Conceptualisations of Animals Plants and Nature in the West |

||

|

|

|

|

Module 406Conceptualizations of animals, plants and nature in the WestReason, nature and the human being in the West: an historical approachBlock 1: The medieval period and the emergence of modern science |

Three hundred word summary

The medievals looked out - or, better, looked in - to a universe that was experienced very differently from the way in which we Moderns experience our own. 'To look out on the night sky with modern eyes is like looking out over a sea that fades away into the mist, or looking about one in a trackless forest - trees forever and no horizon. To look up at the towering medieval universe is much more like looking at a great building.' (C.S. Lewis, The Discarded Image, Cambridge, 1994, CUP, p. 99) The medieval interest in the Universe was not primarily in its structure however, nor in how it worked, but in what it, and everything that belonged to it, meant . Medieval people located themselves not in a structure they thought of as physical, but within a network of meaning. Animals and plants, like human beings, belonged to the sublunary region. They were thought of as belonging, to a hierarchy of being, a linear Scale of Nature. Medieval people looked for a different type of explanation for things and happenings than we Moderns: the notion of 'purpose' or 'end' played a much more central role. Natural things were thought of as having a 'nature', and an internal 'drive' to realise it. Reason was the human being's guide in understanding what their nature demanded. The scholastic concepts of 'form' and 'essence', which also played a central role in the understanding of understanding, were philosophical articulations of these ideas. This world-picture gave way to that of Modern science in a seismic change whose epicentre lay in the 17th Century. A practical concern with natural things was replaced, according to one analysis, with the objective study of nature. In another account, Foucault argues that the essential change was the splitting of language off from the world, which provided the means whereby the world could be ordered, yielding mathesis, the first great project of the Modern épistème. |

|

There are excellent resources for studying the medieval world on the Web. Many primary texts are available, as well as some good commentary literature and first rate pics! The best guide to it all I think is the Online reference book for medieval studies. The web at its best, I would say.Following this link might open a new window. Close it (click top left hand box) to come back here. |

Contents |

AGENDA FOR PRESENTATION 1A |

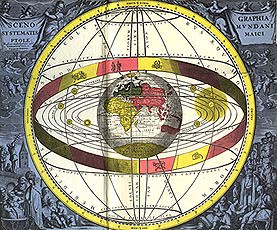

STRUCTURE OF THE MEDIEVAL UNIVERSETHE SPHERESThe universe was held to have the following structure, articulated by Ptolemy in the 2nd Century AD: (Egyptian mathematician, astronomer and geographer, working in Alexandria. His system of astronomy was presented in a work known as Almagest. Here from the Vatican are some pages from an early translation) At the centre is the earth, thought of as spherical. Around the earth

a series of concentric spherical transparent shells, the 'spheres',

or the 'heavens'. Each of the first seven spheres carries fixed onto

it a single luminous body:

An eighth sphere, the Stellatum, carried a number of luminous bodies, the fixed stars - 'fixed' reflecting the fact that they appeared not to change position relative to each other. Beyond the Stellatum was a sphere called the Primum Mobile, the 'First Movable'. It carried no luminous bodies and was invisible to the human eye. In Christian thought, the answer to the question of what lay 'beyond' the Primum Mobile was: God. It was the heaven 'beyond' all the other heavens, or 'the very heaven', cælum ipsum - and the scare quotes are there because it was thought of as beyond space itself, a non-spatial order. Aristotle had made the essential point without any the same reference to God: 'outside' the spatio-temporal order there could be neither time nor space: 'Outside the heaven there is neither place nor void nor time. Hence whatever is there is of such a kind as not to occupy space, nor does time affect it.' Aristotle, De Caelo, 279. (Quoted by Lewis, The Discarded Image, Cambridge, 1994, CUP, p. 97.) The spheres revolved, at speeds that increased with distance from the earth. Diagram of the Universe according to Ptolemy, courtesy R.C.Pine.

|

|

Detailed and beautifully illustrated account of early Greek thinking about cosmology by Ellen N. Brundige.Following this link will open a new window. Close it (click top left hand box) to come back here. |

What do you think?What do you think of this explanation of how change got inaugurated? Do you think the occurrence of change needs an explanation at all? Do you think we have an explanation of it today? Whose expertise is relevant to providing such an explanation? |

|

The medieval interest in the Universe was not primarily in its structure however, nor in how it worked, but in what it, and everything that belonged to it, meant . |

|

For the medievals, Nature was to interpreted , whereas in the Modern world analysis is the mode of understanding.

