What should the next Prime Minister prioritise to prevent a labour market crisis?

Posted on

© Photo by Komarov Egor on Unsplash

© Photo by Komarov Egor on Unsplash

This month’s labour market statistics show early signs of an oncoming crisis. With inflation now at 9.4%, real wages have fallen sharply, the cost of living crisis is biting, and worse is looming. Last week Bank of England increased the base rate by 0.5 percentage points to 1.75% - the largest increase in 27 years. New forecasts suggest energy bills could rise even further this winter than previously predicted. One in six households are estimated to be in “serious financial distress” and will be struggling with the increase in costs.

Having proven during the pandemic that Government intervention in the labour market can successfully mitigate the impact of an economic crisis on businesses and workers’ lives, the new Prime Minister should lead on timely and strategic interventions this autumn.

Falling wages continue to ramp up living cost pressures

The current high levels of inflation continues to put wages under pressure. Although on average pay increased by 4.7% over the past year, real wages accounting for inflation and excluding bonuses are now worth a record 3.0% less than they were a year ago. But these effects are not equally felt; while the private sector has seen an average wage increase of 5.4%, public sector pay increased by only 1.8% between quarter 2 2021 and 2022.

Spiralling costs for essentials from energy to groceries are a pressing concern. In mid-July, nearly 9 in 10 (89%) people surveyed by the Office for National Statistics said that their cost of living had increased and one in four (75%) were very worried about it. The latest data suggests money worries may be driving some retirees to return to work.

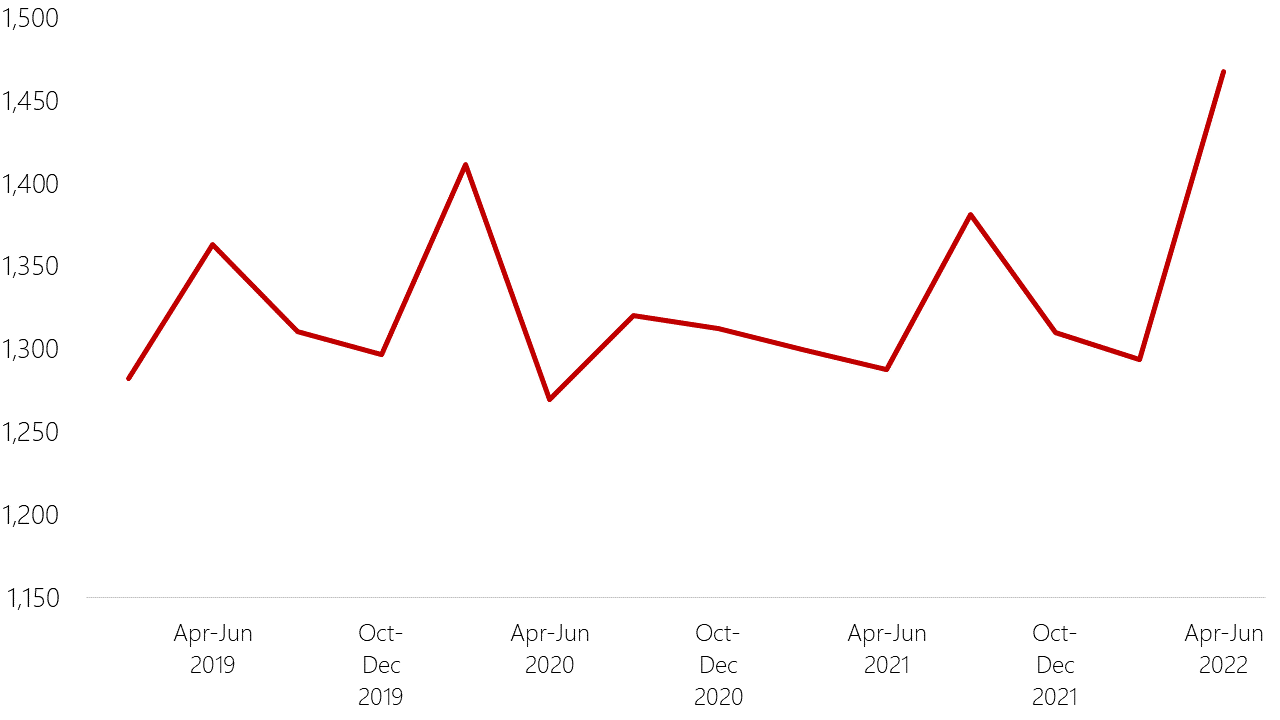

In April-June 2022, employment levels among people aged over 65 went up by 13% (173,000) on the quarter and inactivity decreased by nearly just as much (167,000). Although the pension age has increased from 65 to 66, this doesn’t seem to fully account for the change over the last quarter because we would expect to see increased labour market participation in older age groups spread across the past year. This could suggest that some workers are ‘unretiring’ to cope with the increased cost of living.

