|

|

|

Summary: DENNETT DEFENDS THE IDEA THAT WHEN WE EXPLAIN SOMEONE'S BEHAVIOUR IN TERMS OF BELIEF AND DESIRES WE ARE NOT INVOKING INTERNAL STATES. WE ARE INVOKING THEORETICAL CONSTRUCTS WHICH HAVE BEEN ELABORATED BECAUSE OF THEIR EXPLANATORY POWER.

Contents |

So far we have mostly addressed 'the problem of consciousness':

In explaining our own behaviour and the behaviour of others in ordinary life the notion of a belief figures prominently. If we think of the brain as a computer, how are we to think of belief?

|

|

Daniel Dennett, pic courtesy Atlantic Online Dennett's Center for Cognitive Studies webpage |

Our first shot might be this: beliefs are data stored in the brain. Take my belief that my brother is in London. If the brain is a computer, you might suggest, there is a neural circuit somwhere in the grey matter twinkling away, storing this 'thought'. Aquiring this belief was this circuit beginning to twinkle. If it stopped twnking, I would no longer have that belief.

Daniel Dennett sayswe should think of beliefs as constructs - theoretical constructs.

See the paper by Dennett called 'True Believers' in the Reader.

Dennett's starting point is the very important interest he thinks we have in predicting people's behaviour. We are constantly observing what the other people around us are doing and constantly we are interested in predicting what they will do next. This is the stuff of everyday human intercourse.

To help us predict the behaviour of others we have developed it is argued, a theory. We have developed a sort of informal, everyday psychology. It has been called folk psychology. The theory, says Dennett, is a good one - we find that when we use it to try and predict people's behaviour it works.

|

| Folk psychology. Pic courtesy Andel3w |

What is it, this theory?

Its basic terms are belief and desire, belief and want, if you prefer.

Folk psychology explains almost all human behaviour in terms of belief and desire.

"He did this because he wanted such and such and thought doing this would get him it."

That is s sort of explanation schema into which a great deal of everyday explanation of human behaviour fits.

I shall suggest behaviours and you suggest some possible explanations.

Why have I got this key?

Why did I come to campus along the A6 this morning?

Why did the Queen intervene in the Burrell trial?

The pattern is: we believe such and such; we want such and such; this leads us to do such and such.

Prompt: Can anyone think of a piece of human behaviour which we would not ordinarily invoke a belief-desire explanation?

What about this?

This approach to explanation goes along with belief-desire approach to prediction.

What will Charlie do next?

It will depend on what he wants and what he thinks will get him it.

Supposing we know he has missed his lunch. We may guess that he will be hungry. We may think he believes that eating a little something in the lecture will alleviate his hunger. And so we may predict that he will start eating before long.

Will Blair sanction 16%?

What does he want? He wants to avoid spending the whole of the injection of money announced earlier on salaries. He believes that an over-generous offer will set a precedent for rocketing wage bills. Therefore one predicts that he will sanction 16% only if much of it is self-financing.

So here we have folk psychology at work, explaining and then generating predictions of behaviour by ascribing beliefs and desires to people.

You can easily think of this as a sort of mechanical theory. It seems to be saying what brings a particular bit of behaviour about is the occurrence of two things, a particular belief and a particular desire. When these occur together the behaviour is generated.

That way of thinking treats the belief as something that is in place before the behaviour occurs, and it treats desires in the same way. It suggests these are two things which are in place or take place in the brain or in the mind and that they bring about the behaviour.

But Dennett says it needn't be like that.

You don't have to think of a belief as something that is there in the brain - or in the mind - prior to the behaviour.

What is his alternative?

In 'True Believers, he doesn't have one. He is trying to be open-minded. He is saying that the fact that our way of thinking about behaviour in terms of beliefs and desires doesn't show anything about how the brain functions. It is he thinks undoubtedly the brain that is conducting the calculation which produces our prediction as to what a person is going to do next, but he thinks it doesn't follow that in the brain there must be bits of the brain, or circuits in the brain, or networks of activation, corresponding to the beliefs and desires.

