Away MAVE

The Distance Mode of MA in Values and the Environment at Lancaster University

Block 2: Husserl, Realism, and the Crisis of the Sciences

|![]() Home

Home![]() |

|![]() Aims

and Outcomes

Aims

and Outcomes![]() |

|![]() Module

Description

Module

Description![]() |

|![]() Tutor

Details

Tutor

Details![]() |

|![]() Biblio

Biblio![]() |

|![]() Assessment

Assessment![]() |

|![]() Resources

Resources![]() |

|![]() Discussion

Discussion![]() |

|

| 1 Background comments and context | 2 Husserl’s separation between science and the life-world | ||

| 3 Galileo’s Approach to Science | 3 What is Husserl criticising? | ||

| 5 Galileo and realism | 6 Scientific realism |

Reading tips:

The focus of this second block is Husserl's The Crisis of European

Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology (this is usually abbreviated

to Crisis) and we recommend that you read Part Two, Sections 8-10. This

is quite difficult reading, but an understanding of it is crucial, especially

if we are to evaluate later criticisms of science that use different interpretations

of what is being said by Husserl.

| The extract from Leiss, ch. 6 ‘Science and Nature’ of The Domination of Nature is a useful introduction to the context of Husserl's writing so I recommend you read that first before tackling the primary source. |

Background comments and context

For "European sciences" we can read 'western science',

Husserl is, in the title, pointing to the European origins of the science

that has emerged.

What Husserl identifies as "Galilean physics" is:

1. the historical development of physics between 1600 and 1700 with the work of Galileo as a particularly fitting symbol and

2. all the science that comes after. As Aron Gurwitsch says:

Within the meaning of Husserl's definition, Einsteinian physics, and quantum physics are sciences of the Galilean style. (1974:34)

The extract we are reading, like the whole of Crisis,

is an introduction to, or rather a leading into, phenomenology. In each

part of the book Husserl is not only doing the work of, e.g., describing

the historical process of the mathematization of nature, but also setting

out the project of phenomenology.

From the initial publication of the Logical Investigations in

1900 phenomenology was established as a means, via the criticism of psychologism,

of criticising the ungrounded assumptions in the wider application of

scientific method. By the time of writing Crisis, when Husserl

was in his mid-seventies, the critique had become historically focused.

Not only were the logical problems surrounding the justification of scientific

method being raised, but also the effect of "impure" sciences

on European culture. He says:

The exclusiveness with which the total world-view of modern man, in the second half of the nineteenth century, let itself be determined by the positive sciences and be blinded by the 'prosperity' they produced, meant an indifferent turning-away from the questions which are decisive for a genuine humanity. Merely fact-minded sciences make merely fact-minded people. (Crisis p.6)

What are, for Husserl, the questions of genuine humanity?

As he goes on to argue it is the questions which have a bearing on reason.

Greek philosophy and the philosophy of the Renaissance addressed reason

and thereby the foundational questions concerning humanities' being in

the world. This Husserl sets against the positivist sciences which have

no role for a foundational philosophy and do not recognize its necessity

to inform their own endeavours.

In the German universities of Göttengen and Munich particularly in

the years between 1913 and 1930 this proposal of starting afresh with

the aim of re-awakening the search for certainty found many keen followers.

United under the slogan "Zu den Sachen!" (to the things)

the early phenomenologists sought to apply the method, as set out by Husserl,

to examine phenomena and in so doing to refine the method in preparation

for its reforming task on the sciences and through the sciences on European

culture. Husserl began the book in 1934 when he was in his mid-seventies

and continued with it until his illness in 1937, he died in 1938. The

background of a nation embracing the irrationalism of Nazism must have

given his task a sense of urgency or even desperation.

In identifying a shift in our approach to the world and tying it to the

development of science Husserl could be interpreted as saying that science

wrongly ascribes certain features to nature. This is not the case, he

is not anti-science, but he is drawing attention to a problem. The problem

is striking him from two directions, the state of the world, particularly

the rise of irrationalism in modern youth and a logical problem with the

internal workings of science. He identifies both issues as a loss of meaning

and does think that science should include questions of meaning and not

in some way set questions of meaning outside of what can be valid knowledge.

| I hope that has whet your appetite to now read the recommended section from Husserl. |

Exercise

Exercise

One way of approaching a difficult text is to attempt to summerise it as you read. With something like this I would recommend approximately one sentence per paragraph. Try not to quote directly, but find your own way of putting what you understand him to mean and, if you're really keen, think up examples to demonstrate your understanding.