Figure 1: Employment levels people aged 65+, 2019-2022

Source: Work Foundation calculations based on ONS (16th August) Dataset A01 August – Employment levels among 65+

Vacancies are slowing while redundancies reach a record low

As Covid-19 restrictions eased, employers started hiring and job vacancies hit record highs earlier in 2022. Today’s statistics show job listings have started to come down from that but still remain high. There were 1.27 million vacancies between May and July 2022, a decrease of 19,800 on the previous quarter, although there are still 456,000 more vacancies than there were between May-July 2019.

Given the uncertain economic outlook and the cost pressures employers are facing, this could mark the start of a slowdown in hiring that we can expect to become more pronounced in the second half of this year.

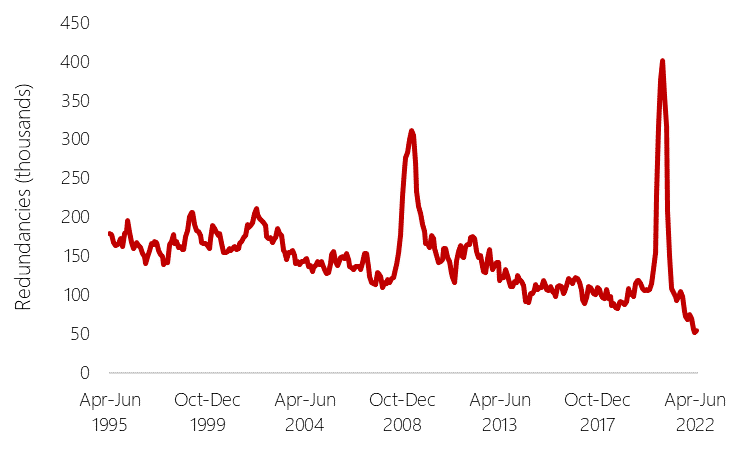

Given the recruitment challenges many employers are continuing to grapple with, it is perhaps unsurprising that some employers are focusing on retaining their staff. Even still, it is remarkable to see redundancies are at their lowest ever level, with just 54,000 (1.9 per 1,000 employees) between April and June 2022. This is a significant decrease on the quarter (70,000 redundancies between January and March 2022) and on the year (98,000 redundancies between April and June 2021), as shown in figure 2 below.

Figure 2: Redundancy levels for those aged 16 and over, April-June 1995 – April-June 2022

Source: Work Foundation calculations based on ONS (16th August) Dataset A01 August - Redundancies levels and rates for those aged 16 and over

However, warnings of a looming recession create uncertainty for employers and employees alike, and there could be growth in redundancies over the months ahead. The recession of 2008-9 saw the economy shrink for five quarters in a row, which led to mass redundancies and unemployment reaching its highest rate since 1995. While the Bank of England has suggested that this crisis is not set to be as deep as 14 years ago, it may last just as long. Without action from Government, uncertainty remains as to whether redundancies could once again reach the record high seen during the peak of the pandemic (402,000 or 14.5 per 1,000 employees between Sept-Nov 2020).

Key actions for the new Prime Minister’s first 30 days in office

The energy price cap is due to rise again in October to around £3,500 and in January 2023 to £4,266, which will increase the enormous financial strain many households are already experiencing and will impact lower income households the hardest.

Although the previous Chancellor has provided two one-off payments to ease cost of living pressures over summer, the forecasts for energy prices and inflation have changed significantly since that package was introduced. Considering the revised forecast, this will not be enough and should prompt the new Prime Minister to consider a longer-term approach to managing the economy’s impact on households.

The UK response to the pandemic has shown that Government intervention in the labour market can be highly effective. During Covid-19, the Coronavirus Job Retention (furlough) Scheme (CJRS) played a key role in mitigating the impact of the economic fallout on both businesses and workers. This enabled employment levels to remain low throughout the pandemic and allowed the majority of furloughed workers to return to their jobs once business activity resumed.

The new Prime Minister should consider bold policy intervention to head off the forecast labour market crisis and offer certainty and stability to workers and employers alike.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed by our bloggers and those providing comments are personal, and may not necessarily reflect the opinions of Lancaster University. Responsibility for the accuracy of any of the information contained within blog posts belongs to the blogger.

Back to blog listing