VI. THE NATURE OF GOTHIC 257

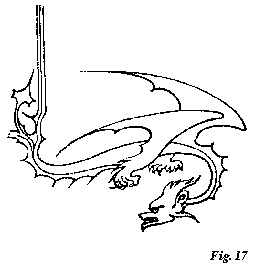

time, we shall find every one of its leaf ornaments surrounded by a thorny structure laid round it in gold or in colour;1 sometimes apparently copied  faithfully from the prickly development of the root of the leaf in the thistle, running along the stems and branches exactly as the thistle leaf does along its own stem, and with sharp spines proceeding from the points, as in Fig. 16. At other times, and for the most part in work of the thirteenth century, the golden ground takes the form of pure and severe cusps, sometimes enclosing the leaves, sometimes filling up the forks of the branches (as in the example fig. 1, Plate 1, Vol. III.), passing imperceptibly from the distinctly vegetable condition (in which it is just as certainly representative of the thorn, as other parts of the design are of the bud, leaf, and fruit) into the crests on the necks, or the membranous

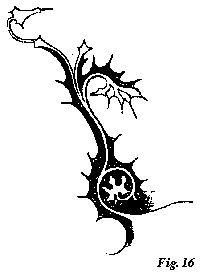

faithfully from the prickly development of the root of the leaf in the thistle, running along the stems and branches exactly as the thistle leaf does along its own stem, and with sharp spines proceeding from the points, as in Fig. 16. At other times, and for the most part in work of the thirteenth century, the golden ground takes the form of pure and severe cusps, sometimes enclosing the leaves, sometimes filling up the forks of the branches (as in the example fig. 1, Plate 1, Vol. III.), passing imperceptibly from the distinctly vegetable condition (in which it is just as certainly representative of the thorn, as other parts of the design are of the bud, leaf, and fruit) into the crests on the necks, or the membranous  sails of the wings, of serpents, dragons, and other grotesques, as in Fig. 17, and into rich and vague fantasies of curvature; among which, however, the pure cusped system of the pointed arch is continually discernible, not accidentally, but designedly indicated, and connecting itself with the literally architectural portions of the design.

sails of the wings, of serpents, dragons, and other grotesques, as in Fig. 17, and into rich and vague fantasies of curvature; among which, however, the pure cusped system of the pointed arch is continually discernible, not accidentally, but designedly indicated, and connecting itself with the literally architectural portions of the design.

§ 95. The system, then, of what is called Foliation, whether simple, as in the cusped arch, or complicated, as in tracery, rose out of this love of leafage; not that the form of the arch is intended to imitate a leaf, but

1 [For Ruskin’s study of illuminated manuscripts at this time, see Introduction to Vol. XII., in which volume are included reports of three lectures on the subject, given at the Architectural Museum in 1854.]

X. R

[Version 0.04: March 2008]