"To understand and explain anything consisted for a thinker of this time in showing that it was not what it appeared to be, but that it was a symbol or sign of a more profound reality, that it proclaimed something else." (Gilson, quoted by A.C. Crombie, Augustine to Galileo, p.37) Medieval people located themselves not in a structure they thought of as physical, but within a network of meaning. As far as other people are concerned, we follow the same habit. We do not think of our firm or University or corridor or family as primarily a set of physical bodies. It is just that today, we think of the stars and planets as physical bodies deployed in Cartesian space. The fact that the order of the cosmos was regarded as an order of meaning comes out for example in the didactic use nature was put to.

Much of the talk and writing about animals and plants in the medieval period had as its topic their medical users especially the medical uses of plants. But the other really large interest, especially in the early part of the middle ages (until the 13th C) was the guidance animals and to a lesser extent plants gave human beings regarding their conduct, and regarding God's intentions for them. Different animals symbolised different theological elements, and this helped the rhetoric of preaching. The onager for example symbolised the Devil; the panther Christ. The symbolism provided the preacher with powerful illustrations for sermons and reached through that route a large audience. A preacher would go through a list of phenomena or features and attribute them to theologically significant happenings, with the purpose of making those theological points. Here is an example offered by Stannard, which by the way I don't understand, about a reference to the eagle: "Because of sins which take their origin from the mother,

man is like the eagle here, but he is renewed thus: he soars

above the clouds, and feels the sun's fires, despising the world

and its pomp."

Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179) was not a preacher, but in her writing she held that man's fall had had physical effects on nature, causing spots on the moon, wildness in animals,insect pests, animal venoms and disease. Another way in which the concept of an order based on meaning comes through: the doctrine of signatures explained that every plant animal or mineral bore somewhere a sign which indicated its use or virtue. It seems to have originated with Pliny the Elder. |

What do you think?Can we recover today what it would be like to think of the world primarily as a book instead of primarily as a physical structure? Maybe some of us think of the world like this anyway? Can you think of it as a structure of meaning even if you don't believe in a God? |

|

Animals and plants, like human beings, belonged to the sublunary region. They were thought of as belonging, to a single linear hierarchy, a Scale of Nature. |

|

What do you think?The doctrine of the scale of nature is just one expression of the judgement that some things in nature are more important than others. How deep-seated is this perspective? Can we change it? Should we change it of we can? Does it sound plausible to think that it is a perspective that we actually owe to Aristotle, since he gave it clear articulation? |

What do you think?Can we give up the notion of a law of nature as a Law enacted by the Great Legislator and still retain the idea that things in nature MUST behave in certain ways (eg an unsupported stone MUST fall)? In what sense of 'must'? |

|

For reflection: In what sense might we say that the earth has a purpose, or

the human being? In what sense can we say that the whole of creation,

the whole of what there is, might have a purpose? Can the universe

have a purpose if there is nothing outside of itself, if there

is no transcendent God? |

|

|

AGENDA FOR PRESENTATION 1B |

|

|

Against the background of the medieval perspective of things striving to follow the implications of their nature, reason is understood as the guide which tells human beings how to behave so as to fulfil their true nature - or, in Danby's formulation, how to obey the laws of Nature. |

|

Think for a moment of the human being making decisions within the medieval framework. That framework will equip you with the belief that you have a "nature" which you are to "strive" to fulfil. How are you to know how to apply this in particular circumstances? - to decide what to do as you confront particular choices? The medieval answer is: you are provided with your Reason for exactly this purpose. It is your Reason which acts as your pilot, as a guide to show to you what your true nature demands of you: what you should do. The distinctiveness of this conception of reason is highlighted when you contrast it with later perspectives. It is very different from the way of thinking which emerges in the 17th Century. Reason comes then to be seen as a tool, a tool which allows us to make correct inferences, to move from given premises to any conclusion that they support. The premises don't even need to be true: reason discerns the legitimacy of the move, without commenting on the starting point. You remember the point elementary logic texts make much of: there is a vital distinction between truth and validity. We can reason correctly that