Having done a thorough reading, which the exercise above helps to prompt, you could go on to pull out the key themes or issues that Husserl is raising here. My attempt is set out below.

Husserl’s key points: the separation between science and the life-world

Husserl is proposing that there is a conceptual separation

taking place between the world in its idealized/mathematized form as understood

by science and the world that we experience in its everyday form.

The historical origin of the separation arises from the kind of conceptualization

that begins in Galileo's science and the fact that Galileo did not question

the roots of his mathematized nature. Husserl accuses Galileo of concealing

the experiential roots of geometry.

Science claims to uncover the mathematical structure of the 'real world'

existing behind the shifting world of appearances. The idealized form,

due to its nature and due to the obscuring of its origins (in the lifeworld),

has taken on an ontological pre-eminence. That is, it claims to be more

real, fundamental, objective etc. than the lifeworld.

Because the lifeworld, the world of everyday experience, both historically

and for us all from moment to moment precedes the mathematized world of

science the mathematical structures we find in the world are not revealed

in the sense of disclosing the reality behind the appearance. In a very

real sense they are an acheivement of consciousness. (NB this does not

mean they are constructed by us).

The primacy of the life-world does not mean that it is more 'real' than

mathematized nature, for Husserl both have to be bracketed with regard

to existence outside of consciousness and explored phenomenologically

to reveal the invarient structures. (This is not clear from the sections

that you have, but emerges from trying to fit what he says here to a wider

reading).

Husserl is proposing that there is a conceptual separation taking place

between the world in its idealized/mathematized form as understood by

science and the world that we experience in its everyday form.

The historical origin of the separation arises from the kind of conceptualization

that begins in Galileo's science and the fact that Galileo did not question

the roots of his mathematized nature. Husserl accuses Galileo of concealing

the experiential roots of geometry.

Science claims to uncover the mathematical structure of the 'real world'

existing behind the shifting world of appearances. The idealized form,

due to its nature and due to the obscuring of its origins (in the lifeworld),

has taken on an ontological pre-eminence. That is, it claims to be more

real, fundamental, objective etc. than the lifeworld.

Because the lifeworld, the world of everyday experience, both historically

and for us all from moment to moment precedes the mathematized world of

science the mathematical structures we find in the world are not revealed

in the sense of disclosing the reality behind the appearance. In a very

real sense they are an acheivement of consciousness. (NB this does not

mean they are constructed by us).

The primacy of the life-world does not mean that it is more 'real' than

mathematized nature, for Husserl both have to be bracketed with regard

to existence outside of consciousness and explored phenomenologically

to reveal the invarient structures. (This is not clear from the sections

that you have, but emerges from trying to fit what he says here to a wider

reading).

Those

are some of the points that jump out at me from the text, but what did

you get? If asked to express in a nutshell what Husserl is getting at

what would you say? Send your interpretations in to the discussion site.

Those

are some of the points that jump out at me from the text, but what did

you get? If asked to express in a nutshell what Husserl is getting at

what would you say? Send your interpretations in to the discussion site.

There is a detailed examination of the argument in Crisis below. However, you may feel like a break so I have put in another piece of the historical jigsaw by looking at one aspect of Galileo's approach to science.

Galileo Galilei (1564 - 1642) (same date of birth as Shakespeare

and, perhaps more to the point, a contemporary of Francis Bacon)

His discoveries and opinions opened to us the gate of natural philosophy

universal (Thomas Hobbes 1839: vol. 1, viii)

Although Galileo is thought of as developing a new type of science, e.g.,

the use of practical experiments is rightly emphasised, there is in his

work a commitment to much older ideas. His combining of the old and the

new in an exciting and convincing way did lay the foundation stone of

the physics that was to take off and, to some extent, dictate what science

was to become. Attention to this combination of ideas may help us to untangle

the accusation that here is the root of the crisis identified by Husserl.

