For more information on the work of the Linguistics and English Language Department, visit their website.

Talk of the town

Our linguistics pioneers are world-class.

Our linguistics pioneers are world-class.

If you’ve ever had a ‘barney’ with someone, wondered how Gaelic speakers produce certain sounds or why Scousers’ sentences go up at the end, you may want to read on.

From documenting fascinating underground languages to how we describe living with cancer, words matter. Ranked 3rd in the QS World University Rankings 2024 for Linguistics, the University’s pioneering linguistics team has been at the forefront of research in this field for decades. Whether they are making a difference in the lives of people with dyslexia or helping the NHS improve services, Lancaster’s world-leading Department of Linguistics and English Language examines how language works in learning, communication and within society.

Their work spans vast areas, from improving how we talk about marginalised groups and protect people from online abuse to transforming how we test for language proficiency and document the UK’s many distinct dialects. The University’s pioneering research in this field makes a real difference.

At the heart of it all is a curiosity and championing of the diversity and uniqueness of language in relation to identity.

The underground code that became a brand name

Identity can cover many things, from gender, ethnicity, religion, and sexual orientation to social class, where a person lives, values and personality, and language, which plays a huge part. None more so than Polari - a secret form of language once used by some people in what is now known as the LGBTQ+ community - studied by Professor Paul Baker.

Originally used as a way of conducting conversations in public from the 1950s up to the 1970s, gay people used this language to communicate in a world where being gay was illegal and considered by many to be a taboo subject.