but that tells us nothing about the truth of the premise that no swans are black. The reasoning is absolutely correct, though the conclusion reached is wrong. You may have come across the discussion of reason and its role in guiding behaviour that we find in the Modern David Hume: Reason on its own gives us no guidance over what we ought to do: it is our desires that constitute our goals. Reason only comes in to help us see what we should do if we desire to do this or that. "Reason, being cool and disengaged," Hume writes in the Treatise, 1739, "is no motive to action, and directs only the impulse received from appetite or inclination, by showing us the means of attaining happiness or avoiding misery" (Hume, Treatise on Human Nature, 1739, Appendix I) This is the new sense of "reason" at work, and it gets established with the new science. (There is a monumental attempt to restore reason as a guide to the ends human beings should pursue at the end of the 18th Century when what became known as the Romantic Movement tried to check the all-conquering advance of science. It was Kant, heralding this movement, who paradoxically tried to construe reason as a 'prompting of the heart', pointing us along the right path. I try and explain this here. I myself don't see that the attempt was successful. I think we still work essentially with the concept of reason propounded by the early Moderns (and by Locke in particular).) But in the medieval period, "reason" does have to do with truth. It discerns the truth about our nature, and to an extent the nature of other creatures. It discerns for us our aim, what the end of our action should be. It tells us what we ought to do. Reason's primary work, for the medieval, says Danby, "was to guide man in the exercise of his own nature: it illuminated the path man alone, of all the creatures, had to follow." (Shakespeare's Doctrine of Nature, as cited, p.43,4) The Modern conception of nature is different. What is to emerge in the 17th Century is the idea of nature as "a self running machine, set going by an absentee deity, capable of being measured and investigated [by science ...]" (Danby, Shakespeare's Doctrine of Nature, as cited, p.36) |

What do you think?I suggest above that we don't think of reason today as a guide to how we should live. We can reason out what we should do if we want to achieve x, whatever x might be, but we don't think of reason as telling us what we ought to aim for in life. Do you agree? |

