Wordsworth was not the only literary celebrity that Victorian tourists would have associated with the Lake District, but he was widely regarded as the region’s pre-eminent cultural authority. Quoted in guidebooks, his words were credited with casting an ‘imperishable lustre’ on the local scenery.1 Consulted by tourists, his works were assiduously mapped over the terrain.

By the 1850s, this associative fusion of poet and place had become absolute, making the Lake District one of England’s foremost literary localities. As the American poet James Russell Lowell affirmed in 1854, tourists who travelled to the Lakes during the mid-19c did so in order to visit ‘Wordsworthshire’, a ‘literary country’ consecrated by the works of a single poet and his circle.2

Chief amongst the attractions of Victorian Wordsworthshire was Rydal Mount, the house

where the poet had resided with his family from 1813 until his death in 1850. Yet, for all its pre-eminence, Rydal Mount was not the only spot frequented by those tourists who wished to visit the scenes of Wordsworth’s life and his works.

Indeed, as Samantha Matthews has shown, the poet’s former home was closely seconded in prestige by his final resting place in St Oswald’s churchyard, in Grasmere.5 Other places, such as the nearby village of Hawkshead (the scene of the poet’s schooldays), also merited a good deal of attention, as did various sites along the course of the Duddon (the river celebrated in Wordsworth’s famous sonnets).

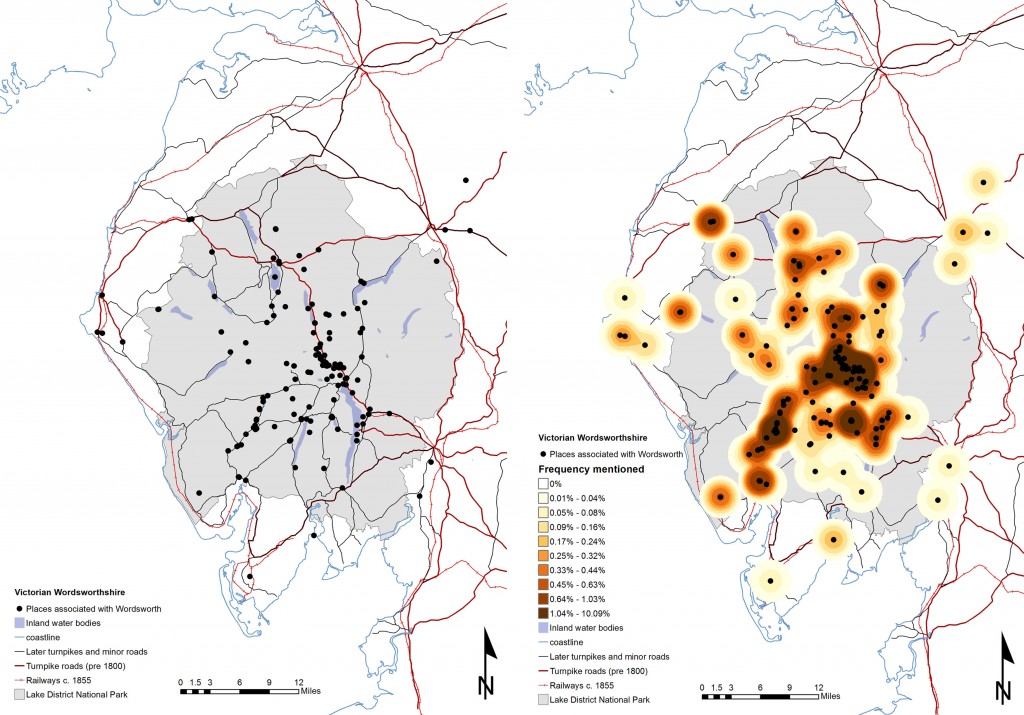

Nor were the sites noted by Wordsworth’s Victorian audience were confined to the central and southern fells. In fact, as a quick consultation of contemporary tourist publications confirms (figure 1), at least 160 other spots throughout the region, from Kendal to Cockermouth and from Brougham Castle to St Bees, also had Wordsworthian connections deemed worthy of the reader’s attention and esteem.

Figure 1. In this sample of nearly two dozen Victorian Lake District tourist publications, places explicitly associated with Wordsworth are shown to be distributed throughout the greater Lakes region. In all, these publications connect the poet to 164 different places a total of 529 times. Modern readers may find the broad distribution of these Wordsworthian locations (as seen on the left) surprising. Yet, if we take the frequency with which thy are mentioned into account, then the underlying pattern begins to look more as one might expect. As the density-smoothed map on the right illustrates, the highest concentration (57% of the total number places) is located within a five mile radius of Rydal Mount, with almost all of the rest falling well within the confines of the modern Lake District National Park. Notably, Rydal Mount, the most frequently mentioned location, accounts for nearly 10% of the total. Grasmere and St Oswald’s churchyard, the next two most frequently mentioned locations, count for 5% and 4% respectively. Dove Cottage, which begins to feature regularly in guidebooks in the late 1870s, counts for 2% overall.

Figure 1. In this sample of nearly two dozen Victorian Lake District tourist publications, places explicitly associated with Wordsworth are shown to be distributed throughout the greater Lakes region. In all, these publications connect the poet to 164 different places a total of 529 times. Modern readers may find the broad distribution of these Wordsworthian locations (as seen on the left) surprising. Yet, if we take the frequency with which thy are mentioned into account, then the underlying pattern begins to look more as one might expect. As the density-smoothed map on the right illustrates, the highest concentration (57% of the total number places) is located within a five mile radius of Rydal Mount, with almost all of the rest falling well within the confines of the modern Lake District National Park. Notably, Rydal Mount, the most frequently mentioned location, accounts for nearly 10% of the total. Grasmere and St Oswald’s churchyard, the next two most frequently mentioned locations, count for 5% and 4% respectively. Dove Cottage, which begins to feature regularly in guidebooks in the late 1870s, counts for 2% overall.

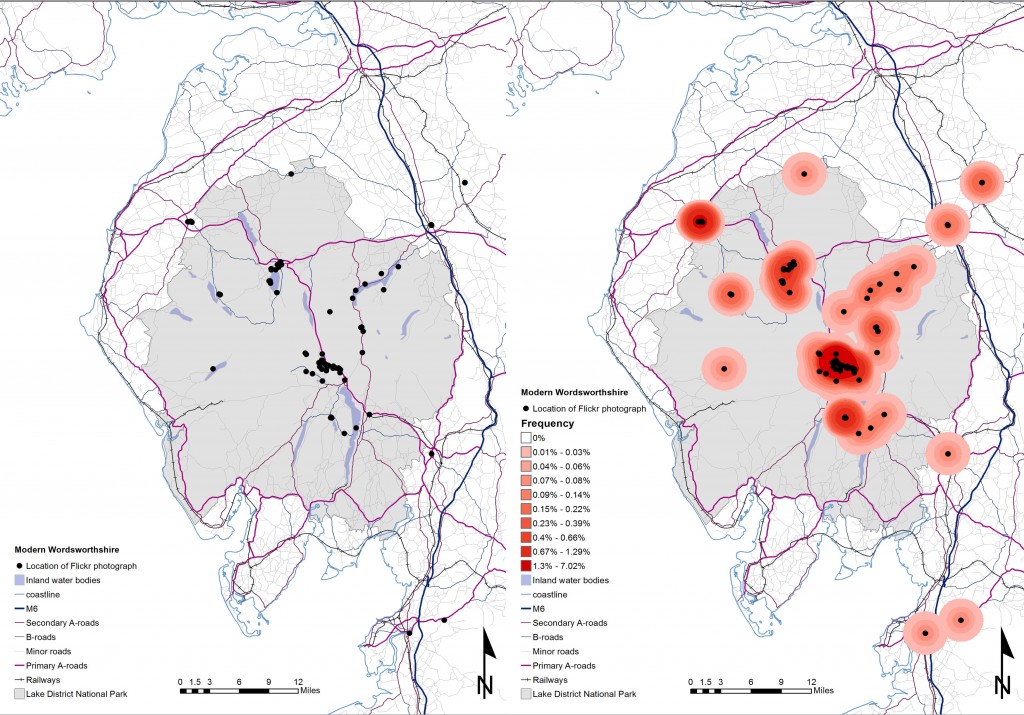

Victorian Wordsworthshire, when surveyed in this way, would seem to cover a fair bit of ground: more ground than one might expect given the concentration of the contemporary Wordsworth industry around Grasmere and, to a lesser extent, Cockermouth and Hawkshead. Certainly, if annotated photographs posted on Flickr© are any indicator, the poet was associated with a much wider array of locations around the Lakes in the past than he is in the present (figure 2).

At first glance, the scattered pattern of the points plotted above appears to support this impression. Moreover, it corroborates the claims of scholars like Saeko Yoshikawa, who contends that the ‘Wordsworthian pilgrims’ of the past were more ‘intrepid’ than we might assume, and that they visited more sites and, frequently, covered more ground than tourists typically do today.6 At the same time, it is also clear that, notwithstanding the range of Wordsworthian sites tallied in these publications, Victorian Wordsworthshire was a fairly coherent and centralized entity.

Figure 2. These maps show the location and frequency of 200 photos uploaded to Flickr© that include both geographic coordinates and the word ‘Wordsworth’ in their metadata. The pattern here is much less diffuse than in figure 1, with the highest points of concentration being located around Grasmere, Rydal, Hawkshead, and Cockermouth: all sites of prominent Wordsworth memorials and/or museums. At the same time, however, these maps do suggest that Lake District tourists today are more interested in the Wordsworthian associations of specific places than their Victorian forebears. This, of course, has a good deal to do with how the Wordsworthian canon has changed over time. The average reader today is, after all, more inclined towards Wordsworth’s early verse than to his mature works. Thus, few are likely to have bothered to peruse later poems such as ‘Stanzas Suggested in a Steam-Boat off St Bees’ Heads’ (pub. 1835), let alone to have been prompted thereby to associate Wordsworth with the coastal village. By the same token, readers today are proportionately more interested in the Wordsworthian associations of Ullswater, which appears as a marginal site of interest in figure 1 (where one finds a cluster near Lyulph’s Tower and Aira Force). This is likely owing to the contemporary popularity of ‘I wandered lonely as a cloud’ (pub. 1807), which is famously reported to have been inspired by the sight of daffodils along the banks of Ullswater.

Figure 2. These maps show the location and frequency of 200 photos uploaded to Flickr© that include both geographic coordinates and the word ‘Wordsworth’ in their metadata. The pattern here is much less diffuse than in figure 1, with the highest points of concentration being located around Grasmere, Rydal, Hawkshead, and Cockermouth: all sites of prominent Wordsworth memorials and/or museums. At the same time, however, these maps do suggest that Lake District tourists today are more interested in the Wordsworthian associations of specific places than their Victorian forebears. This, of course, has a good deal to do with how the Wordsworthian canon has changed over time. The average reader today is, after all, more inclined towards Wordsworth’s early verse than to his mature works. Thus, few are likely to have bothered to peruse later poems such as ‘Stanzas Suggested in a Steam-Boat off St Bees’ Heads’ (pub. 1835), let alone to have been prompted thereby to associate Wordsworth with the coastal village. By the same token, readers today are proportionately more interested in the Wordsworthian associations of Ullswater, which appears as a marginal site of interest in figure 1 (where one finds a cluster near Lyulph’s Tower and Aira Force). This is likely owing to the contemporary popularity of ‘I wandered lonely as a cloud’ (pub. 1807), which is famously reported to have been inspired by the sight of daffodils along the banks of Ullswater.

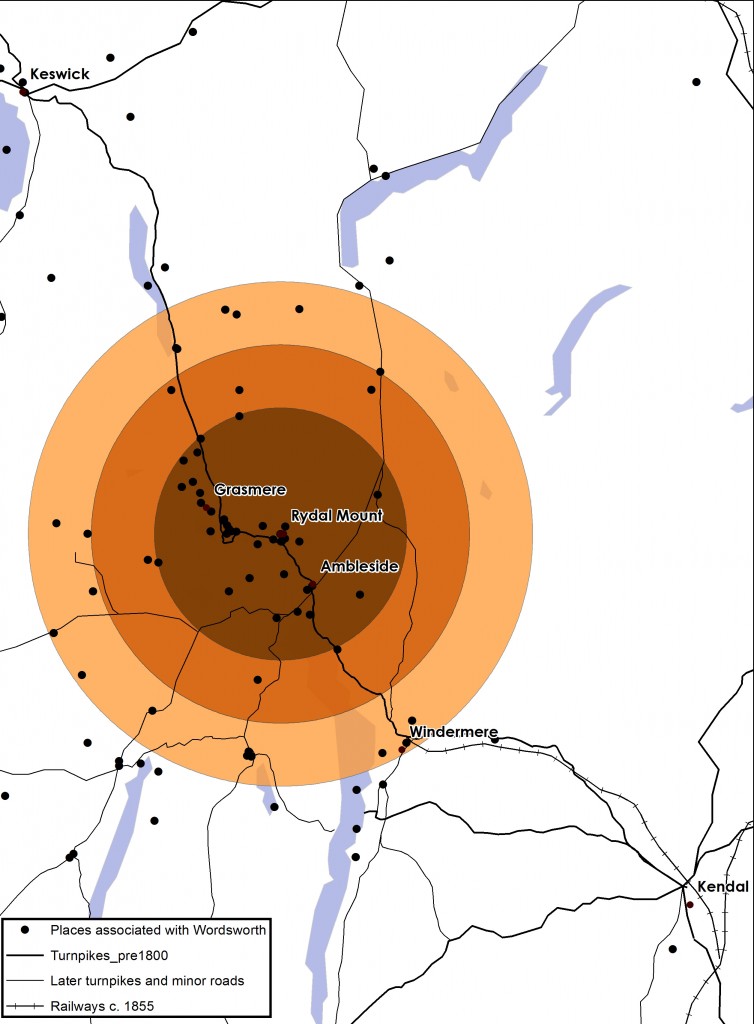

One does, to be sure, find a few references to outlying locations, such as St Bees, which attract less attention today. Those places mentioned most frequently, however, are either found within a short distance of Rydal Mount (figure 3), or at least located well within the confines of the present-day Lake District National Park.

Figure 3. Though places associated with Wordsworth are distributed around the Lakes region, a significant number all close to the poet’s home, Rydal Mount. As illustrated above, 218 (or 41%) of the 529 locations mentioned in connection with Words-worth are found within half a mile of the house, with 231 (44%) being found within one mile and 302 (57%) within one and a half miles.

Figure 3. Though places associated with Wordsworth are distributed around the Lakes region, a significant number all close to the poet’s home, Rydal Mount. As illustrated above, 218 (or 41%) of the 529 locations mentioned in connection with Words-worth are found within half a mile of the house, with 231 (44%) being found within one mile and 302 (57%) within one and a half miles.

This is an intriguing revelation, as it suggests that although Victorian tourists were encouraged to regard Wordsworth as the presiding ‘genius’ of the entire Lakes region, they were mainly prompted to identify the poet with a number of key locations in the centre of the region.

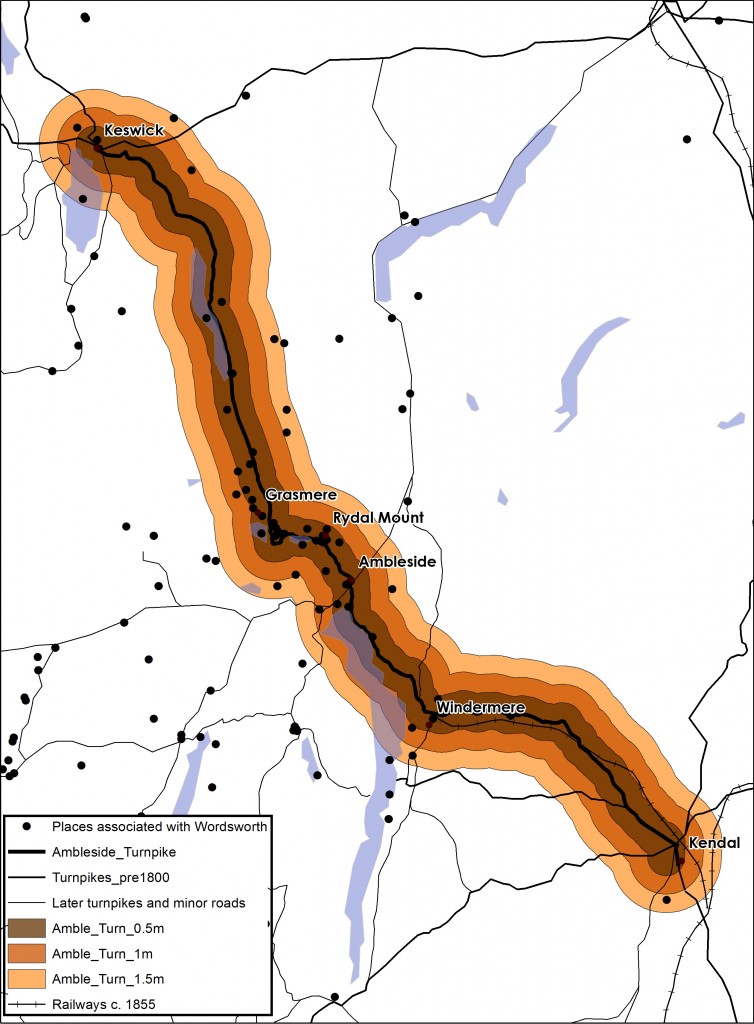

Even more intriguing than this, however, is the fact that almost all of sites mentioned in these texts fall along – or are, at least, visible from – the region’s main routes and thoroughfares. Notably, as the accompanying maps illustrate, three-quarters of the places that Victorian tourists seem to have regularly associated with Wordsworth are clustered around the coach roads in the central and southern parts of the district. In fact, half of them are actually located along a single roadway: the old turnpike from Keswick to Kendal, which, for the most part, lies beneath the tarmac of the modern A591 (figure 4).

Figure 4. Running through the very heart of the Lake District, this roadway has served for centuries as one of the region’s main arteries. Its importance – though principally based on the way it connects the commercial centres of Ambleside, Windermere, and Keswick (and, at a further remove, the markets of Kendal, Cockermouth, and Whitehaven) – was further augmented in the Victorian era by its status as Wordsworshire’s principal trunk-road. As shown here, nearly half of the 529 locations associated with Wordsworth in figure 1 fall within a mile and a half this route; more than 80% of these are less than half a

mile from the road.

We’ll be posting more about this case study in the weeks to come. In the meantime, we’d be keen to hear your thoughts about our initial findings.

Notes:

1 Qt. J.B. Payne, Lake Scenery of England (London: Day & Son, 1859), p. v.

2 James Russell Lowell, ‘Sketch of Wordsworth’s Life’, The Poetical Works of William Wordsworth, 7 vols. (Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1854), I, xxxviii. On the phenomenon of ‘literary countries’, see Nicola Watson, The Literary Tourist: Readers & Places in Romantic & Victorian Britain (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006), pp. 169-70.

3 Qt. Harriet Martineau, ‘The Lake District’, The Land We Live In: A Pictorial and Literary Sketch-Book of the British Empire, 4 vols., ed. Charles Knight (London: Charles Knight, 1847), II, 223.

4 Qt. William Wordsworth, The Excursion: Being a portion of ‘The Recluse’, A Poem (London: Longman & Co., 1814), p. ix.

5 Samantha Matthews, Poetical Remains: Poets’ Graves, Bodies, and Books in the Nineteenth Century (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), pp. 154-88.

6Saeko Yoshikawa, William Wordsworth and the Invention of Tourism, 1820-1900 (Ashgate: Farnham, 2014), pp. 8-9.

© Spatial Humanities: Texts, GIS & Places

© Spatial Humanities: Texts, GIS & Places