256 THE STONES OF VENICE

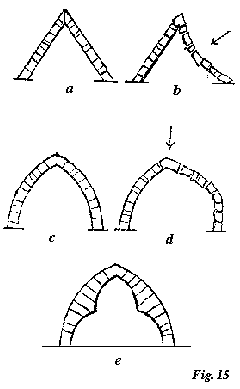

Fig. 15, is the strongest. In fact, the reader can see in a moment that the weakness of the pointed arch is in its flanks, and that by merely thickening them gradually at this point all chance of fracture is removed. Or, perhaps, more simply still:-Suppose a gable built of stone, as at a, and pressed upon from without by a weight in the direction of the arrow, clearly it would be liable to fall in, as at b. To prevent this, we make a

§ 94. The forms of arch thus obtained, with a pointed projection called a cusp on each side, must for ever be delightful to the human mind, as being expressive of the utmost strength and permanency obtainable with a given mass of material. But it was not by any such process of reasoning, nor with any reference to laws of construction, that the cusp was originally invented. It is merely the special application to the arch of the great ornamental system of FOLIATION; or the adaptation of the forms of leafage which has been above insisted upon as the principal characteristic of Gothic Naturalism.1 This love of foliage was exactly proportioned, in its intensity, to the increase of strength in the Gothic spirit: in the Southern Gothic it is soft leafage that is most loved; in the Northern, thorny leafage.2 And if we take up any Northern illuminated manuscript of the great Gothic

1 [See above, § 68, p. 235.]

2 [Compare Proserpina, i. ch. v.]

[Version 0.04: March 2008]