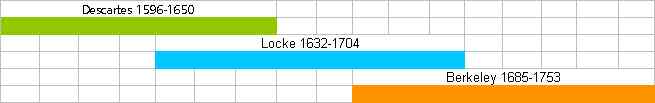

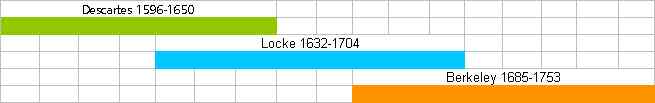

One way of putting Locke's distinction between primary and secondary qualities is to say that some qualities are just 'in the mind.'

In the same loose terms, Berkeley maintained that all qualities were 'in the mind'.

Berkeley did not reject Locke's argumentation in toto. He thought that half of it was on the right lines: the half that said of such and such qualities that they were 'in the mind'. Berkeley just added that the rest were too. He argued that the arguments that Locke thought were enough to show some qualities were 'in the mind' were in fact enough to show that all properties were the same in this regard.

A way of putting this is to say Berkeley rejected the distinction Locke attempted to make between primary and secondary qualities.

Berkeley's gist is to claim that all the arguments Locke uses to show that such and such a quality is secondary apply to all qualities.

|

Some web resources

|

Here are some of the arguments Locke makes in trying to establish the primary/secondary distinction. (This just reprises material from presentation Locke 5.)

|

An Italian Snuff Box, circa 1820

Of micro-mosaic, porphyry and gold. Pic courtesy Adrian Sassoon |

|

| Pic courtesy Black Dog of the Month Archive |

We can imagine a black dog turning grey, but not losing its extension.

A piece of paper can lack smell but not size.

One way of putting the distinction is to say that some qualities exist in objects in the material world, while others exist only in the mind of a perceiver.

Berkeley tries to establish that there is no valid distinction. (He wants this to establish that all qualities exist solely in the mind. He accepts that it can be shown that some qualities can exist only in the mind, and attempts to show that this is true of all qualities.)

1.

'They who assert that figure, motion, and the rest of the primary or original qualities do exist without the mind in unthinking substances, do at the same time acknowledge that colours, sounds, heat, cold, and suchlike secondary qualities, do not - which they tell us are sensations existing in the mind alone, that depend on and are occasioned by the different size, texture, and motion of the minute particles of matter. This they take for an undoubted truth, which they can demonstrate beyond all exception. Now, if it be certain that those original qualities are inseparably united with the other sensible qualities, and not, even in thought, capable of being abstracted from them, it plainly follows that they exist only in the mind. But I desire any one to reflect and try whether he can, by any abstraction of thought, conceive the extension and motion of a body without all other sensible qualities. For my own part, I see evidently that it is not in my power to frame an idea of a body extended and moving, but I must withal give it some colour or other sensible quality which is acknowledged to exist only in the mind. In short, extension, figure, and motion, abstracted from all other qualities, are inconceivable. Where therefore the other sensible qualities are, there must these be also, to wit, in the mind and nowhere else.'

2

'I shall farther add, that, after the same manner as modern philosophers prove certain sensible qualities to have no existence in Matter, or without the mind, the same thing may be likewise proved of all other sensible qualities whatsoever. Thus, for instance, it is said that heat and cold are affections only of the mind, and not at all patterns of real beings, existing in the corporeal substances which excite them, for that the same body which appears cold to one hand seems warm to another. Now, why may we not as well argue that figure and extension are not patterns or resemblances of qualities existing in Matter, because to the same eye at different stations, or eyes of a different texture at the same station, they appear various, and cannot therefore be the images of anything settled and determinate without the mind?

3

'Again, it is proved that sweetness is not really in the sapid thing, because the thing remaining unaltered the sweetness is changed into bitter, as in case of a fever or otherwise vitiated palate. Is it not as reasonable to say that motion is not without the mind, since if the succession of ideas in the mind become swifter, the motion, it is acknowledged, shall appear slower without any alteration in any external object?'

Berkeley's summing up:

'In short, let any one consider those arguments which are thought manifestly to prove that colours and taste exist only in the mind, and he shall find they may with equal force be brought to prove the same thing of extension, figure, and motion. Though it must be confessed this method of arguing does not so much prove that there is no extension or colour in an outward object, as that we do not know by sense which is the true extension or colour of the object. But the arguments foregoing plainly shew it to be impossible that any colour or extension at all, or other sensible quality whatsoever, should exist in an unthinking subject without the mind, or in truth, that there should be any such thing as an outward object.'

(Principles of Human Knowledge, Section 15)

The most celebrated difficulty faced by Berkeley's immaterialism is framed by the question: if a sensible object is an idea (or set of ideas) what becomes of it when it is not being perceived?

Not much, if we are to go by eg the webcam looking at the South Pole.