If we look at his last book Dialogues Concerning Two New Sciences (1638) the experimental data is not really evident. Galileo did conduct practical experiments and they are important to his results, but to convince the reader of a particular position he proceeds by thought experiment and thus leads the reader to reach the same conclusion through a process of deduction. To paraphrase Barry Gower's useful discussion of this, Galileo would see his role as a scientist - a natural philosopher - as providing proof from first principles. He needs to provide what Aristotle termed "reasoned facts", that is, things that are universal and necessary and an explanation of them. The problem with experimental data alone was that it was too close to mere observation of instances, or describing our beliefs about the world, and often issued in messy or even contradictory results. To get at the principles of things like motion you need frictionless surfaces and the best way to secure those is in the mind. Even though Galileo did carry out experiments, rather than giving the reader a record of the results, he uses them to get us to think through what has happened and why. To do this we are using a mixture of common experience, e.g., about what happens to unsupported heavy objects, and reason. In this way Galileo leads us to know facts about the world which were not known previously and gives them the certainty of deduction.

A fun example of this is the following:

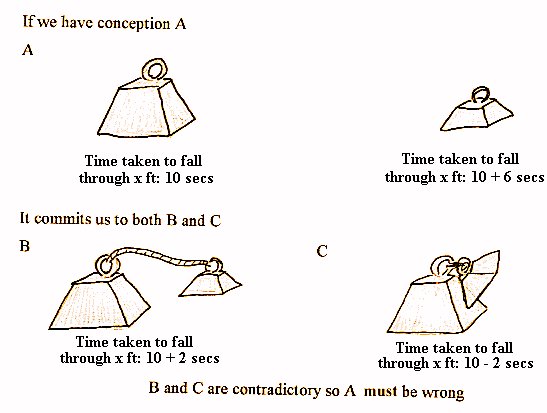

Galileo invites us to consider two objects, one heavy and one light, dropped

from a tower at the same time. He asks which will reach the ground first,

if we hadn't learnt about this at junior school we may well say 'the heavy

one'. So we are asked to think through an experiment. (note: you don't

need a tower or two weights or observers at the bottom). If the heavy

one falls faster, what will happen if you attach the weights to either

end of a piece of string and again drop them simultaneously. If we are

right in our supposition then we now need to think 'will the heavy one

drag the light one along faster than it would travel on its own? And if

it does then surely the light one will also have an effect on the heavy

one and slow it down causing it to travel slower than it would have done

on its own. If that does not already start to sound like a contradiction

Galileo suggests we think of what will happen if the two weights are stuck

together forming one even heavier weight, are we still committed to the

idea that it will now fall faster than when joined with string?

Deepening the analysis: what is Husserl criticising?

1. Husserl is not a critic of science.

The Crisis of European Sciences section 1: "Is

there, in view of their constant success, really a crisis in the sciences?".

Husserl's answer: for the mathematical, physical and biological sciences

that 'the scientific rigour of all these disciplines, the convincingness

of their theoretical accomplishments, and their enduringly compelling

success are unquestionable'.

Only psychology is excluded.

2. Husserl is not a critic of the enlightenment.

His concern is rather: Why the Enlightenment vision of reason has lost its hold?

The modern man of today, unlike the 'modern' man of the Enlightenment, does not behold in science and in human culture formed by means of science, the self-objectification of human reason or the universal activity mankind has devised for itself in order to make possible a truly satisfying life, an individual and social life of practical reason. The belief that science leads to wisdom - to an actually rational self-cognition and cognition of the world and God, and, by means of such cognition, to a life somehow to be shaped closer to perfection, a life truly worth living, a life of 'happiness', contentment, wellbeing or the like - this great belief, once the substitute for religious belief, has (at least in wide circles) lost its force. Thus men live entirely in a world that has become unintelligible.' (Husserl The Formal and Transcendental Logic, Introduction)

3. Husserl is a critic of scientism: i.e. the view that only the positive sciences can provide us with knowledge.

He rejects the restriction of science (in the wide sense of the rational inquiry) to technical issues, and the exclusion of philosophy in particular from the realm of knowledge or science (in a wide sense) - the 'positivistic reduction of the idea of science". In particular, he rejects the elimination of value issues from the realm of rational inquiry:

It was not always the case that science understood its demand for rigorously grounded truth in the sense of that sort of objectivity that animates our positive sciences . . . The specifically human questions were not always banned from the realm of science; their intrinsic relation to all the sciences - even to those of which man is not a subject matter such as natural science - was not left unconsidered. (Crisis)

4. Husserl is a critic of Galilean realism

Husserl traces the problems in 3 back to Galileo's realism.