The Scholastic notions of form and essenceThe form

We can be quite precise of course about the notions that are basic to medieval thought as it went on in universities. The notion of form is especially worth studying because it is alien to us and because it played a central role in the scientific revolution which brought the medieval period and its conceptions to an end. The form provides 'organisation'The idea that is commandeered from Aristotle by Scholasticism is that an individual animal - e.g. an individual horse - is various bits and pieces (e.g. heart, skin, bone) organised in a certain way. The organisation is provided by the form. (See e.g. R.S. Woolhouse: Descartes, Spinoza, Leibniz, London, 1993, Routledge.) ('Substance' has been used as a term of art for an individual thing organised by a form.) The form gives a thing its identity as a thing of a particular sortThe form was what made this assemblage of matter a horse, and this is the first key thing about the form. It was what made an assemblage of matter a thing of a particular sort. So far therefore we have the notion of a 'substance' as a set of bits and pieces organised by a form, a form which gave the substance its identity as a thing of a certain kind. (Some individual things, according to the Scholastics anyway, do not have forms providing their organisation. A stone would be an example. Maybe one can sense intuitively the distinction they were anxious to acknowledge in this way - a stone, you may think (without being too clear about it!), has much less in the way of organisation than a living thing - its internal structure, you may agree, is much 'simpler'). Anyway, the scholastics thought of a stone as significantly different from a horse. The horse is bits and pieces subject to a form, a stone they called an 'aggregate' - a mere assemblage of smaller bits. Scholastic thinking about forms comes out also in the fact that they regarded things made by human beings as 'aggregates' also. Again, perhaps intuitively one can understand how it might be thought that human beings supply the organisation for artifacts, so that unlike animals which are not put together by human beings, they do not 'require' forms. (I am speaking here of the Scholastic account. It was derived from Aristotle, but his presentation of his own view is confounded rather by his taking a house as his paradigm of a thing with a form. Other things that he says support the thesis that in spite of this unfortunate example he in fact believed that forms were exclusive to living things.) The form grounds a thing's behaviour and propertiesI have said that 'form' is like 'organisation'. But the sense of 'form' is decisively wider. It goes far beyond mere shape for example. In the words of the great Scholastic thinker St Thomas Aquinas: 'A thing's characteristic operations derive from its substantial form.' (Aquinas, ST 3a.75, 76), quoted by Woolhouse, p.10. Commentator Roger Woolhouse indicates the full breadth of the notion when he writes of the form of an oak tree, for example, as follows: '[It] encompasses ... its various parts and their purposes, such as its leaves and bark and their functions; its characteristic activities, such as growth by synthesising water and other nutrients, and its production of fruit; its life cycle from fruit to fruit bearer. It is in being organised and active in this way that the matter which constitutes an oak 'embodies' or is 'informed' by the substantial form 'oak'; it is only by virtue of this that it 'forms' an oak tree at all. The oak's properties and activities 'flow' or 'emanate', are 'formally caused' by its nature.' (Roger Woolhouse, Descartes, Spinoza, Leibniz, London, 1993, Routledge, p.10.) Woolhouse summarises the Scholastic conception by saying that it thought of 'forms as the organising active natures of substances as they develop and change'. (Woolhouse, as cited, p.59.) A thing with a form has the power to initiate changeIf this is the Scholastic conception of form, it leads to a conception of a thing possessing a form as something which has within it a power to initiate change. Unlike the atom of the post Scholastic world, a thing with a form does not necessarily stay put unless and until acted upon by an external force: it can entirely unaided itself launch change. Woolhouse again: 'This is the conception of an individual substance ['substance' in this context, = 'thing'] as active, as something which 'embodies' in itself, as its 'nature', the principles of its development and change. '(Roger Woolhouse, Descartes, Spinoza, Leibniz, London, 1993, Routledge, p. 11.) To explain the properties and behaviour of a thing with a form is to show how they flow from itAnd if this is what a thing with a form is, explaining its properties and its behaviour is a matter of explaining how its properties and behaviour are expressions of its form: 'To understand and explain why an individual substance is as it is, and does as it does, is - except when it is on the passive receiving end of the activities of other substances - to understand how its properties and changing states 'flow' or 'emanate' from the nature, essence or form of the kind of thing it is.' (Roger Woolhouse, Descartes, Spinoza, Leibniz, London, 1993, Routledge, p. 11.) The Role Of 'Form' in the Scholastic Account Of UnderstandingIf we now have an idea of what the Scholastic notion of a 'form', we can move on to explore one way in which this notion was central to their outlook on themselves and on the relationship to things around them. They thought of human understanding, for example, as a matter of our

intellects becoming informed by a 'form'. (Our modern word 'informed'