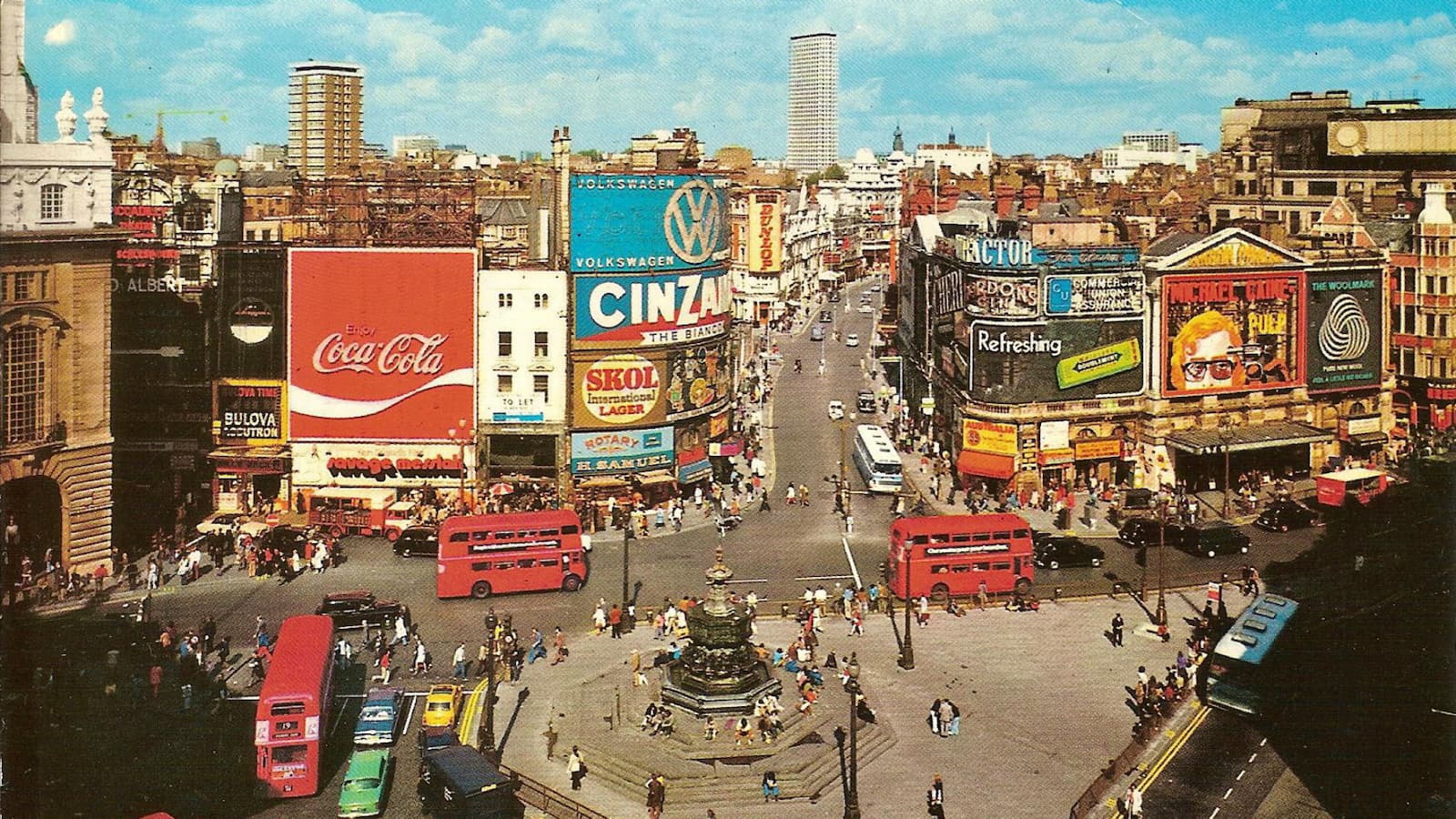

Piccadilly Circus in 1972

For some, it was a collection of around 200 words and phrases and slang words, but others used it in a more complex, formal way, making it sound like a proper language.

Polari developed in London’s West End. Made from borrowed terms from Italian, Cockney Rhyming Slang and Yiddish, it spread throughout clubs and pubs, and new words came and went. It was never written down, so no standardised spellings meant it was ever evolving.

When homosexuality was partially decriminalised in 1967, speaking the secret code started to be seen as ‘naff’ (itself a Polari word that has migrated to the mainstream), with young gay people wanting to be out and engaged with political rights.

But by the 1990s, views changed again, and Polari was adopted by organisations supporting gay communities. Today, a high-end clothing range is named after it, and it even has its own app.

Research explores how newspapers use language

Professor Baker has further explored the ways that language can define an identity in relation to other marginalised groups, including refugees and Muslims.

Working in partnership with the Muslim Council of Britain, Professor Baker and his team explored large collections of news articles documenting their use of language about Muslims.

They found many negative words were commonly associated with the term Muslim, including words like extremist and radical. They found few positive portrayals of Muslims and very few Muslim voices quoted by journalists.

This research was discussed in Parliament, and Professor Baker has also driven real change in the language used around obesity.

Professor Baker said: “We used lots of data, in this case, 36 million words related to topics such as diet and body images in 11 national newspapers over a decade to explore the use of language over time.

“Initially, we found that there was a lot of shaming of people with obesity, particularly in the tabloid media with words like ‘fatty’ and ‘lardy’ showing very little empathy.

“Over time, this shifted to more stories that placed responsibility at the level of the individual, either due to personal decisions about diet and exercise or to aspects beyond their control, like their genes.

“However, at the same time, there have been fewer references to how political decisions and big business impact obesity rates over that time.”

Professor Baker reported his research to the Congress on Obesity last year and has worked with health practitioners to improve their use of language around the subject. Weight Watchers UK asked him for advice about how they use language and representation.

Lancaster’s team was also behind the analysis of 29 million words within NHS patient feedback forms over two years, to provide insight into how the health service can improve patient care and feedback.

By studying the ways that patients used evaluative words like good, awful, and brilliant, they identified how people’s expectations drove their perceptions of a good or bad experience.

For example, people often complained that receptionists were rude or unfair, because they didn’t understand how the appointments system worked. On the other hand, many people dreaded seeing a dentist, and were pleasantly surprised when they didn’t experience the pain, they had been preparing themselves for.

Professor Baker added: “The research revealed that patients tended to give very negative feedback after a single bad experience, but in order to receive very positive feedback, people tended to require a GP practice to provide consistently excellent service over a long period of time.”

“It also showed how different kinds of patients interpreted rating scales. For example, older people were far more likely to give a score of 10 out of 10 but when you look at their written feedback, they use words like ‘satisfactory’. Whereas younger people tended to award lower numerical scores but used extremes of language like ‘fantastic’ and ‘incredible’.”

Other research for Anxiety UK, looking at online forum data, has enabled the charity to use language to specifically targets people differently. Professor Baker found that women tend to see anxiety as part of themselves and something they need to learn to accept and live with, whereas men tend to see it as separate and temporary, and something to be ‘cured’.