Galileo and realism

1. What is real and what is not?

for Galileo this is clear as he says:

Now, whenever I conceive of any material or corporal substance, I am necessarily constrained to conceive of that substance as bounded and as possessing this or that shape, as large or small in relationship to some other body, as in this or that place during this or that time, as in motion or at rest, as in contact or not in contact with some other body, as being one, many, or few - and by no stretch of the imagination can I conceive of any corporal body apart from these conditions. But I do not at all feel myself compelled to conceive of bodies as necessarily conjoined with such further conditions as being red or white, bitter or sweet, having sound or being mute, or possessing a pleasant or unpleasant fragrance. On the contrary, were they not escorted by our physical senses, perhaps neither reason for understanding would ever, by themselves, arrive at such notions. I think, therefore, that these tastes, odours, colours etc., so far as their objective existence is concerned, are nothing but mere names for something which resides exclusively in our sensitive body, so that if the perceiving creatures were removed, all of these qualities would be annihilated and abolished from existence. But just because we have given special names to these qualities, different from the names we have given to the primary and real properties, we are tempted into believing that the former really and truly exist as well as the latter. (Galileo The Assayer)

Galileo makes two claims in this passage

G1. The primary qualities of objects (described in the

physical sciences) - shape, position in space and time, velocity, etc.

- are 'real properties' that have objective qualities.

G2. The 'specific' sense qualities of objects, the 'secondary' qualities

- colour, tastes, smells - are not 'real properties' of objects that have

'objective existence', but rather 'reside exclusively in us'.

N.B. Those two claims are logically independent.

2. G1 and G2 might appear to entail a kind of scientism

If only the concepts of the sciences refer to real properties

about objects, then only scientific propositions are candidates as statements

that could be true or false about the world.

Other concepts that describe colours etc. do not refer to properties of

objects and hence cannot be true or false.

Similar claims are made about value-statements:

'Vice and virtue ... may be compared to sounds, heat and cold, which, according to modern philosophy, are not qualities in objects, but perceptions in the mind ...' (Hume A Treatise of Human Nature Book III, 1)

3. Husserl rejects G1 and G2

Galileo is responsible for

...the surreptitious substitution of the mathematically substructured world of idealities for the only real world, the one that is actually given through perception, that is ever experienced and experienceable - our everyday life-world. This substitution was promptly passed on to his successors, the physicists of all succeeding centuries. (Crisis)

Here Husserl is making two points:

H1: the mathematical concepts of the physical sciences describe a 'world

of idealities' - they do not describe the real world. Husserl rejects

G1

H2: the only real world is that we experience - of colour, sound, etc.

Husserl rejects G2.

4. John O'Neil's take on this (open to criticism!)

Husserl's arguments for H1 and against G1 fail.

G1 is true (i.e. scientific realism is true) and hence H2 is false.

But Husserl is right to reject G2?

The problem with Husserl and much subsequent discussion

(eg. H. Putnam, W. Sellars) is they assume that G1 and G2 are related

- that if you are a scientific realist you are a life-world irrealist.

But it is consistent to be realist about both science and the 'life-world'

. Moreover, that is the correct position.

Husserl's case against G1 (The primary qualities of objects (described

in the physical sciences) - shape, position in space and time, velocity,

etc. - are 'real properties' that have objective qualities.)

1. Vs Galilean realism - that the sciences provide a description

of a mathematically structured reality - 'the book of nature is written

in the language of mathematics' for Galileo the language of geometry.