harks back to this whole way of thinking.) The intellect first renders 'intelligible' the form of the thing being understood, and then grasps and retains that form. That is the Scholastic way of thinking about understanding. Because the form is what makes a thing the sort of thing that it is, it seems to follow that understanding something involves becoming that sort of thing! - since it is a matter of coming to share the form of the thing being understood. This is obviously a very difficult implication to take in board, and scholars disagree about how it is to be undertood. 'Intelligible in actu est intellectus in actu' - these are the enigmatic words which express the Thomist thesis, translated by Kenny as 'thought in operation is identical with the object of thought'. Maybe the thought that today makes most sense to us in coming to terms with this idea is the notion that as one contemplates God the more Godlike one becomes onself. The Scholastics themselves saw the difficulty and solved it in typical fashion by saying that the way in which the form of a thing being understood informed the intellect was different from the way in which it informed the thing itself. (I say this a typical Scholastic move because it sees the problem and solves it to its own satisfaction by an accommodation which sheds not the least bit of light.) One thing we should resist in trying to get our minds round the Scholastic form and the role it plays in the Scholastic understanding of understanding. The thought is that understanding x involves coming to share its form. What we must not do I'm sure is think of coming to share a thing's form as like breaking off a piece of the thing and putting it in our pocket. The notion of 'sharing a thing's form' has probably a closer parallel today in understanding something we are reading. The meaning of a piece of text is not a component of the text which we can somehow get our hands on. Its meaning is rather something we think of ourselves as 'internalising' or 'absorbing'. In some such way as this does the intellect, according to Aquinas, come to share in a thing's form. The notion of a form played a similarly central role in the Scholastic understanding of the other actvities which we today subsume under 'thinking', for example, imagining, The book that explains to me the scholastic way of thinking most clearly (as clearly perhaps as it can be - it actually doesn't impress me very much! - is Anthony Kenny's Aquinas on Mind Routledge, 1993. But see for a rather amazing corrective Robert Pasnau's Theories of Cognition in the Later Middle Ages, Cambridge, 1997, CUP. The form is there too at the heart of how they thought of perception. It emphasises the alien character of Scholastic thought though to realize that for them perception was a bodily function and not one that fell to the 'intellect'. In perception, the sense faculty, not the intellect, was thought of as 'abstracting' the form of the perceived thing from a 'phantasm' of a thing ('phantasm': "something like a mental image" Kenny, AM, p.37). Here is Kenny explaining the significance of hylomorphism and its successor, which I suppose could be called representationalism: "According to some philosophers, in sense experience we do not direcetly observe objects or properties in the external world; the immediate objects of our experience are sense-data, private objects of which we have infallible knowledge, and from which we make more or less dubious inferences to the real nature of external objects and properties. In Aquinas' theory there are no intermediaries like sense-data which come between perceiver and perceived. In sensation the sense faculty does not come into contact with a likeness of the sense-object. Instead it becomes itself like the sense-object..." (Kenny, AM, p.35.) So it is said that Modernity with its representational theory of the mind and of the relationship between our experience and the world (which now becomes the 'external' world) cuts us off from the world and locates us in a quasi-theatre in the head. There we look not at the things about us - trees, tables, other people - but at mental stand-ins for those things - ie representations. |

|

An excellent site offering texts by Aristotle and many other writers from the ancient world (together with related material) is MIT's Internet Classics Archive.Following this link will open a new window. Close it to come back here. |

The Modern rejection of hylomorphic frameworkBut let us just notice how the 'hylomorphic' framework collapsed. The conception of 'understanding' as a matter of sharing forms (as featured by both Ancient and Scholastic thought) is still there in Francis Bacon, even as he sounded his great clarion-call for the revolution (The Advancement of Learning, 1605) at the beginning of the 17th Century. It only falls under the sustained attack of Descartes, Hobbes and decisively John Locke who followed. (More detail here.) THE MIND - AN INNER KINGDOM?

Historically, there was one conception of mind which dominated philosophical thinking in the centuries when Aristotle was accepted as the doyen of philosophers, and there has been a different one since Descartes inaugurated a philosophical revolution in the seventeenth century." [more ...] Anthony Kenny, Aquinas on Mind, London, 1993, Routledge, pp 16,17. No one notion displaced the form of course (or else the change would not have been substantial). What was constructed rather was a new vantage point from which everything looked different. I am tempted to say that the relationship of the human being to the world was re-conceptualised: but that is itself to see things from the new perspective. It is our Modern picture of the human being as an entity distinct from 'the world' and on that account constituting the kind of thing that must have some sort of 'relationship' with the world, that is the 17th century innovation. WITH DESCARTES LEADING THE WAY, THE NEW THINKERS DREW A SCREEN AROUND THE HUMAN BEING, AS ROUND A HOSPITAL PATIENT. FROM THAT POINT ON, THE SHADOWS CAST ON THE SCREENS BY OBJECTS BEYOND HAD TO TAKE THE PLACE OF THE DIRECT COMMUNION WITH THE ORDINARY THINGS AROUND US THAT HAD BEEN ASSUMED BEFORE.I think we might say that what the new thinkers did, with Descartes leading the way, was to draw screens around the human being, as round a hospital patient. From that point on, the shadows cast on the screens by objects beyond had to take the place of the direct communion with the ordinary things around us that had been assumed before. Charles Taylor explains the contrast between Ancient/medieval and Modern conceptions of knowledge like this: "Thought and feeling - the psychological - are now confined [after the Cartesian revolution] to minds. <MORE> In perception, it is the mind's eye now that does the 'seeing': and what it sees are the images of things as they are thrown up on the screens. The world is accessed in perception only via representations - the shadows on the screen. But perception, understood in this way, is then taken as the model for other activities:

