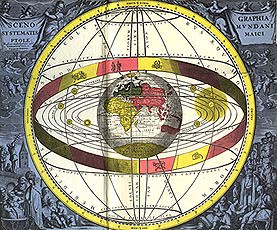

The geocentric world view of Ptolemy according to the star atlas of Andreas Cellarius from 1708 (first print 1661). Courtesy Museon

|

| The geocentric world view of Ptolemy according to the star atlas of Andreas Cellarius from 1708 (first print 1661). Courtesy Museon |

The medievals looked out - or, better, looked in - to a universe that was experienced very differently from the way in which we Moderns experience our own. 'To look out on the night sky with modern eyes is like looking out over a sea that fades away into the mist, or looking about one in a trackless forest - trees forever and no horizon. To look up at the towering medieval universe is much more like looking at a great building.' (C.S. Lewis, The Discarded Image, Cambridge, 1994, CUP, p. 99)

The medieval interest in the Universe was not primarily in its structure however, nor in how it worked, but in what it, and everything that belonged to it, meant . Medieval people located themselves not in a structure they thought of as physical, but within a network of meaning.

Animals and plants, like human beings, belonged to the sublunary region. They were thought of as belonging, to a hierarchy of being, a linear Scale of Nature. Medieval people looked for a different type of explanation for things and happenings than we Moderns: the notion of 'purpose' or 'end' played a much more central role. Natural things were thought of as having a 'nature', and an internal 'drive' to realise it. Reason was the human being's guide in understanding what their nature demanded. The scholastic concepts of 'form' and 'essence', which also played a central role in the understanding of understanding, were philosophical articulations of these ideas.

This world-picture gave way to that of Modern science in a seismic change whose epicentre lay in the 17th Century. A practical concern with natural things was replaced, according to one analysis, with the objective study of nature. In another account, Foucault argues that the essential change was the splitting of language off from the world, which provided the means whereby the world could be ordered, yielding mathesis, the first great project of the Modern épistème.