Husserl: examination of the origin of the concepts of mathematical physics

in the life-world, in the practices of measurement and prediction, show

that these concepts are idealizations that serve to improve these practices,

and are not to be regarded as descriptions of a hidden reality.

2. The origins of geometry:

a. The pure shapes that form the objects of theoretical

geometry are absent from the life-world. Experienced shapes have none

of the exactness of the shapes posited in theoretical geometry.

b. What then is the origin of these pure shapes?

The shapes of pure geometry are limit shapes formed in this process of

perfecting the exactness of measurement. They are limit shapes that develop

from the practices of measurement and surveying. 'The art of measuring

is in itself the art of pushing exactness of measuring further and further

in the direction of growing perfection.'

Through the positing of ideal shapes - circles with all points equidistant

from a single point, triangles with angles summing to 180", etc.

- the practical interest in measurement gives rise to an ideal world of

'limit shapes' that form the objects of a purely theoretical science of

geometry.

c. These methods are extended when experienced causal relations between

the ordinary bodies given in the life-world is described in terms of functional

relations between ideal bodies. e.g. the physical laws describing acceleration

in the fall of ideal bodies.

d. However, one can apply these methods to objects and properties only

in so far as they can be directly subjected to practical measurement.

They cannot be extended directly to the 'specific' sense qualities of

objects - colour, warmth, etc. While there exist gradations of light and

dark, warmth and cold, roughness and smoothness, there are neither standards

of measurement, nor the possibility of exactness in the measurement of

gradation. Hence there can be no direct use of mathematical concepts to

specify causal relations between such qualities and others, to predict

warmth, colour and so on.

e. Galileo's hypothesis of an ideal world of shapes correlated with the

sensory-qualities of objects, brings these qualities into the realm of

the predictable - world of atomic particles corresponding to colours,

sounds, heat etc.

In so far as this assists prediction it is fine.

f. The problem lies in the way that Galileo objectifies or reifies these

ideal shapes - treats them as if they were real and substitutes this ideal

world for the only real world - see quote II.3

He treats as real ' what is actually a method - a method which is designed

for the purpose of progressively improving, in infinitum, through scientific

prediction, those rough predictions which are the only ones originally

possible within the sphere of what is actually experienced and experienceable

in the life world.'

Scientific realism

G1. = The primary qualities of objects described in the

physical sciences - shape, position in space and time, velocity, etc.

- are 'real properties' that have objective qualities.

G2.= The 'secondary' qualities - colour, tastes, smells - are not 'real

properties' of objects that have 'objective existence', but rather 'reside

exclusively in us'.

Now we should consider realism in more depth.

I. Is scientific realism true? (G1)

1. Realism vs instrumentalism

Realism (increasing disagreement about what it means!)

'The cognitive status of scientific theories':

Theory realism: The realist holds that the statements in scientific theories

are descriptions of states of the world and like other fact stating assertions,

true or false in virtue of how the world is independently of ourselves.

Instrumentalism: Scientific theories are instruments for making predictions

about observable states of affair.

2. Motivations for instrumentalism:

a. To defend non-science from science - to put science in its place and

undermine special authority for its claims about the nature of reality:

Husserl - to defend the reality of the lived world against Galilean realism

Duhem - to defend theology against science (See Bellarmino against Galileo/Osiander's

preface to Copernicus)

b. To defend science from non-science: to keep science clean of metaphysics

by tying it to what is observable (some of radical empiricists in the

Vienna circle)

3. Motivations for realism:

a. To defend 'the tradition of critical discussion...in the interests

of the search for the truth' (Popper 'Three Views...) See discussion of

the enlightenment

4 . Some arguments against realism

a. Empiricist: our ontology - our beliefs about what exists - should be

limited to that for which we have empirical evidence. We have no good

grounds for any beliefs about theoretical entities which are unobservable

- beyond observation.

b. The use by scientists of models which are not intended to depict real

states of affairs

i. the use of idealisation - perfectly spherical bodies rolling down frictionless

surfaces.

ii. the use of theories eg. Newton's for predictive purposes eg. when

launching rockets to the moon - which could not be regarded as true.

c. The rejection of the account of 'truth' the realist has to assume i.e.