all are now treated as species of one genus - thinking; and thinking is regarded as a function of the inner eye and the representations that pass before it. Descartes' contribution to the RevolutionDESCARTES DID NOT HIMSELF SUBSCRIBE TO THE WHOLE OF THE NEW PICTURE.I am talking here of the revolution that was wrought in the 17th century, not all of which was the work of Descartes. In particular, Descartes' view of ideas does not quite give them the 'representational' role that came to be central. DESCARTES DEFENDED THE IDEA OF THE MIND AS A UNITY, BUT DID NOT AGREE THAT IDEAS WERE NECESSARILY REPRESENTATIONAL.There were in fact two prongs, to the revolutionary assault. One was to re-categorise what had previously been regarded as a variety of different kinds of one thing; and the other was to establish a representational model of generic activity - thinking - under which the variety had been subsumed. These two thrusts were in fact sequential.

Descartes mounted the first, but did not himself agree (eg with Hobbes) that thinking was an operation upon representations. (See Descartes, 3rd set of objections and reply, 4th Objection and reply, in The Philosophical Writings of Descartes ed. Cottingham et al. Cambridge, CUP, 1984, pp. 125, 126.) It was John Locke who established the representational point very firmly, by articulating his notion of 'idea' with forthright bluntness ('an idea is whatsoever is the object of the understanding when a man thinks'), by working the concept into a comprehensive 'philosophy', and by getting his work so widely read. With Locke, the notion of the 'idea' became the new fundamental concept. Where the hylomorphic view had seen perception (eg) in terms of a person sharing the form of the object seen, according to the new perspective the object is represented before the mind by an idea. Ideas are 'mental' entities, the only items with which the mind can deal directly, but they stand for the non-mental things about which the thinker has occasion to think. This then is the invention of the mind; and it constitutes one of the foundation stones upon which the Modern framework of conceptions is built. It was, as Rorty explains, ' a single inner space in which bodily and perceptual sensations [...] mathematical truths, moral rules, the idea of God, moods of depression, and all the rest of what we now call 'mental' were objects of quasi-observation.' Richard Rorty, Mirror of Nature, Blackwell, Oxford, 1980, p.50. The connection between mind and bodyOne particular question it raises: What is the relation of the mind to the body? This is construed by Descartes as a question about the relation between an immaterial thinking substance and a material extended substance Descartes himself pursues this question, and puts forward a number of suggestions. Famously he suggests that the connection occurs, and occurs through the Pineal gland. The pineal gland seemed special to Descartes because alone of the structures of the brain it appeared single, undivided, and was located in the middle of the brain. The idea was that a fluid called animal spirits filled the nerves and communicated with muscles and sense organs at one end and the mind at the other. In its central position, the pineal gland was in a good position to interface with the animal spirits as they rose to the brain, or descended to the musculature. Suggestions put forward by others include:

We might ask: what other options might there be?

One corollary of Descartes' account of the human being: the authority of the first person. It is the first person who knows best what he or she is thinking. With later thinkers, what one is thinking - the contents of one's mind - becomes the basis of all knowledge. A profoundly individualistic theme.

|

|

Thomas Aquinas' great work Summa Theologica in a fine Internet presentation.Following this link will open a new window. Close it to come back here. |

What do you think?Is there anything in our Modern outlook which draws on the scholastic 'form' conception? If the scholastics thought of an animal as matter 'organised' by a form, how do we think of one? |

The Emergence of Modern ScienceIn an attempt to cater for polarities in taste, we look at two approaches: As the emergence of the objective study of nature (Thomas) As the stripping of words from the world (Foucault) |

For example, the interest in plants was almost exclusively derived from an interest in their medical uses, (maybe some agricultural interest?). and the way in which they were classified reflects this. The practical orientation is shown in a number of examples given by Keith

Thomas in Man & the Natural World (London 1983 Allen Lane) In a

book by William Coles published in 1656 the categories of plants are defined

thus:

John Parkinson in 1640 used categories such as:

- categories that looked at plants solely from the point of

view of their use or lack of use to human beings. In 1526 the Grete Herbal divided mushrooms simply into two types: "one ... is deadly and slayeth them that eateth them; Tudor herbals highlighted medicinal value, subdividing according to particular healing power. They were of course published to help people identify plants for medicinal purposes. Thomas argues that at the end of the medieval period it was conventional to regard the world "as made for man and all other species as subordinate to his wishes." It was this anthropocentric assumption that was eroded in the Modern period - in the first place, says Thomas, by natural history. (Thomas, p.51.) The situation with regard to animals is similar.