Berkeley has two rather different shots at this. First he says that what when we say such-and-such exists even though it is not being perceived is that such-and-such perceptions would be got under certain conditions. Berkeley's second answer is that a sensible object often exists in the mind of God when it is not before the mind of one of us.

God can share his ideas with other spirits (minds). This gives a sense in which a sensible object can exist independently of any human mind perceiving it.

|

There was once a young man who said 'God |

Dear Sir, Your astonishment's odd; |

|

Knox |

This doesn't break with Berkeley's celebrated principle that

esse is percipi

to be is to be perceived

In terms of the example of the general idea of a triangle:

| I attempt, with the aid principally of R.I.Aaron's book The Theory of Universals, to give an introduction to the issue of generality here |

Locke says you get a general idea of triangle by abstracting from a plurality of particular ideas of this triangle, that triangle, etc.

Berkeley says: How can there be an idea of a triangle which does not have any particular size? How can there be an idea of a triangle which is neither isosceles, nor equiangular, nor right angle, nor anything in particular at all? How can it be intelligible to propose an idea which is indeterminate in all its properties?

Locke's idea of a general idea is a contradiction in terms.

All our ideas, Berkeley insists, are particular ideas, and have to be such. As far as triangles are concerned, all we can have are ideas of particular triangles.

He

thinks we cannot have an idea of e.g. 'extension' as such - extension on its

own, separated from other ideas such as colour. We can only have an idea of

a particular thing that has extension among many other qualities.

He

thinks we cannot have an idea of e.g. 'extension' as such - extension on its

own, separated from other ideas such as colour. We can only have an idea of

a particular thing that has extension among many other qualities.

(The reply Scruton suggests: Locke was referring, not to a triangle, but to the idea of a triangle; it is ridiculous to suppose that an idea of a triangle is itself a triangle and therefore determinate in shape. (Scruton, Short History, p.99.))

What then is Berkeley's account of generality?

We do not have any general ideas. We have particular ideas which are used in a distinctive way.

When I conduct a proof in geometry about triangles, for example, I conduct it with the use of an idea of a particular triangle. But if the proof doesn't mention the size of the triangle I am using, it applies to all triangles irrespective of size. In this way my particular triangle can be used to stand for others.

The new science thought of itself as investigating the corpuscular understructure of the material world. If the reality (outside the mind) of these corpuscular structures was denied, as it was by Berkeley, what alternative account of science be given?

He thought that science - natural philosophy - could go on much as before, and that it didn't need any assumption about what underlay reality. In particular, it was not in the least dependent on 'on the supposition, that corporeal substance or matter does really exist.' (Principles of Human Knowledge, Section 50).

Natural philosophy is, in Berkeley's view, 'just the study of the uniformities and regularities of our experience.' (Woolhouse, Introduction to Berkeley's Principles of Human Knowledge, p.21.)

Berkeley's immaterialism is sometimes put by saying he rejected any notion of 'substance'.

Berkeley's discussion of 'substance' is a reaction to Locke's, so we have to remind ourselves of what Locke said first.

And we also have to bear in mind a distinction that Descartes made much of: the distinction between properties and the bearers of properties.

One way of encapsulating the Locke - Berkeley disagreement is to say that Berkeley thinks there are only properties, and accuses Locke of thinking that there are bearers of properties as well. It is controversial whether Locke is guilty as charged.

(But - beware - this formulation is oversimplified. Let us try and go into some of the detail.)

Locke's position is that we build all our knowledge and opinion on our sense experience. That is what makes him an empiricist.

But Locke seems to be saying in addition to this that what our sense experience gives us directly is ideas of properties.

If Locke does think this then his position is that all our knowledge and opinion is based on ideas of properties.

Does Locke hold that all our knowledge and opinion is based on ideas of properties?

One thing that gives this impression is Locke's list of simple ideas. It is a list of properties.

In some of the things Locke says this appearance is belied. He sometimes suggests that we get directly through our senses the idea of a tree, for example. - even though elsewhere he painstakingly explains how we get out idea of a tree by adding a special idea - substance - to the ideas of the properties of a tree that we get through our senses (see below).

Even if Locke thinks that sometimes we get an idea of a thing directly through sense experience, it does seem clear that he thinks all experience can be 'analysed' into simple ideas. It seems also true that simple ideas for Locke are exclusively ideas of properties. So we take the following to be the best basis on which to proceed: Locke thinks all knowledge and opinion has to be built up out of ideas of properties.

BUT: we seem ordinarily to think there are bearers of properties as well as properties. A Lockean way of putting this is to say: we apparently have the idea of a bearer of properties. Locke's project is to show how all our ideas are derived from sense, internal or external, either directly or indirectly, so Locke has a problem here.

|

| John Locke. Pic coutesy Brooklyn College |

En route to accounting for knowledge and opinion, Locke has to say how our idea of a bearer of properties (as distinct from a property) can be built out of ideas of properties.

