph) to appreciate nature more on its terms than the artist’s. The artist’s role is to enable us to become aware of nature’s value by highlighting it in creative and captivating ways.

Andy Goldsworthy

His

works are site-conditioned and impermanent, using materials gathered from

the site itself and incorporated into the setting. Some last for a few

moments – a formation of leaves blown away by the wind; some a few

hours – an icicle formed onto rocks melts in the afternoon sun,

and others for longer periods.

His

works are site-conditioned and impermanent, using materials gathered from

the site itself and incorporated into the setting. Some last for a few

moments – a formation of leaves blown away by the wind; some a few

hours – an icicle formed onto rocks melts in the afternoon sun,

and others for longer periods.

His works are intentionally sensitive to their natural surroundings. Natural materials are arranged in various ways to work with and highlight nature’s processes and its impermanence, as well as other qualities: its complexity, simplicity, delicacy, strength, changeability, varying shapes and textures, and all its dynamic possibilities.

As an artist, he directly interacts with the environments

in which he works: ‘Andy Goldsworthy’s exclusive use of his

body as a tool for his creative activities, such as licking flower petals

to glue them together, is guided by his desire to have intimate bodily

contact, including taste, with the material.’

(Yuriko Saito, ‘Environmental Directions for Aesthetics and the

Arts’ in Arnold Berleant, ed., Environment and the Arts

(Aldershot: Ashgate, 2002), p. 176.)

We are encouraged to become engaged with natural qualities and to find beauty in nature beyond hackneyed or picturesque sights.

Criticism: However, ephemeral gestures can still be said to manipulate nature for an artistic purpose. Rather than constituting a true interaction with nature, these works appropriate nature, and convey its qualities through artistic gestures.

3. Performance works (Christo and Jeanne Claude)

Other environmental art works are temporary in nature, like ephemeral gestures, but they have another distinctive feature – they are somehow performative. In this third category, performative works, Christo and Jeanne Claude's work is the prime example. Christo and his partner are well known for wrapping things - islands, public buildings, and also for using fabric in the landscape.

Christo and Jeanne Claude: ‘Running Fence’

For more images of this and other pieces go to http://christojeanneclaude.net/rf.html

Running Fence used one hundred and sixty-five thousand yards of nylon to create a soft fence through two counties in California.

This piece, like others, drew attention to both the light and sumptuous qualities of its materials and the features of its site. Running Fence internally framed the landscape in which it was built, and in that way brought attention to aesthetic qualities of both the art work and the land. Although this work is temporary, its impact and orientation towards art means that it shares features with masculine gestures.

In terms of its propensity to engender a relationship with nature, it is a step backward from the more sensitive work of Goldsworthy or Long. While Christo’s work might be taken as a tribute to whatever environment it is situated in, its incongruity with the landscape means that the appreciator’s attention is ultimately on the fabric itself, so that nature, here, serves merely as a backdrop for a brilliant kitsch fantasy – e.g. in his ‘Surrounded Islands’

4. Landscapes and proto-gardens (Alan Sonfist, Helen and Newton Harrison, Agnes Denes)

I turn now to Ross’s final category, landscapes and proto-gardens, which includes the work of Alan Sonfist, Helen and Newton Harrison, and Agnes Denes.

Because living and growing materials, cultivated over time, are essential to these art works, these artists are truly interacting with nature.

Their projects necessarily span relatively large amounts of time, and are usually permanent, although very changeable. Denes’ ‘Tree Mountain – A Living Time Capsule’ (in Finland) was conceived and produced over fourteen years and involved planting ten thousand trees.

Alan Sonfist’s ‘Time Landscape’ attempted to re-create a pre-colonial forest in the urban environment of New York City. The ‘work’ enables urban dwellers to experience a stage in the history of the conflict between culture and nature.

The Harrisons have been involved in marine research, examining the natural cycles of crabs in one of their project.

These works range from being site-specific to site-conditioned, but unlike the other categories, landscapes and proto-gardens involve a direct concern for nature on a more global scale, with a stronger interest in ecological ideas than aesthetic qualities (compared to, e.g., Goldsworthy).

For example, Denes’ work embodies the very idea of ecological harmony, aiming to establish a relationship between humans and the natural environment which is based more on nature’s interests than human interests.

Agnes

Denes’s ‘Wheatfield’ was an artwork which involved planting,

nurturing, and harvesting a wheatfield, but it is still clearly an artwork,

trying to make a statement.:

Agnes

Denes’s ‘Wheatfield’ was an artwork which involved planting,

nurturing, and harvesting a wheatfield, but it is still clearly an artwork,

trying to make a statement.:

"Agnes Denes’s Wheatfield is entirely different from the equivalent wheatfield cultivated by a Midwestern farmer. Though both engage in farming practice and provide an agricultural landscape, the latter does not carry the artistic meaning necessarily attributed to the former. So even when the artwork shares a number of important aesthetic characteristics with the environment, an equally significant distinction keeps them separate." (Saito, 2002, p. 182.)

