How well prepared are we for rising living costs in 2022?

Posted on

© Photo by KWON JUNHO on Unsplash

© Photo by KWON JUNHO on Unsplash

This month’s labour market statistics show continued signs that the furlough scheme was successful in protecting employment. Payroll data from HMRC indicates that in December 2021 there were 29.5 million employees in the UK, and the latest Labour Force Survey estimates for September to November 2021 suggest that the employment rate has increased 0.2 percentage points on the quarter to 75.5%. Furthermore, the redundancy rate decreased to 3.5 per thousand employees, which is below the rate seen pre-pandemic.

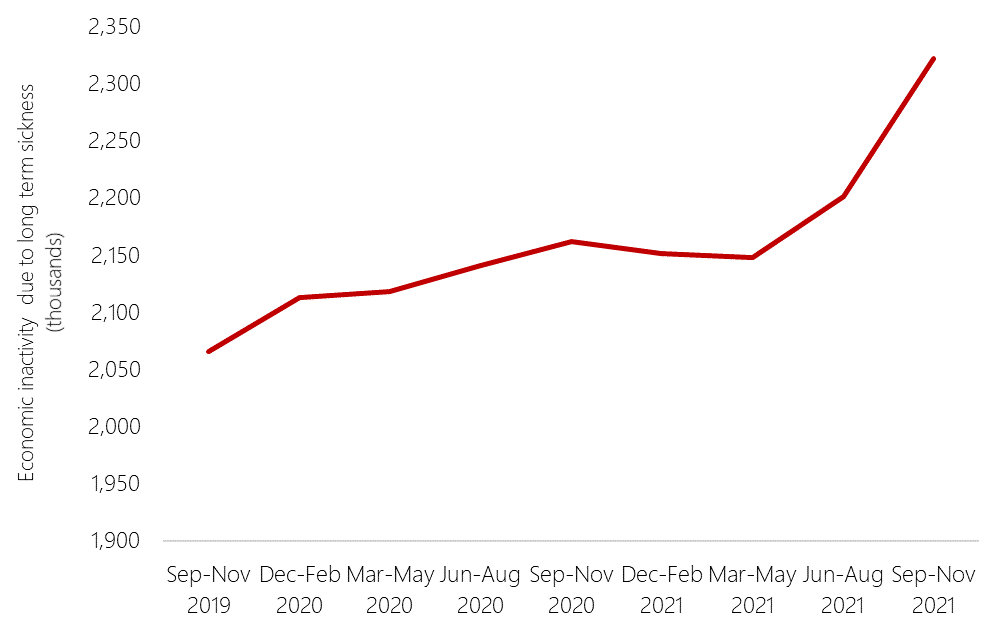

However, there are still causes for concern. Labour market participation has fallen through the crisis, with the number of people unemployed but not actively seeking work (economically inactive) remaining high at 21.3%. Worryingly, this is driven by increasing numbers of people experiencing temporary or long-term sickness.

Figure 1: Economic inactivity due to long-term sickness, Sep-Nov 2019 – Sep-Nov 2021

Source: Work Foundation calculations using ONS Dataset: A01 - Economic inactivity for those aged from 16 to 64 (seasonally adjusted). 18 January 2022.

Furthermore, inactivity data highlights that both older and younger workers are facing barriers in entering or re-entering work. Economic inactivity has increased on the year across all age categories except for those aged 35-49, where it has decreased by 3.2%. Indeed, mid-career workers are more likely to have the experience that employers are looking for, and might not face some of the potential barriers that older workers often have to contend with, such as negative employer attitudes, increased caring responsibilities and long-term health conditions.

As highlighted by the Centre for Ageing Better, it is vital that we engage workers of all ages and generations in work, as from an economic perspective there are not enough young people flowing into the labour market to fulfil its requirements on volume alone. Furthermore, many older people are not choosing retirement out of a desire to stop working, but because they feel rejected by the labour market and struggle to find a way back to work. They are likely to lose out, not just financially but also in health, social connections, and a sense of purpose.