How does he do this? There are two interpretations of what Locke says:

1. The first interpretation is: though we appear to have the idea of a bearer of properties, we don't really. His thesis on this interpretation is that 'things are simply sets of properties'.

We mistakenly think that the idea of a thing consists of something besides the set of ideas of properties.

(It is created, this illusion, Locke is interpreted as suggesting, by the fact that sets of properties go together.)

That is one way of interpreting Locke.

2. The second interpretation is this. Locke is held to maintain that the idea of a thing consists of a set of ideas of properties plus the idea of 'substance'.

What is 'the idea of substance'? It seems to be a thought, the thought namely that the set of ideas of properties it occurs with all inhere in one and the same 'substratum'.

Locke doesn't say anything clearer about this.

Berkeley latches onto the first interpretation. Someone with Locke's empiricist principles, Berkeley objects, is just not entitled to this putative notion of a 'substratum'. The idea of a substratum is the idea of an 'x' with no properties. Berkeley thinks this is not really conceivable - not intelligible.

If we are right to ascribe to Locke the view that all knowledge and opinion is based on ideas of properties, Locke would have to explain how the idea of an x completely lacking in properties could be derived. How can he?

Buzz: is Berkeley right? Is the notion of 'substratum' pointed to here just a confusion?

If you think there is a difficulty with 'substratum', do you think it is just the empiricist who has the difficulty?

Let us be clear: the substratum cannot be the corpuscular constitution of the thing in question.

The corpuscular thesis has no bearing at all on the thesis that properties have to inhere in something.

I.e. if you say: 'properties have to inhere in something' it completely misses the point to say Yes, properties flow from a thing's corpuscular constitution.'

Corpuscles have properties too. They are not candidates for the x in which

properties inhere.

Where does this leave Berkeley? I think the situation is that he starts out

alongside Locke with the thesis that all knowledge and opinion must be built

out of ideas of properties. He cannot make sense of the idea of a substratum.

So he is left with the thought that things are bundles of properties (with no

string).

|

| Bishop Berkeley's memorial, Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford.

Pic courtesy the homepage of Dave Berkeley |

How can we have reason to think there is more than one mind (my own)?

Berkeley accepts that we cannot think of a mind (in my own case) as an idea. There is clearly (he acknowledges) more to my mind than an idea or a bundle of ideas. (It is the thing that perceives ideas.) So he acknowledges two types of existent, minds and ideas.

Having got clear that there was such a thing as a mind, Berkeley seems to rely on the argument (reminding one of Descartes) that a good God, which he thinks must exist, would not have misled us on the key question of whether there were more minds than His/Hers and my own.

| A..To argue that Locke is to be disregarded on account of his prejudice against Christian belief | B. To argue that Locke's arguments purporting to show that some qualities are 'in the mind' only apply in fact to all qualities | ||

| C. To argue that Locke is mistaken on all major points of his philosophy | D. To argue that though most people will inevitably begin by thinking his (Berkeley's) immaterialism is ridiculous, with a little mathematical training anybody could be got to see that it must be true | ||

| A. A windmill looks exactly the same to someone near at hand as it does to someone a long way away - in perception we make the appropriate adjustment in the light of how near we are to the object | B. A windmill looks differently to two different observers just as a bowl of water may feel warm to one and cold to another | ||

| C. Windmills and bowls of water have absolutely nothing to do with each other | D. In giving his argument from the bowl of luke warm water Locke takes a misleading case. Most of the time two people in the same room would be used to the same temperature and the water would feel just the same to both. | ||

|

A. There is no such problem - things actually don't exist when people are not perceiving them |

B. God created enduring objects and would not allow them to pass in and out of existence all the time | ||

| C. What you mean when you say objects exist even when noone is looking at them is that they would be perceived in certain different circumstances, and anyway God is always perceiving them | D. Enduring objects are minds | ||

| A. There aren't any 'general ideas'. | B. General ideas are innate | ||

| C. General ideas are formed by subtracting from a set of particular ideas the elments that the members don't have in common | D. The only truly general ideas are ideas of numbers, and this is why mathematics is so central to knowledge | ||

|

A. Locke is wrong to think that properties inhere in tiny 'corpuscules' or 'atoms'

|

B. All knowledge and opinion must be built out of ideas of things plus ideas of their properties |

||

| C. An empricist is not entitled to the idea of a bearer of properties that does not itself have any properties | D. Descartes' view that there are no individual material things but instead just one single material substance with the appearance of independent material things occurring as votices in the one substance is broadly correct | Ask a friend | |

END

Bowl courtesy Between a Rock and a Hard Place

Almond courtesy Laboratory Specialities

Triangle courtesy The Gay Home Mall