For more on Denes and other artists try this web site http://greenmuseum.org

The social and political statements inherent in these works are more likely to encourage attachments which have at their core a caring or ethical approach to the environment. Importantly, these attachments begin at the level of particularity.

And for some people, these projects provide a unique opportunity to understand natural processes.

In these cases, appreciation of nature is in the foreground, the human role is backgrounded, much like the minimal management of a conservation area.

Environmental Art and Aesthetic Affronts to Nature

Environmental art can be seen to be harmonious with nature or in conflict

with it, as perhaps an affront to nature itself, i.e., humans imposing

our artwork onto nature, which could be seen as a kind of manipulation

of nature.

In considering how much our appreciation of environmental art is shaped by appreciation of art and how much by nature, we might also consider whether or not environmental art brings us closer to nature or distances us from it.

Question

to think about

Question

to think about

Does environmental art engage us with nature in ways which enable us to develop a relationship with it, or does it distance us from nature?

Does environmental art foster the kinds of attachments that support an intimate relationship with nature, or does it impose humanity on nature, manipulate nature or in other ways undermine harmonious attachments to nature?

Environmental art may give us either a direct or mediated experience of nature... which is it? Well, that depends on the type of environmental artwork.

More than any other type of environmental art (except perhaps Christo), Ross's 'masculine gestures' have received criticism from both ethical and aesthetic points of view.

Some have argued that even when the art works are not ecologically damaging, they are nonetheless unethical, representing an affront to nature:

'Perhaps "defile" is too strong a word to characterize most environmental art. Nonetheless, the general way in which environmental artists alter nature’s aesthetic qualities by turning nature into art does seem to support its being an affront to nature. This is illustrated by Heizer’s works such as "Displaced-Replaced Mass" (1969) in which a 52 ton granite boulder is “messed with” by placing it in an excavated depression. It is also evident in works such as Christo’s "Surrounded Islands" and "Valley Curtain" (1971-2), 200,000 square feet of bright orange nylon polymide spanning a Colorado valley, or Oppenheim’s "Branded Hillside" (1969), a “branding” of the land executed by killing the vegetation with hot tar. In such cases nature is “redefined in terms of art” at a cost to its aesthetic qualities such that to speak of an affront, if not a “denigration,” is quite appropriate.'(Carlson, 2000, p. 155)

It could be argued also, for example, that in the way these works impose human forces on to nature, they strengthen the hierarchical dualisms which have led to the oppression of nature (e.g. human/nature, animal/non-human animal, culture/nature).

These artists, by their own admission, are primarily interested in art rather than environmental issues, so that they are open to such criticisms comes as little surprise.

On aesthetic grounds, they may also constitute an affront, because they ‘forcibly assert their artefactuality over against nature’ and work aesthetically against rather than symbiotically with the aesthetic qualities of their surroundings.

In many cases, these artworks represent an aggressive and disruptive relationship with their environments, akin more to power relationships between people than the cooperative harmony of friendships.

Can you think of any points of support for these types of environmental artworks, in contrast to some of the criticisms above? You might like to post your thoughts on this to the discussion site.

Appreciating Agricultural Landscapes

We now turn to another type of cultural landscape in order to reflect on the relationship between humans and nature. Unlike gardens and environmental art, agriculture has no explicit aesthetic aim – this is a utilitarian type of environment. However, as we shall see, aesthetics has a role.

The New Agriculture

Agricultural landscapes are not discussed much in environmental aesthetics, but Allen Carlson has written a striking essay on the subject of, 'Appreciating Agricultural Landscapes'. (Carlson, Aesthetics and the Environment, 2000).

In a comparison of traditional, pastoral farmlands and the new industrial farming, he shows how we may be able to come to aesthetically appreciate the new landscapes, despite the fact that to the 'untrained eye' they appear bland and monotonous with their “large flat uniform fields” and “featureless metal sheds.” (p. 182)

In aesthetic appreciation, we also ought to be able to overcome the dismal social consequences of the decline of rural communities and depopulation that has been caused by agribusiness. Instead, we may be able to develop an eye for the 'breathtaking formal beauty: great checkerboard squares of green and gold, vast rectangles of infinitesimally different shades of gray…' (p. 185)

Carlson is not arguing that industrial agriculture has more aesthetic value than traditional agriculture; his aim is to try to show that positive aesthetic value may be found in the new, aesthetically challenging landscapes. Nonetheless, his case is controversial and not easy to defend, even if one tries to be open-minded.

There may be aesthetic merit in the new agriculture, and perhaps we ought to attempt to change our tastes, but there are good aesthetic (and moral) reasons for favoring traditional methods of farming.