that theories are true or false in virtue of how the world is.

i. pragmatist: a true theory is one that works for the sake of prediction

ii. consensus: truth is just that which an ideal scientific community

would agree upon

iii. constructivist/relativist: what is true depends upon the perspective

of the agent/culture/theory. [I'll return to this later in the term -

is central to much sociology of knowledge]

5. Replies to those arguments:

a.

i. the boundaries of what is and is not observable are shifting.

ii. we can and do make sound inferences from what can be seen to what

cannot.

iii. we can have good reasons for holding that one theory is better than

another and these are good reasons for provisionally believing a theory

to be true

(see Van Frassen for a response to these claims)

iv. it is a fallacy to take what is real to be determined by what we can

experience.

b. the realist can allow that some 'instrumentally useful' theories are

not literally true descriptions of the world, while allowing that others

are not. Indeed the realist can make that distinction whereas the instrumentalist

cannot.

c.

i: need to distinguish what is a test for a true theory from what it means

to say that a theory is true.

ii. Euthyphro problem

'Is that which is good loved by the gods because it is good, or is it good because it is loved by the goods' (Plato Euthyphro 10)

Is that believed by the ideal scientific community, (i)

believed because it is true or (ii) true because it is believed?

The true theory cannot be simply defined as that which ideally competent

scientists prefer. Competence relies on the idea of getting something

right.

iii. This is not just a conflation of 'x is true' with 'A believes x is

true'. Will return to this in a later week.

6. Other positions:

a. Entity realism - Some of the 'theoretical entities' referred to in

science are real. [Of electrons: if you can spray them they are real.

(Hacking)]

b. The debate between realism and anti-realism is a mistake (Fine, Nagel)

II. Are 'secondary' qualities unreal? (G2)

A. Are tables solid?

I have settled down to the task of writing these lectures and have drawn up my chairs to my two tables. Two tables! Yes; there are duplicates of every object about me - two tables, two chairs, two pens...One of them has been familiar to me from my earliest years...It has extension; it is coloured; above all it is substantial...Table No. 2 is my scientific table....My scientific table is mostly emptiness. Sparsely scattered in that emptiness are numerous electric charges rushing about with great speed; but their combined bulk amounts to less than a billionth of the bulk of the table itself. Notwithstanding it strange construction it turns out to be an entirely efficient table. It supports my writing paper as satisfactorily as table No. 1; for when I lay the paper on it the little electrical particles with their headlong speed keep on hitting the underside, so that the paper is maintained in shuttlecock fashion at a nearly steady level...I need not tell you that modern physics has by delicate test and remorseless logic assured me that my second scientific table is the only one that is really there...[A. Eddington The Nature of the Physical World (London: Dent, 1935) pp.5-8]

Restated thus by recent constructivists:

Physicists might wish to point out that, at a certain level of analysis, there is nothing "solid" there, down at the (most basic?) levels of particles, strings and the contested organization of subatomic space. It solidity is, then, ineluctably, a perceptual category, a matter of what tables seem to be like to us, in the scale of human perception and bodily action. (Ashmore, Edwards and Potter, (1994) 'Death and Furniture: the Rhetoric, Politics and Theology of Bottom Line Arguments against Relativism' History of the Human Sciences [7])

Two points:

1. The explanation of the solidity of tables in terms of their being substantial

all the way down is false.

2. All there really is there is the table of emptiness and electronic

charges described by science.

1. is true.

2. does not follow.

Against 2:

There is only one table not two. Eddington's choice is no choice at all.

We need to make no choice between the two descriptions. If a physical

theory entailed that tables weren't solid, then so much the worse for

the physical theory. To say an object is solid is to make a set of claims

about its powers amongst which is its power to resist other objects like

fists. If a physical theory entailed that tables lacked those powers,

then the theory is false. However, fortunately modern physics does not.

What the theory does is to attempt to explain why solid objects have those

powers. In doing so it might refer to entities that make it up which do

not themselves have the property of solidity. But that is not paradoxical

nor gives us reason to doubt the solidity of tables, anymore than the

fact that H2O molecules are not liquid should give us reason to doubt

that water at room temperature is a liquid.