Dyslexia as a factor in second language learning

The Department’s research excellence, impact, and the benefits it brings to society have been recognised with many awards, including the Queen’s Anniversary Prize for Further and Higher Education for its work in corpus linguistics. The University is a global leader in many research themes, including foreign languages.

Judit Kormos, a Professor in Second Language Acquisition, was one of only a handful of academics who started studying the role of specific learning difficulties, such as dyslexia, in learning additional languages over 20 years ago.

Professor Kormos said: “I was working in Hungary and looking at how students learn English as an additional language and found that around 10 per cent of students had unexpected learning difficulties. Across the education sector, this is a huge group, yet very little research has been carried out into the challenges these students experience when learning an additional language."

Professor Kormos set about researching the barriers faced by students with dyslexia and the use of inclusive language teaching practices through interviews, questionnaires, and classroom observations.

She said: “It was interesting to find that sometimes learning difficulties like dyslexia were only identified when a person was learning an additional language and started to struggle unexpectedly.

“In contexts where students’ first language has a relatively simple correspondence between spelling and pronunciation, many dyslexic students miss identification. It’s only when they start reading and writing in an additional language that students’ learning difficulties become apparent.

This led Professor Kormos and colleagues to carry out a project funded by the Hungarian National Research Innovation Office that explored the foreign language learning process of dyslexic students. She co-authored a course book with Anne Margaret Smith (Multilingual Matters) and was supported by the European Commission together with international collaborators. She developed teacher training materials and a task bank to both support and inform best practices.

Available via a website and through online courses and free downloadable booklets, these materials have been used around the world, cascading effective methods and best practices from within Europe to South America and Asia.