Carlson argues that because agriculture is a functional landscape, its appropriate aesthetic appreciation must take into consideration function and necessity.The aesthetic merit of industrial farmlands is importantly linked to the fact that they function well and are 'extremely necessary' for food production. On an uncritical level, this may be true: there is no question that they produce a great deal of food efficiently.

But if we carefully examine these assumptions, we have to consider the kinds of criticisms that have been raised against industrial farming. Carlson recognizes the harm underlying these landscapes in terms of the pastoral way of life they have superseded, but he does not take sufficient account of the environmental problems associated with them, such as damage from fertilizers and pesticides, erosion, unsustainable use of water resources, the decrease of animal populations from destruction of habitat, etc.

In a nutshell, this type of agriculture does not fulfil its function well because it is unsustainable.

Once we take on board information about the problems in the new agricultural landscapes, the argument for their aesthetic merit weakens.

These landscapes embody a deeply conflicting relationship between humans and nature in the way that human technology is so strongly imposed on nature, especially when compared to more traditional forms of farming. Their aesthetic qualities are connected to and partly generated by practices that harm the environment, for example, the fertilizers and pesticides that keep the fields and their produce unnaturally perfect in appearance, or the gleaming silver sheds that hide chickens and pigs raised in inhumane conditions.

While we may be able to find some positive aesthetic qualities, appreciation remains very difficult if we know what lies behind the qualities we perceive. Given these concerns, not only is it quite challenging, but it is also not in the environment’s interests for us to try to adapt our aesthetic tastes to these new landscapes.

Traditional Agriculture

Although much less efficient in many respects, various kinds of traditional farming are not only sustainable, but they have other beneficial effects, including social ones. For our purposes here, it is more the aesthetic point of view that interests us. The positive aesthetic value of traditional farmlands is quite evident, in their pastoral beauty, variety, their familiar appeal in terms of the kinds of values they represent, but also in the harmonious relationship they represent. A study of this type of landscape can provide us with an understanding of a distinctive human-nature relationship, the aesthetic bases of that relationship and the aesthetic value that comes with it.

Hedge-laying

For contrast with industrial or intensive agricultural practices consider one practice of traditional agriculture in Britain: hedge-laying. In what follows, I suggest that they express a more harmonious relationship between huamns and nature, compared to the scale of imposition on nature that we find in industrial farming. (Some forms of organic farming may also present a useful contrast in this respect.)

Hedgerows are a familiar sight across Britain. They are pleasing to the eye for the patchwork patterns they create across rolling hills and mountainsides, and, up close, for the distinctive textures of woven branches.

Their primary purpose is to enclose and divide the landscape into fields for various purposes, such as raising sheep, but without doubt they have aesthetic qualities as well. In the activity of creating them, we can also discover an interesting relationship between humans and the environment.

Hedgerows involve manipulating plants – hawthorn, blackthorn and holly – not for production but to serve the specific function of a wall. These walls, however, are living. The activity of pleating together bushes or trees at an angle as they grow generates dense growth which is an ideal home for a rich variety of species, sometimes rare, including butterflies and other insects, birds, badgers and other small mammals such as voles, shrews and dormice.

In open fields where there is little woodland or shelter, hedgerows are an important habitat, and in addition, they serve as windbreaks and help to control soil erosion. Besides their wildlife value and landscape/aesthetic value, hedgerows have historic value, for many of them have been continuously managed (at least) since the 18th century. Because intensive farming and development have led to the destruction of hedges across Britain, there are now special incentives for farmers to conserve and restore them.

Hedge-laying requires a special skill. Knowing how to cut back growth and pleat together branches requires, again, an intimate understanding of these plants and their environment. The activity involves knowing how to create a screen without holes, so that for example, sheep may be kept from wandering. Here, too, there is no explicit aesthetic aim, but rather a functional one. However, the activity of hedge-laying and the result have aesthetic value in the delightful textures and variety of branch shapes, leaves, flowers, berries, birds, their songs and fluttering activity, and so on.

The environment that is shaped by the interaction of intentionality and organic processes is quite distinctive, an environment in miniature which concentrates the aesthetic appeal into an area that can be experienced up close and intimately. There is also a sense of fascination that all of this interest exists within a shaped, living thing. This is nature within a humanly fashioned object, and this nature-artifact synthesis is responsible for much of the aesthetic satisfaction we feel.

Reflect on different types of cultural landscapes - environmental artworks, gardens, topiary, parks, agriculture, etc., and consider whether or not they involve harmonious or conflicting relationships between humans and nature. For example, some may want to argue that hedge-laying, although having environmental benefits, involves a kind of manipulation of nature.

An example of topiary from Levens Hall for more images of this topiary garden go to: http://www.levenshall.co.uk/

Emily Brady, October 2003

| Tutor Details | Biblio | Assessment | Resources | discussion |