Moral: To explain is not to explain away: to explain a fact 1 (an object

is solid) in terms of another fact 2 (the object has such and such atomic

constitution) is not to explain away the fact 1.

B. Are objects coloured?

Take...colour in the familiar world and its counterpart electromagnetic wave-length in the scientific world. Here we have little hesitation in describing the waves as objective and the colours as subjective. The wave is the reality...the colour is mere mind-spinning. The beautiful hues which flood our consciousness under stimulation of the waves have no relevance to the objective reality...[A. Eddington The Nature of the Physical World (London: Dent, 1935) pp.99-100]

And if at any time I speak of Light and Rays as coloured or endued with Colours, I would be understood to speak not philosophically and properly, but grossly, and accordingly to such conceptions as vulgar People is see all these experiments would be apt to frame. For the Rays to speak properly are not coloured. In them there is nothing else but a certain Power and Disposition to stir up a Sensation of this or that Colour...Colours in the object are nothing but a Disposition to reflect this or that sort of Rays more copiously than the Rest; in the Rays they are nothing but their Dispositions to propagate this or that Motion into the Sensorium and in the Sensorium they are Sensations of those Motion under the Forms of Colours. (I. Newton Opticks Book I, Pt II 1932 edn. pp. 124-5)

Are these arguments sound?

1. To explain is not to explain away: to explain a fact

(that an object has a certain colour) in terms of another fact (the object

has the disposition to reflect such and such a wave-length) is not to

explain away the fact.

In defence of the vulgar against the physicist: Some fallacious arguments

for the non-existence of colours.

2. An object is this or that colour if and only if it has

the power to reflect light rays of a certain wavelength; so objects are

not coloured.

Response: The argument is invalid: 'P if and only Q; so not P' is not

a valid argument form. If the conclusion were true it would follow that

no objects have the power to reflect light rays. [P if and only Q; not

P; therefore no Q] (To explain is not to explain away.)

3. The experience of colour or 'Sensation of this or that

Colour' is subjective/only in the mind. So colour is subjective/only in

the mind.

Response: This assumes that an experience of x is identical with x. This

is false. Compare the following bad arguments: Our experience of the size

of objects is subjective; so the size of objects is subjective. My experience

of students is only in the mind, so students are only in the mind.

4. A physical object has a colour if and only if it has

the power to produce in normal conditions to a standard observer certain

sorts of experience (experience of that colour). So physical objects have

no colour.

Response: see 2.

5. Remember the Galileo extract from The Assayer.

i.e. I can't conceive of a body without shape and size. I can conceive

of an object without colour. So objects have no colour.

Response: What is not real is not determined by what it is possible to

conceive is not real.

Compare: I can't conceive of the universe without matter; I can conceive

of the universe without people. Therefore matter exists and people don't

exist.

6. A physical object has a colour if and only if, if a

normal human observer in normal conditions were to observe the object

she would have certain sorts of experience (experience of that colour).

So if there were no observers then physical objects would have no colours.

Response: Is the argument valid? The argument form 'P if and only if (if

Q then R); so if not Q then not P' is not valid.

C. Two final observations:

1. 'Wretched mind, after taking your evidence from us do

you throw us down? Throwing us down is a fall for you!' (Democritus, fragment

125 R. McKerahan Philosophy before Socrates p.337)

If physics explained away what we experience, what grounds do we have

to believe physical theory?

2. When Newton describes the spectrum of colours that appears on a screen after white light is shone through a prism, or a chemist refers to the shift in the colours of litmus paper, they are not doing psychology. They are describing the screen and the litmus paper, NOT individuals' minds.

III. Conclusion:

1. To explain is to explain.

When, for example, it is claimed that objects have a particular colour

in virtue of reflecting light waves of a particular wave length one is

not explaining an unreal property of an object (possessing a particular

colour) by reference to a real one (reflecting a particular wavelength)

or predicating a real property (possessing a colour) by reference to a

fiction (reflecting a particular wavelength): one is explaining why the

object has one real property - a particular colour - in terms of another

real property - its reflecting a wavelength of a particular frequency.