He says what we have posited is that predictions based on a belief-desire analysis are quite good. Talk of beliefs and desires gives good predictive power. But we don't have to think of them as existing in the brain or mind of the person behaving. We find that by attributing beliefs (and desires) to a person we can predict their behaviour. But this doesn't mean these things are any kind of episode or state in the mind or brain. They could be 'constructs'.

This success of the belief-desire model means that these concepts have a certain utility. They have proved themselves useful in predicting behaviour. They are instrumental in the task of prediction.

This is how Dennett thinks of the concept of belief: it is useful in a very successful theory we have developed for explaining human behaviour.

Does this means that Dennett thinks beliefs don't actually exist? This is a good question.

Dennett thinks the concept of belief can be useful - instrumental - in prediction without there having to be, corresponding to any belief of mine, a bit of the brain, or a sequence of coding in the brain program, corresponding to that belief.

To say a person has a belief doesn't commit you, according to Dennett, to thinking there is a state of the brain, or state of a bit of the brain, or neural process which is that belief.

We can attribute beliefs to people perfectly soundly without making any assumptions of this kind.

The concepts of belief and desire do their work, play their role in helping us predict behaviour accurately, quite irrespective of what events or what states may or may not be inside the person.

|

| Magnetic lines of force. Animation courtesy NASA |

There is perhaps a parallel with lines of force.

If you take a bar magnet and let iron filings arrange themselves freely they will fall into a certain pattern.

You can predict the pattern by saying: there are lines of force set up by the magnet's poles, and the filings arrange themselves so as to align themselves with these lines.

What are the lines of force?

The line of force is a concept which is instrumental in making the behaviour of the filings predictable.

That is all we need say.

There is not necessarily any event or state or process corresponding to them in the region of the magnet.

The concept doesn't get its sense by referring to any such things.

It is useful.

It proves its usefulness by playing apart in successful prediction.

So with beliefs and desires.

These concepts are instrumental in making successful predictions of human behaviour. But that doesn't mean they refer to real states or real events within the person.

This is the instrumentalist construal of mental states, of beliefs and desires in particular.

Is there a better parallel than lines of force?

Some philosophers have been taking an instrumentalist view of all concepts used in theories where straightforward observation seems to be excluded.

The concept of the atom would then be an example.

Atoms, at some point at any rate, were thought to be unobservable. But they were and are invoked by successful physical theory. The success of that theory did not show, instrumentalists argued, that atoms must exist.

The concept of the atom could and should be regarded as purely instrumental: not referring to entities at all, but just constructed by the theory to make prediction possible.

The atom is sometimes said to be on this account a 'theoretical construct'.

The concept of the electron is another example. It is a mistake to think of electrons being very small Ping-Pong balls, or very small clouds of charge; wrong to think that with sufficient magnification we might be able to see one.

The electron is a construct to help us predict.

Chromosomes, genes, forces, vice-chancellors, have all received this treatment at various times.

These terms, it is said, do not refer to real things that are too small or too remote to be seen.

They are purely conceptual devices to help us explain what happens and predict what will happen next.

|

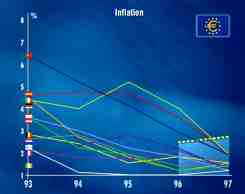

| Inflation. Graph courtesy the European Commission |

Inflation, confidence, public opinion, Mr Takanawa are also vulnerable.

This is Dennett's approach to the question of what a belief is. But it bears back on the problem of consciousness.

It is Dennett's programme to show how beliefs and desires could be regarded as theoretical constructs.

The advantage of this strategy is that it bypasses the traditional impasse that concentrating on consciousness gets us into.