Medieval zoologists had inherited from Aristotle some concern to classify on the basis of anatomy, habitat, and means of reproduction, but they overlay that with their anthropocentric perspective and introduce into their ordering the value of animals to humans as food, in medicine and as the carriers of messages from the Creator about how they should behave. Thomas argues that Buffon in the 18th Century was still maintaining that animals should be ordered according to their relationship to human beings: but just what this meant is less than obvious. (Thomas, p. 53.) The anthropocentrism is anyway clearer with earlier writers such as

Topsell, an English divine writing in his Historie of Foure Footed Beasts (1607), explained that his main point was to show which beasts were the friends of human beings, which could be trusted - and which eaten. (Thomas, p. 53.) John Caius in his Of English Dogges published here in 1576 establishes these categories:

The pre-modern interest in human anatomy was a concern again to do with damage and illness; and so was the interest in physiology. This is why these two areas were flourishing during times when noone thought to see them as parts of wider disciplines, physiology as distinct from human physiology, morphology as distinct from human anatomy. The Arabic tradition was probably more explicitly limited by its concern with healing than that of the West. Francis Bacon is usually read as urging as a novel thing the 'usefulness' of new learning. But this is perhaps a point that would have been accepted as a truism rather than a revolutionary idea. No one would have doubted, at any rate, the usefulness of the old knowledge anatomy and physiology, knowledge of herbs, etc.. The usefulness of the knowledge was its whole point. What happened with the Modern revolution was a challenge to this point: maybe things had a structure, a working, that was interesting for its own sake. The more distant aim might have been utility. But the more proximate one was to gain an understanding of animals and plants (and rocks etc.) based on the premise that there were things to understand there that were quite independent of human needs and practical concerns. Thomas identifies this as the fundamental shift of Modernism: the emergence of the idea that nature had a structure independent of human beings, and one that should be studied. |

Foucault's account of the constitutive features of

the Modern world

|

Signs in the pre-Modern era, says Foucault, were regarded as part of the things themselves. Foucault looks at the accounts of animals and plants from the medieval world and sees that what is presented is a unitary fabric not only "all that was visible of things" but also "the signs that had been discovered or lodged in them."

The signs were included because they were regarded as parts of things themselves ; whereas in the 17th signs become "modes of representation". This was the revolution, according to Foucault. Foucault sees the heterogeneity we have noted in the compilations of material that constituted "natural histories" in the medieval period. Remember the examples of Gesner and Aldrovandi. Another example: Francis Bacon includes 130 topics for inclusion in his

Natural History, of which perhaps two dozen fall within the aegis of natural

history as it came later to be understood. He lists for example:

(Quoted in VP ECSB p. 424.) Another example of "heterogeneity" in the material included in pre-Modern natural history comes from Aldrovandi, as mentioned above.

