When travelling north from Lancaster station, I always try to sit on the left side of the train. I don’t do this out of superstition, but because the left, or west-facing, side of the train affords the best view of two sites I’m always pleased to see.

The first of these is the River Lune, sluggish and mud-swollen, as it wends its way towards Sunderland Point and the Irish Sea. The second, which comes into view just beyond Bare Lane, is the broad, level expanse of Morecambe Bay—that ‘majestic plain’, as Wordsworth has it, ‘from which the sea has retired.’

The name Morecambe, so I’m told, means ‘sea-crook’ or ‘sea-bend’, and I suppose this goes some ways towards describing the bent arc of the Bay’s foreshore, which winds northward from Fleetwood to Heysham Harbour and round, past the Cartmel and Furness Peninsulas, towards the Isle of Walney. This crooked shape is chiefly caused by the rivers Lune, Kent and Leven, whose estuaries merge here with the waters of the Keer, Wyre and Winster to form one vast littoral plain comprising some 120 square miles of saltmarshes, mudflats and intertidal channels.

The Lancashire poet Edwin Waugh (from whose book I take my title) spoke of this coastline as a scene of rich and varied beauty: a panorama of ‘changeful picturesqueness’ marked by an ‘exquisite variety of form and colour.’ ‘Here,’ writes Waugh, ‘where the ragged selvedge of our mountain district softens into slopes of fertile beauty by the fitful sea, … we flit by many a sylvan nook, and many a country nest, where we should be glad to linger’.

Waugh’s words appeal to me, because I’m fascinated by railways and he was, rather unabashedly, a tourist of the first great railway age. His little book was published in 1860, just three years after the completion of the Ulverstone [sic] & Lancaster Railway; and, in addition to noting each new viaduct and station on the U&L line, it captures something of the optimism and excitement of the early era of British steam. Admittedly, Waugh’s subject is not so much Morecambe Bay itself, but the Bay as seen from the window of a railcar. But to dwell on this is to overlook one of the more intriguing aspects of his book: namely, that it’s also a swansong for an earlier, more adventurous age of trans-Bay travel.

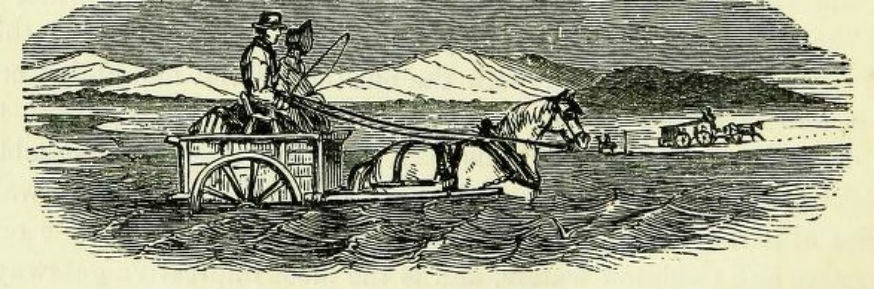

Before the coming of the railway, as Waugh well knew, the most direct line linking Lancaster to the Lake District was the ‘over-sands’ route: a journey of some 20 miles, which involved fording the Kent and Leven estuaries at low tide. From Lancaster, this route ran 3 miles to Hest Bank and then proceeded some 7-9 miles over the mudflats to either Kents Bank or Cart Lane, on the Allithwaite shore. From here, it extended over land to Sandgate, near Flookburgh, whence it cut across the mouth of the Leven to Sandside, near Ulverston. By 1810, a shorter route between Cark and Ulverston Canal Foot was also in regular use. (See a map of the route here.)

In either instance the passage could be treacherous, and not simply because of the Bay’s infamous quicksands and tidal bores. In poor weather, especially on misty evenings, unwary travellers have perished simply because they failed to find their way back to shore. The deaths of the 23 cockle pickers who drowned near Hest Bank ten years ago this month are a grim reminder of a long list of fatalities extending back beyond the 16th century, the era from which the earliest records of over-sands guides (or ‘Carters’) have survived.

Yet, right up to the mid-1800s, the cross-bay route remained a main thoroughfare for travellers who wished to pass swiftly between Lancaster and the Lake District. By 1781, during the great age of picturesque tourism in the Lakes, there was an over-sands coach service running six days a week, promising a ‘sober and careful driver’ and an ‘expeditious’ crossing. Even in the tamer age of Lakeland travel, some sixty years later, the perils of the old route lived on in local memory, inspiring stories such as Elizabeth Gaskell’s ‘Sexton’s Hero’ (1848), a harrowing tale of a young couple’s misadventure on the sands.

My evening commute takes me past the very spot where the climax of Gaskell’s story is set, which is, poignantly, near where those 23 cocklers drowned. And as I look out, like Waugh before me, from the comfort and safety of a railcar, I can’t help but think of all the history that those sands have swallowed up.

Once a busy coach road, today, save for the odd fisherman or dog walker, they seem as boundless and bare as the surface of the moon. Most of my fellow passengers hardly seem to notice them.

What do you think? Share your comments with us below.

Discover more about Lancaster's Department of History.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed by our bloggers and those providing comments are personal, and may not necessarily reflect the opinions of Lancaster University. Responsibility for the accuracy of any of the information contained within blog posts belongs to the blogger.