If we understand beliefs etc as conceptual devices playing a possible part in explanation we don't need to bother whether system is conscious or not. The key question becomes: does it display behaviour of such kind and of such complexity that intentional explanations - explanations in terms of belief and desires - are required to explain/predict it.

That is how Dennett's thoughts about what beliefs are fits into his thought about consciousness. He is wanting at least to stop all enquiries about the mind running into the sand of 'consciousness'. Let's think about other things, and maybe when we come back to 'the problem of consciousness' we will discover that it looks different or even that it has been dissolved.

But about belief he thinks this. Human behaviour (and not only human behaviour, displays patterns which the notion of 'belief' (and 'want') latch on to. By thinking of behaviour in terms of beliefs and wants we are able to get a hold of these patterns and at any one time have a good shot at predicting what will happen next. These patterns in our behaviour are objectively there, and objectively they support predictions.

They are patterns which Dennett explains by asking us to think of superphysicist Martians. They are supposed to be able to predict human behaviour, but they do so by understanding the detail of us as physical systems - just as one of our physicists can predict the behaviour of a thermostat by understanding its physics:

Suppose…one of the Martians were to engage in a predicting contest with an Earthling. The Earthling and the Martian observe (and observe each other observing) a particular bit of local physical transaction. From the Earthling's point of view, this is what is observed. The telephone rings in Mrs Gardner's kitchen. She answers, and this is what she says: "Oh, hello dear. You 're coming home early? Within the hour? And bringing the boss to dinner? Pick up a bottle of wine on the way home, then, and drive carefully." On the basis of this observation, our Earthling predicts that a large metallic vehicle with rubber tyres will come to a stop in the drive within one hour, disgorging two human beings one of whom will be holding a paper bag containing a bottle containing an alcoholic fluid. The prediction is a bit risky, perhaps, but a good bet on all counts. The Martian makes the same prediction, but has to avail himself of much more information about an extraordinary number of interactions of which, so far as he can tell, the Earthling is entirely ignorant. For instance, the deceleration of the vehicle at intersection A, five miles from the house, without which there would have been a collision with another vehicle -whose collision course had been laboriously calculated over some hundreds of meters by the Martian. The Earthling's performance would look like magic! How did the Earthling know that the human being who got out of the car and got the bottle in the shop would get back in? The coming true of the Earthling's prediction, after all the vagaries, intersections, and branches in the paths charted by the Martian, would seem to anyone bereft of the intentional strategy as marvelous and inexplicable…There are patterns in human affairs that impose themselves, not quite inexorably but with great vigor, absorbing physical perturbations and variations that might as well be considered random; these are the patterns that we characterize in terms of the belief, desires, and intentions of rational agents."

Daniel Dennett, "True Believers: the intentional strategy", reprinted

in Lycan, Mind and Cognition, 2nd edition, p.81,2.

| Some more of the context from Dennett's True Believers article is here. |

So for Dennett our folk psychology (our belief/desire explanations) reflects the fact that there are patterns in our behaviour, different from (but entirely dependent on) the patterns the physicist studies. We might say they are patterns at a different 'level'.

What he is questioning, in suggesting that beliefs might be constructs, is whether these patterns in our behviour are brought about by structurally similar patterns in our brains. But it is just this, he claims, which is assumed by those who think that if we investigated any particular belief attributed to a person we would find a distinct representation of it somewhere in his or her brain.

There are two theses that we ought to keep apart, he says:

He adds, as a matter of fact:

"There are reasons for believing in the second pattern, but they are not overwhelming."

Daniel Dennett, "True Believers: The Intentional Strategy" reprinted

in Lycan, Mind and Cognition, 2nd Edition, Oxford, 1999, Blackwell, p.85.

He gives what appear to him to be the best reasons here,

casting them as a defence of something called the 'Language of Thought' hypothesis.

This is essentially a pointer forward: we have a go at the issues involved via

an explicit discussion of this hypothesis later.

Revised 27:11:02