Do novels need authors?

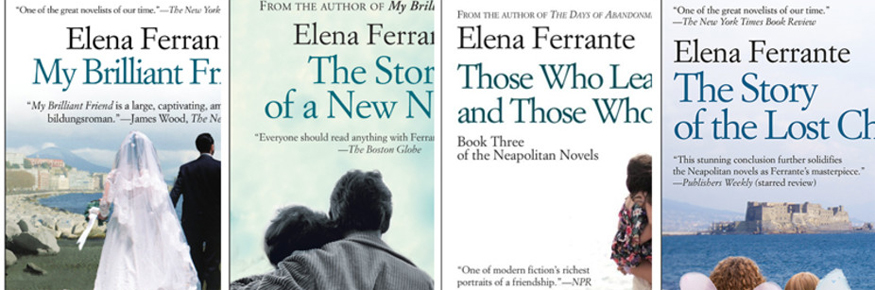

A storm broke out this week around journalist Claudio Gatti’s decision to reveal the true identity of popular Italian novelist Elena Ferrante in an article published across English, French, German and Italian media. Gatti justified rifling through Ferrante’s publisher’s accounts to piece together his sensational story by claiming that the writer’s phenomenal success meant she had relinquished the right to ‘disappear’. The many literary commentators who have since defended her right to retain anonymity argue that the biographical author is entirely irrelevant to the literary text: great works speak for themselves. But the truth about literary authorship lies somewhere in between.

Disappearing acts

Ferrante’s decision to hide her identity bucks western literary celebrity’s calls for constant presence. In so doing, however, she also points to the important ritual disappearances celebrity brings about.

In the west we have come to accept that literary success is marked by talk of spectacular sales figures and how they alter the lives of bestselling authors, how the struggling writer might persevere against the odds, and what the established literary celebrity thinks about global politics. When an author regularly appears not just in the literary pages, but also in the finance, politics and family sections of global newswires, she achieves celebrity status in Sharon Marcus’s definition of the term: someone who brings together diverse publics. As the celebrity author moves in ever broader circles, she becomes ever more present for multiple audiences. But she is also ever less discussed in meaningful literary terms. In fact, often enough the literary author disappears.

Ferrante decided to disappear the other way. In asserting her purely literary persona fronted only by her books, she kept trying to make her celebrity disappear – and how else is one to take her reference to lies and lying, if not in the age-old tradition of vaunting the imaginative possibilities afforded by literature. She refused to be co-opted for other, non-literary purposes. And yet she was anyway. Why?

The simple fact is that texts cannot do without authors, neither when they are written nor when they make their way in the world. This includes anonymous authors. In fact, by drawing attention to their absence, anonymous authors reinforce all the more our innate sense of authorial presence in literature. For, whether or not the biographical identity of the author(s) is known, writing always comes from somewhere. However much literary critics value the intertextual play of language, the reader reads words that she knows have been arranged in that particular order to achieve a certain effect, and this conditions her response. She is inevitably guided by a sense of authorship, and she also actively contributes to it.

Unpicking the Ferrante collective

And here is the nub. It doesn’t matter whether or not we now know who the biographical Ferrante is, because authorship is always anything but singular. That is not the same as claiming, as many now are, that the text doesn’t need its author to carry literary value. The sense of an author is central. The ‘Ferrante collective’ of possible identities that has emerged in the media over the past couple of years has in fact made this beautifully self-evident.

For, however he or she consciously positions herself in the literary sector, the biographical author rapidly begins to multiply. She is already subject to innumerable influences before she even sets pen to paper. This makes the issues of originality and ‘true identity’ thorny. Things only become even stickier as soon as other people in the publishing chain are involved: the copy-editor who normalises the script, the marketing department who visually conveys what the book is about, the reviewers who add their interpretations. Never mind the translators, who set about recreating the whole thing in different languages, accompanied by new editors, rights teams and sales departments, all of whom are speaking to new readers in new cultural contexts. Each time another person in the chain becomes involved, the text’s authorship is modified or expanded that little bit more.

In fact, by not standing in front of her work as a celebrated individual, Ferrante has made room for the true dimensions of literary authorship to be seen. It is always inherently collective, and it is evolving all the time.

This multiplicity of authorship is what makes the limitations of a factual autobiographical reading so unsatisfactory when applied to any literary work. If we pin everything directly back to the one individual carrying Ferrante’s name, we lose the input of everybody and everything else that also becomes enmeshed within the text and variously apprehended as part of it. As they stand on different bookshelves, display different covers, travel on different subway systems and lie on different coffee tables, Ferrante’s novels in American English have already been written by a different ‘Ferrante’ than their Italian counterparts. The Naples that is conveyed to German readers will be much influenced by their translator’s subjective sense of what it might mean to forge a writing identity in post-war, post-fascist Italy. And in fifty years time, ‘Ferrante’s’ authorship will probably mean something quite different to Italian high school children than it does to today’s media commentators. All of these literary manifestations of ‘Ferrante’ convey an author by that name, and they are all different.

Seeing the bigger picture

Ferrante’s novels do not speak for themselves. As it happens, the story they tell of Lenù Greco explicitly invites the reader to experience what it means to take on an identity and to become a writer. And her readers have been Ferrante’s best spokespersons. But in this, her writing is only explicitly exemplary for what all good fiction does anyway. Anyone who picks up Ferrante’s (or George RR Martin’s or Margaret Atwood’s) work picks up, modifies, and appropriates her authorship, so that they too are now part of the authorial chain. This is why novels matter so much to their readers and promoters. The real person is both absolutely peripheral and absolutely central to this process. Ferrante brings the paradox to a point: it is only when the individual writer is spectacularly absent that we might actually learn how to see her importance for literature’s bigger picture.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed by our bloggers and those providing comments are personal, and may not necessarily reflect the opinions of Lancaster University. Responsibility for the accuracy of any of the information contained within blog posts belongs to the blogger.