However, recent employment support programmes focussed on either young people (such as the Kickstart Scheme) or supporting those closest to the labour market via additional finding for Jobcentres and the Restart Scheme. While these types of support may benefit some worker groups, they generally haven’t worked as well for disabled or older candidates in the past.

Today’s data appears to show wage growth slowing down, although the actual picture might be more complex than that given the growth in lower paid work, combined with wage growth in some sectors that are currently experiencing shortages. However, it's clear that many workers are stuck on low pay as we face increasing cost pressures over the coming months.

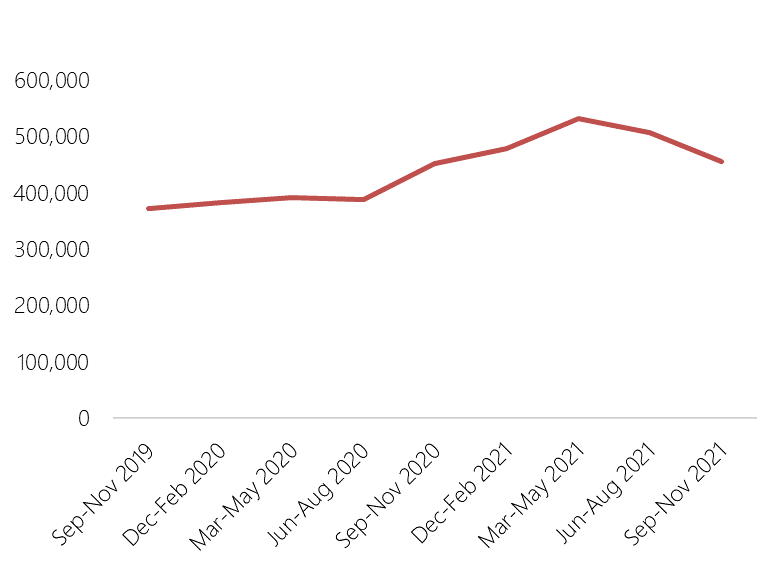

New research from the Joseph Rowntree Foundation indicates that two-thirds (68%) of working-age adults in poverty live in a household where at least one adult is in work. While an increase to the wage floor is on the horizon, with minimum wage levels set to increase in April, this can only do so much if workers are not getting the hours or security that they need in the first place. This is illustrated by the fact that there are still 911,000 part-time workers who could not find a full-time contract, which remains higher than pre-pandemic levels, despite decreasing by 10% on the year. There are also still 455,000 workers on temporary contracts because they could not find a permanent job, a significant increase on pre-pandemic figures, although this growth has slowed.

Figure 2: Number of involuntary temporary workers, Sep-Nov 2019 – Sep-Nov 2021

Source: Work Foundation calculations using ONS Dataset: A01 - Full-time, part-time and temporary workers (seasonally adjusted). 18 January 2022.

Rising inflation, particularly soaring energy costs also raise specific issues for welfare policy. Recent IFS research indicates that those on low incomes will tend to find it hardest to tide themselves over during a period in which their real incomes are eroded, which by default is what happens when inflation increases sharply because most welfare benefits increase in line with a lagged measure of inflation. This is compounded by the fact that the UK’s social security system is among the least generous of all OECD states.

Therefore, Government needs to urgently prioritise protecting those on the lowest incomes from a sharp fall in living standards, starting with reinstating the £20 per week uplift to Universal Credit payments. Additionally, more recent CPI data should be used to inform annual uprating, to ensure rates better reflect changes in living costs.

While the Plan for Jobs helped limit rises in unemployment, it is evidently not doing enough to bring people back into the labour market, and into secure and well-paid jobs. Support should be tailored to individual needs and delivered by or alongside organisations with expertise and established trust among these groups. For example, models such as peer support and individual placement and support have had proven positive health and employment outcomes for disabled people. Informed by this evidence, Government should develop a new, long-term strategy to tackle barriers to employment and improve participation which reflects the distinct needs of different groups including older, younger and disabled workers.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed by our bloggers and those providing comments are personal, and may not necessarily reflect the opinions of Lancaster University. Responsibility for the accuracy of any of the information contained within blog posts belongs to the blogger.

Back to blog listing