(Likewise the 'history' of a plant for the pre Modern author involves its virtues, the legends it entered into, its place in heraldry, medicine, food, ancient comment, travellers' comment.) Buffon complains, and we Moderns understand well enough why, that natural histories of this early vintage are stuffed with a "vast amount of useless erudition, such that the subject which they treat is drowned in an ocean of foreign matter." (Quoted in VP ECSB p. 424.) Foucault turns this observation on its head. The editors of these compilations did not regard the material as heterogeneous, he points out: they thought it all belonged together. Distinctions that came to be important later e.g. between observation, document, fable had yet to be drawn. For Aldrovandi, says Foucault, "nature, in itself, is an unbroken tissue of words and signs, of accounts and characters, of discourse and forms." To write an animal's history "one has to collect together in one and the same form of knowledge all that has been seen and heard , all that has been recounted , either by nature or by men, by the language of the world, by tradition, or by the poets. ... Aldrovandi was neither a better nor a worse observer than Buffon; he was neither more credulous than he, nor less attached to the faithfulness of the observing eye or to the rationality of things. His observation was not linked to things in accordance with the same system or by the same arrangement of the episteme. For Aldrovandi was meticulously contemplating a nature which was, from top to bottom, written." So Foucault's thesis here is that words, signs, are not separate from nature in the pre Modern period, but intrinsic to it, woven in with everything else to make a single cloth, and it is language's splitting off from the world that constitutes this most seminal of shifts between pre Modern and Modern thought structures. Prior to the Modern framework, language and discourse are part of nature residing "among the plants, the herbs, the stones, & the animals" (Foucault, p. 35). Under the Modern framework, language is an independent system of signs which can be used to represent nature.

Once the bits in nature can be represented, they can be ordered. Thus the splitting off of language from nature creates the possibility of ordering it. You get a split between signs on the one hand, which now become "tools for analysis, marks of identity and difference ..." and "nature's repetitions" on the other. The new knowledge occupied the area opened up by this split.

Before, words were part of the world. Afterwards they were the tools by which things in the world and their relations were represented. Medieval natural histories are compilations of documents and signs; Modern natural history involves the meticulous examination of things themselves for the first time: and the documents of Modern natural history are not collections of words but "unencumbered spaces in which things are juxtaposed: herbariums, collections, gardens." (Foucault, p.131.) Whereas the Scholastics had been concerned to order their knowledge, Modern thinkers saw it as their task to elucidate the order of the world ... Notes by VP towards substantiating the peeling thesis...

MathesisThis ordering of things, which language splitting from the world makes possible, is the great project of Foucault's first Modern épistème: "... the fundamental element of the classical episteme is neither

the success or failure of mechanism, nor the right to mathematicize nature,

but rather a link with the mathesis, which until the end of the 18th Century,

remains constant and unaltered." The mathesis is a general science of order. What Foucault appears to be saying is that with the 17th Century all knowledge became regarded as the fruit of the general science of order. a science envisaged as embracing all possible knowledge. This is Foucault's way of saying what he thinks "modern science" was, as conceived of at the time of its birth in the 17th Century. It was the idea that knowledge was a sort of ordering. The application of mathematical thinking was just one form of developing the "science of order" it was the application of just one form of order, the quantitative. Numbers of other applications of order were being proposed and conducted as part of the new project. One sort of order was the sort that was being applied to animals and plants. In this case the order was not quantitative. The launch of the science of wealth was another ordering. So was the launch of language science. Analysis is the process by which things are subsumed under an order.

Leibniz attempted to devise a symbol system that would be able to express all forms of order, a vehicle for analysis, whatever it was applied to: "... analysis was very quickly to acquire the value of a universal

method; and the Leibnizian project of establishing a mathematics of qualitative

orders is situated at the very heart of Classical thought..." Thus, the "relation to the mathesis as a general science of order does not signify that knowledge is absorbed into mathematics, or that the latter becomes the foundation for all possible knowledge; on the contrary, in correlation with the quest for a mathesis, we perceive the appearance of a certain number of empirical fields now being formed and defined for the very first time. In [almost] none of these fields... is it possible to find any trace of mechanism or mathematicization; and yet they all rely for their foundation upon a possible science of order. Although they were all dependent upon analysis in general, their particular instrument was not the algebraic method but the system of signs ." Foucault is referring to the analysis of wealth, all sciences of order in the domain of words, being, and needs. You get a split between signs on the one hand, which now become "tools for analysis, marks of identity and difference ..." and "nature's repetitions" on the other. The new knowledge occupied the area opened up by this split. |

ExerciseIn of sub heads under Serpent, which would you include in a full scientific account of the beast (supposing Aldrovandi's list there were one)? This exercise gets at our concept of science and scientific. I am suggesting that the medievals had a concept of medicine , but not of science. |

VP

END OF BLOCK 2

Revised 18:05:03

Gilson,

on the early middle ages:

Gilson,

on the early middle ages: