Workers continuing to leave the labour market will undermine growth plan

Posted on

© from the Centre for Ageing Better's age positive image library

© from the Centre for Ageing Better's age positive image library

Despite the impact on the cost of living crisis on households across the UK, this month’s labour market statistics show that workers are continuing to leave the labour market. This presents a challenge to the Government’s growth plan, and there is a need for new approaches to support people out of economic inactivity and back into labour market.

Fall in unemployment is driven by younger workers returning to education

This month’s labour market statistics show that unemployment has fallen to 3.5%, a new record low not seen since 1974. The overall fall in unemployment is driven by a decline in short-term unemployment in particular. This usually suggests people have either found employment, or they have stopped looking for work.

In this case, the decrease in unemployment is largely driven by young workers aged 18-24, who have entered full-time education and have, for the moment at least, stopped looking for work. There is a cyclical element to this, with people returning to education over the autumn. As we know that long-term unemployment can be particularly harmful for young people’s prospects, the uptake of education could be considered positive.

Inactivity continues to grow

We are witnessing workers continuing to leave the labour market. This quarter, the proportion of working age adults who are out of work and not looking for work, termed economic inactivity went up by 0.6 percentage points, representing 252,000 people. Combined with falling employment levels and falling unemployment levels, this means there is a net flow from employment and unemployment into economic inactivity.

Right now, the proportion of the workforce not in work and not looking for work stands at 21.7%. Historically, this is not the highest it has ever been. However, the reasons older workers have provided for leaving the labour market over recent months are concerning, as they are driven particularly by an increase in long term illness. Overall, the number of people who reported they were not looking for work due to long term sickness increased this quarter by 169,000, to nearly 2.5 million.

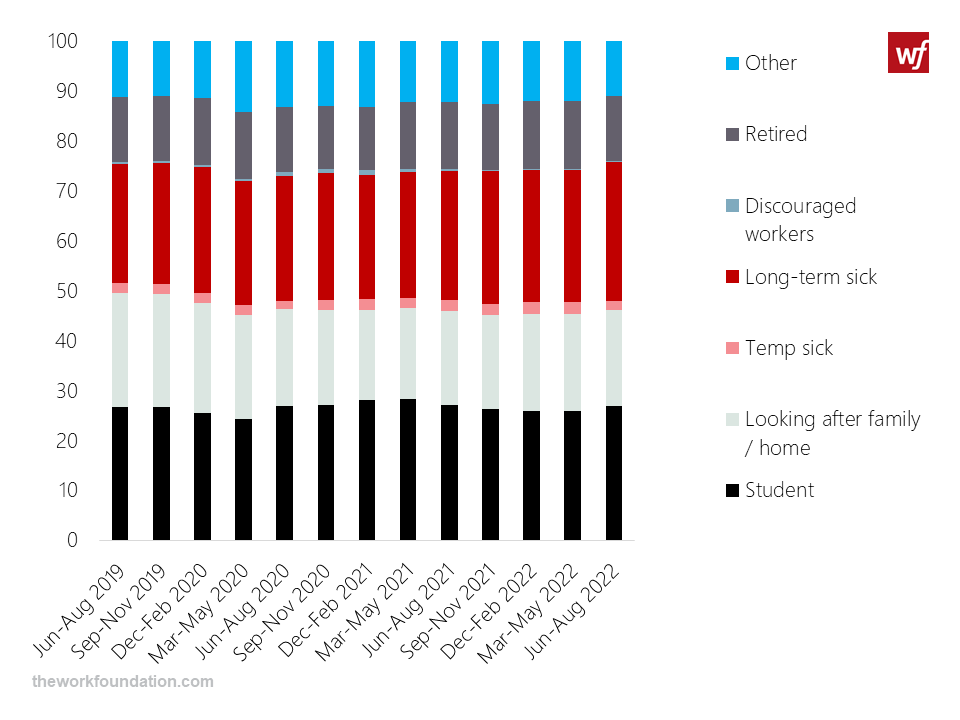

This means that in June-August 2022, long-term sickness composed 27.7% of the overall number of people out of work and not looking for work. This compares with 23.8% in the same quarter of 2019 prior to the pandemic, or a real term increase of 421,000 people. Older workers aged 50-64 compose a large share of the overall growth in inactivity and in the growth in people reporting long term sickness.

Figure 1: Increasing share of inactive composed of long-term sick

Source: Work Foundation calculations based on ONS (11 October 2022) Dataset A01 October – Economic inactivity reason for those aged from 16-64 (seasonally adjusted). This figure represents changes in the levels of different reasons for economic inactivity between June-August 2019 and June-August 2022.

Case for an interdepartmental effort to address participation

At the “mini-budget” in September, the Chancellor announced increased support from work coaches in Jobcentres for workers over 50, aiming to get older people back in work. However, to make use of Jobcentres, people must be on Universal Credit.

According to the latest ONS data, just 12.7% (505,412) of those who are economically inactive and aged 50-65 were on Universal Credit during April-June 2022. This means that there are close to 3.5 million people aged 50-65 who are inactive but not on Universal Credit, and therefore would not be eligible for employment support if they wanted to get back into work.

DWP should look for ways to improve outreach and provision for older people and individuals with long term health conditions, for example by commissioning support through external organisations with experience in supporting people who face complex barriers to entering and staying in work.

But for a truly coherent approach to labour market participation that will manage to reach and support a much wider group of people than those getting Universal Credit, government agencies and departments dealing with this same issue should be brought together into a Taskforce for Participation.

Given that ill health is such a driver of premature labour market exits, this should include the Department of Health and Social Care. Additionally, the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy and the Government Office for Equalities could bring to bear their expertise in liaising with employers and seek to improve job design in organisations in ways that would enable older workers to return to work.

Related Blogs

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed by our bloggers and those providing comments are personal, and may not necessarily reflect the opinions of Lancaster University. Responsibility for the accuracy of any of the information contained within blog posts belongs to the blogger.

Back to blog listing