For such a seminal historical event, Magna Carta is in some respects poorly recorded. We know quite a lot about who the rebel and loyalist barons were and where they came from, and we can reconstruct up to a point their movements in the weeks leading up to the peace treaty that Magna Carta was intended to be. But one of the many things we don’t know is how the barons who forced King John to assent to Magna Carta at Runnymede in June 1215 celebrated when it was all over.

The rebellious barons had been based in London since negotiations with the king had started in May, while John himself had moved around between Reading and Windsor. He dined at Windsor on June 10, with, among others, the newly elected abbot of Bury St Edmunds. He then probably returned to the royal castle after having spent the day at Runnymede in preliminary discussions. The barons were under safe conduct as long as the peace conference at Runnymede that resulted in Magna Carta lasted, but they were camping in royalist-held territory so it probably wasn’t until they returned to London that they could contemplate a feast fitting for the occasion.

London gluttons

Being based in London meant that the widest range of foods should have been available to them. Although government and commerce were not yet as centralised as they were to become, London was already the largest urban centre and the largest market in the country.

A medieval baker with his apprentice.

A medieval baker with his apprentice.

A description of the city by Londoner William FitzStephen during the reign of John’s father Henry II mentions the quantity and variety of food for sale in shops near the river:

You may find food according to the season, dishes of meat, roast, fried and boiled, large and small fish, coarser meats for the poor and more delicate for the rich.

What we know about feasts in noble households at the time of Magna Carta suggests that meat, fish, pies, rissoles and locally grown green vegetables and herbs in thin soup – leeks, chard, parsley, sorrel – would have featured heavily. Feasts were characterised by a proliferation of many dishes served at the same time rather than in “removes” or courses and guests took some of each. Sweet fruit pastries were served at the same time as roast meat.

William FitzStephen also boasted that London was also a magnet for trade: “To this city from every nation under heaven merchants delight to bring their trade by sea.” What may have been self-evident to William was in fact the result of a longer process – the revival over a period beginning in the early 1100s of long-distance trade connecting northern Europe to the Mediterranean and, via Levantine ports such as Alexandria and Acre, to the natural resources of Asia and Africa: silk, cotton, gold, but especially spices. By 1214 there had been over a hundred years of European settlement in the Near East as a result of the Crusades and the Crusader States, and the higher material standards of life in the East were well known in the West.

Spicing up

The revival of trade enabled a food revolution to take place in European kitchens. The wealthy had of course always been able to eat better than the poor, but until the 12th century the differences were largely in quantity and in the ratio of meat to cereals. Trade with the east, however, opened up new kinds of food – imported fruit and vegetables that we now take for granted; spices such as pepper, cumin, cinnamon, saffron and ginger. But importantly, new methods of cooking and new tastes – for those who could afford them – also filtered through.

One of the first European recipe books dates from the end of the 13th century, but probably reflects tastes that had been introduced a couple of generations earlier, around the time of Magna Carta. If today’s food writers were reviewing it they’d probably call it “fusion”. The recipes show how cooking techniques and tastes had been profoundly influenced by eastern Mediterranean practices.

One such is a dish called “Syrian food”, in which a capon is poached with rice flour in a mixture of white wine and almond milk with ginger and another new import, sugar. Syrian food, or Syrian chicken, became a standard of medieval cookery by the 14th century.

This is also found in a slightly different form in the first cookbook in the English language, the Forme of Cury on Inglysch (14th century). The essence of this kind of cooking is the combination of sweet spices or flavours with meat or fish. In the recipe for “luce in soup”, the fish is parboiled whole, then fried in a pan around which raw egg yolk has been rubbed and sugar sprinkled. The fish is served with onions stewed in wine and flavoured with saffron.

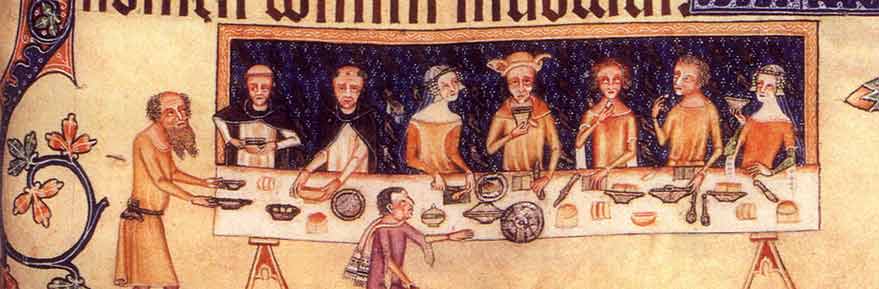

A French ducal feast in 1412.

A French ducal feast in 1412.

Celebrity chefs

Further evidence of the Mediterranean provenance of the recipes in this collection is what may be the first appearance in England of pasta. The word is used to describe a flour-and-egg dough sweetened with sugar and ginger and boiled in strips, then covered with melted cheese. Another new taste revealed in this recipe book is the combination is the use of flowers in food, such as in a recipe for rose-petal soup made with almond milk.

By the late 14th century Europe had its first celebrity chefs, notably the French Guillaume Tirel, whose Le Viandier placed cooking within the wider context of household management.

But at the time of Magna Carta celebrity chefs and such developed tastes for Middle Eastern flavours were a way off. Chefs cooking for the barons celebrating after Runnymede were more likely to have known the Sicilian Book of Cooking, which was heavily inspired by Arabic styles of cooking and spices commonly in use in the Middle East.

So although we can only speculate, the feasting after Magna Carta may well have included some of the first examples of such eastern Mediterranean styles of cooking in England, alongside traditional roast and baked meats.

As to what would they have imbibed – wine, usually watered down, would have flowed at the barons' tables. There is some intriguing evidence to the effect that some English preferred beer to wine, but in the 13th century there were vineyards in many areas of southern England – often planted by monasteries – and wine was also imported in large quantities. At this feast, no doubt, there would have been lots of it.

![]()

Andrew Jotischky is Professor in History at Lancaster University.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed by our bloggers and those providing comments are personal, and may not necessarily reflect the opinions of Lancaster University. Responsibility for the accuracy of any of the information contained within blog posts belongs to the blogger.