Postscript: (following Mave discussion from a previous year)

Bad arguments for realism:

Realism is not an explanatory hypothesis - it is a claim

about the status of scientific knowledge and our grounds for having beliefs

about the unobservable.

One argument that is offered for realism is the miracle argument. If science

did not describe the world then how does one explain its success in making

predictions about the observable world. We explain that it is successful

by showing that it describes the world as it is. The argument fails for

a number of reasons:

1. What is supposed to show that the putative realist explanation is true? What evidence could there be for the claim? Are we supposed to have a series of successful theories and then independent grounds for their describing reality? Indeed if we think in that way the only evidence we have goes the other way. Hence the second point.

2. There are plenty of false theories that are successful in making predictions (see Lauden). The response to this point - that theories are approaching truth - begs the question against the instrumentalist, for all that approaching the truth means here is 'makes increasingly good predictions'; the assumptions can change in radical ways.

3. The putative realist explanation is idle. The scientific theory offers an explanation, we don't require a second explanation - that the theory is true - to explain the success of the theoretical explanation. (And would we need a third explanation to explain the success of realism as an explanation of the success of theories?)

The relationship between observations and theories that

refer to unobservables is not an explanatory one. It is evidential. That

a theory gives us good predictions about the observable outcomes of experiments

is as good a reason we could have for believing the theory to be true

is that it, that it makes false predictions is a good reason for believing

that it is false.

The point also has significance for the sociology of science for it makes

realism sound as if it is an explanatory hypothesis competing with others.

I.E. The sociologist claims that the explanation of convergence is a series

of social facts about the agent. The realist claims that the reason for

convergence is that the world is as the theory says it is. That hypothesis

is idle. However reference to facts about the world are not. The reason

why the experiments failed is that the mussels didn't attach themselves

to the nets - not that the mussels engaged in resistance, or that the

hypothesis about mussels was false. It's not the falsity of the hypothesis

that explains the failure of the experiments - its the behaviour of the

animals in question.

Further Reading ( * = especially recommended)

* E. Husserl, The Crisis of European Sciences part 1, sections 1-7. This helpfully sets the stage for Husserl’s more detailed account of the rise of modern mathematical stage. Husserl concentrates in these opening sections on the problem of a loss of ‘meaning’ in a modern culture dominated by science.

A. Gurswitsch, ‘Comment on the Paper by Herbert Marcuse’, in Boston Studies in the Philosophy of Science vol 2 (1965). A response to Marcuse’s interpretation of Husserl as listed below.

M. Hammond, J. Howarth and R. Keat, Understanding Phenomenology (Oxford: Blackwell, 1991). See the ‘Introduction’, esp. sections 1 and 3, and ch. 6, sections 1 and 2. Very clear and helpful exposition, including on phenomenology as a broader philosophical movement and on the background to Husserl’s Crisis.

E. Husserl, ‘Philosophy and the Crisis of European Man’. Lecture given in Vienna 1935 (the so-called ‘Vienna Lecture’); it introduces the themes to be developed in the first part of the Crisis. Available online at: http://www.users.cloud9.net/~bradmcc/husserl_philcrisis.html

* W. Leiss, ch. 6 ‘Science and Nature’ of The Domination of Nature. An excellent summary of Husserl – it will make his argument much clearer.

H. Marcuse, ‘On Science and Phenomenology’, in Boston Studies in the Philosophy of Science vol 2 (1965). Marcuse’s reading of Husserl not only sheds some light on Husserl (although as an interpretation it is controversial), but also helps to illuminate the origins of Marcuse’s own later critique of science.

D. Moran, Introduction to Phenomenology (London: Routledge, 2000), pp. 179-191 of ch. 5 deals with the Crisis.

Supplementary reading to follow up strands that interest you of for essays

Galileo and Realism

Galileo Dialogues Concerning The Two Chief World Systems trans.

Drake, S. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1953

Galileo 'The Assayer' in S. Drake Discoveries and Opinions of Galileo

Popper, K. 'Three Views of Human Knowledge' in Conjectures and Refutations

Hempel, C. Philosophy of Natural Science ch.6

Gower, B. Scientific Method ch. 2 London: Routledge, 1997