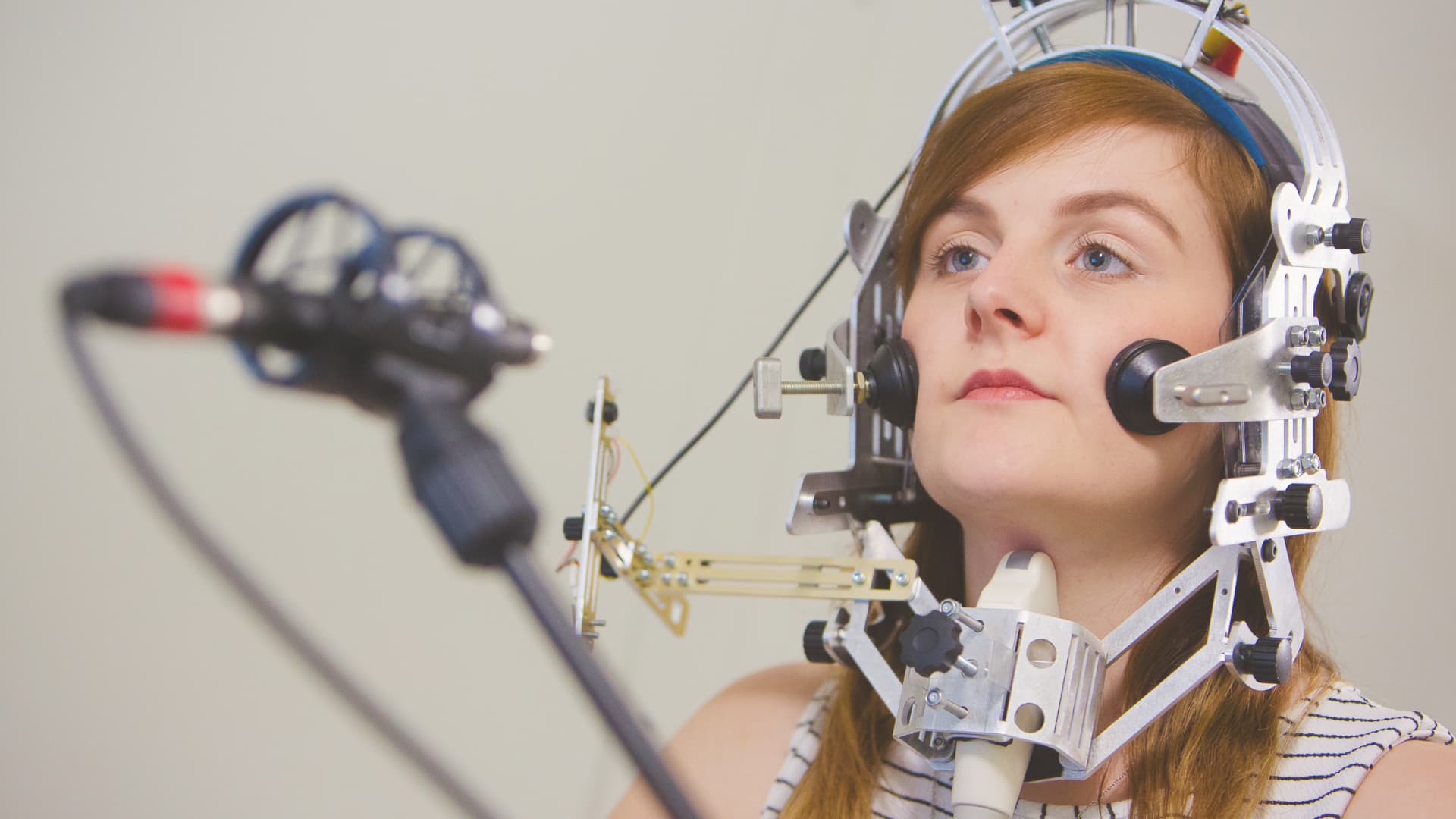

A linguistics laboratory

Professor Kormos said: “A significant issue was teachers not understanding additional learning needs and not having the confidence and skills to teach English as an additional language to students with learning difficulties.

“But by making their classes more inclusive, they’re not just supporting students with special education needs but changing attitudes and increasing acceptance and understanding within all student groups.”

Awarded an ELTons (English language teaching) award from the British Council for excellence in course innovation, this accolade, seen as the ‘Oscars’ of the sector, was recognised for being ‘much needed and addressing a huge gap in the market.’

But Professor Kormos didn’t stop there; she continued her work, expanding into assessment methods and how adjustments during exams can help people with additional learning needs.

She added: “International language tests are expensive yet are essential for many people to be able to find and take up employment.

“Again, by making adjustments that not only benefit those with additional needs, such as allowing them to have more time to complete the test or stop and rewind passages in a listening exam, the anxiety around assessments can be reduced for everyone. Accessibility in English language education is vital, so the more research to help level the field and increase inclusivity, the better.”

Closer to home, Professor Claire Nance and Doctor Sam Kirkham carry out regional dialect research using techniques including ultrasound tongue imaging.

In conversation with market-goers in Blackburn, they took ultrasound images of their tongue positions while saying a word with the ‘r’ sound as in ‘arm.’

Prof Nance said: “The pronunciation of ‘r’ is an unusual feature in the dialect of people from Blackburn and Burnley. It used to be quite common across England and Scotland but has been lost in most of England apart from this pocket of East Lancashire.

“But why? We’re interested in this as we try to understand the history of English dialects, why some aspects are retained and how language and accents change across generations.”

Prof Nance focuses much of her research on Celtic languages, especially Scottish Gaelic, in the context of minority language revitalisation in Scotland.

Uig Sands, The Isle of Lewis

Photograph: Photo by Paolo Chiabrando on Unsplash

She has studied ‘l’ ‘n’ and ‘r’ with Gaelic speakers on the Isle of Lewis. As these sounds are made with interesting tongue shapes, she has used tongue imaging and sound recordings to try and understand how speakers move different parts of the tongue. The research could inform speech therapy and language teaching.

The team’s latest work in Blackburn adds to a growing picture of dialect and identity in northwest England, building on previous work in Liverpool and Manchester.

Prof Nance said: “Despite being geographically close within 40 miles of each other, people living in Manchester and Liverpool have very different dialects. For example, our work shows that people in Liverpool have a low-rising intonation and do not gain the final pitch until the end of the phrase.

“This intonation is typologically unusual and hadn’t been the subject of detailed previous work. It’s often assumed that the intonation of this dialect was due to mass immigration from Ireland. But this is too simplistic and doesn’t account for dialect variation in Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland.

“Having researched its origins, we found that the rising intonation probably wasn’t the majority variant when Scouse was first formed but may have been adapted to accommodate the new diverse community established in the city.”