Economic inactivity due to long-term ill-health at record high

Posted on

© Picture by Ben Garratt on Unsplash

© Picture by Ben Garratt on Unsplash

Last week, the Work and Pensions Secretary, Mel Stride MP suggested that bringing those who are out of work and not looking for work back into the labour market would provide substantial economic gains and provide the fiscal space for a future tax-cut. It is true that growth is hard to achieve with a workforce that is substantially smaller than it was pre-pandemic. However, today’s jobs data shows that in order to grow the workforce and the economy, Government must address the continuing rise in the number of people who are economically inactive due to long-term illness.

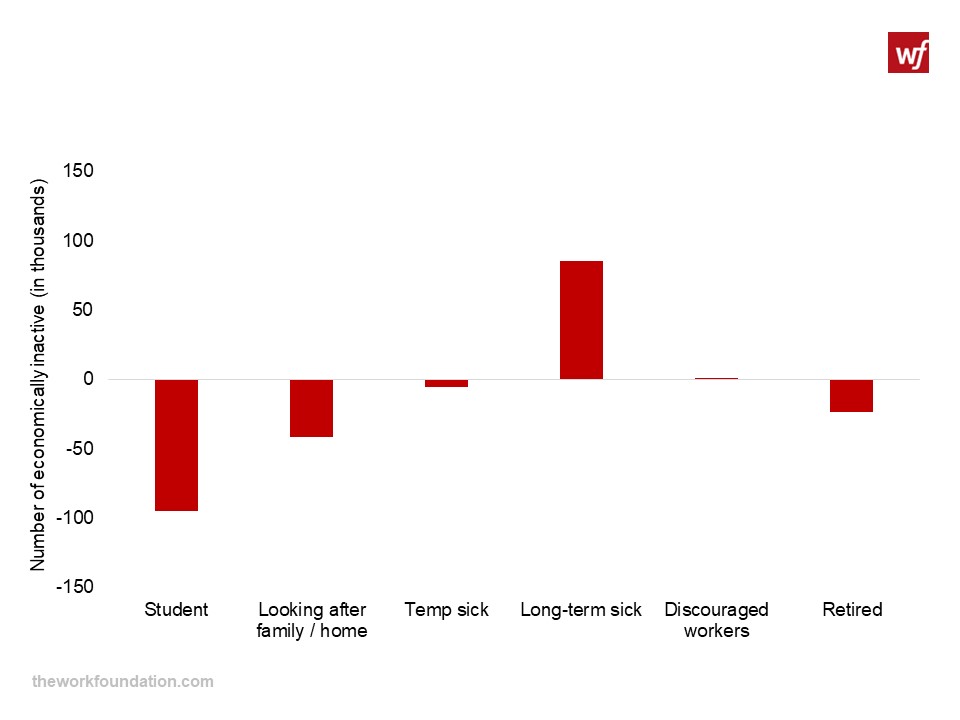

This month’s labour market statistics show that in the three months to March 2023, the number of people who are not in work and not looking for work, or economically inactive, fell by 156,000. However, over this period, economic inactivity related to long-term ill health rose by 86,000 and now stands at a record high of 2.55 million. There has been little movement on the number of 50–64-year-olds who are economically inactive and compose the majority of all those who are out of work and not looking for a job. This is concerning, because it is particularly older workers and those with disabilities or health conditions who face greater barriers to entering and staying in work and may need more specialist support.

Instead of pursuing a punitive approach to getting people back to work from long-term sickness, the Government should look at a radically different approach. This could include investing in a stronger health service, providing more voluntary employment support, stimulating employers to improve job design and encouraging employers to create high-quality, secure jobs.

Long-term sickness is at a record high, but one in five might come back into work with the right support

While inactivity has decreased by 156,000 on the quarter, this was driven by younger workers moving out of full-time education and into the labour market, and inactivity related to ill health has continued to rise.

However, of this group, nearly a quarter, nearly 600,000 people have indicated that they want a job. Given that there are still over a million vacancies, labour demand remains strong and there are opportunities to gain employment in the labour market. With more targeted health and employment support programme, many of the people in this group who want a job could potentially move into work.

The Government should start by reforming employment support within Universal Credit to tackle the complex barriers that prevent people with long-term health conditions from re-joining the labour market.

Change in the number of economically inactive between Oct-Dec 2022 and Jan-March 2023

Source: Work Foundation calculations based on ONS (16th May 2023) Dataset A01 – Table 11: Economic Inactivity for those aged from 16-64 (seasonally adjusted).

To solve the participation puzzle, investment is needed in the NHS, social care and occupational health

The Covid-19 pandemic has put enormous pressure on an already overburdened health system, with a workforce that is earning less in real terms now than a decade ago. Government must urgently invest in the NHS and social care to be able to tackle the wider societal issues that have emerged in the wake of the pandemic, such as long Covid and the increased prevalence of mental health issues, which are keeping so many people out of work.

It’s time to move away from conditionality and expand trials of voluntary specialist employment support for disabled people

We know that around one in five people who are out of work due to long-term ill-health would want a job. The right mix of health- and employment support, coupled with good job design, could enable some of these workers to rejoin the labour market.

As part of its “Back to Work” budget announced this Spring, the Government published a Disability and Health White Paper, outlining new measures to help those with long-term health conditions look for and stay in work. It announced a new voluntary employment scheme for disabled people and those with health conditions. This is a welcome step as the current benefits system categorises disabled people into groups – with some having regular contact with work coaches and risk facing a sanction to their payments if they don’t apply for work, which may not consider the health challenges that they might face, while others are offered no support at all. Many of those with long term conditions will not be in a position to work, but it’s essential that individuals who do want to move towards work have access to information that allows them to opt in to support at the right stage for them.

A more tailored employment support programme should help disabled people and those with long-term health conditions find work that does not negatively impact their health and that will put them on the path to more secure employment. The white paper also announced an expansion of the Access to Work Adjustment Passport trials. Access to Work (AtW) is a government employment support programme that provides funding to employers to make workplace adjustments for their disabled employees. These adjustments include interventions beyond “reasonable adjustments” that would create a more enabling work environment. Currently, disabled workers can only engage with AtW once they find employment and must re-apply for support when they move to another employer. An Access to Work Adjustment passport which details the adjustments that a disabled individual requires and the support they will receive will limit the risk of interruptions in support for people starting a new job. The Government should expand these trials to offer targeted specialist support those who are inactive due to ill-health or a long-term condition and would like to move in to work.

While the voluntary employment support offer and the expansion of the AtW Adjustment Passport trials are welcome steps, the move to strengthen conditionality and sanctions within the benefits system is unlikely to move people with complex barriers back into work. There is limited evidence about the efficacy of intensive conditionality and harsh sanctions on employment outcomes. An even more punitive benefits system might worsen the trust deficit that disabled people have towards the DWP.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed by our bloggers and those providing comments are personal, and may not necessarily reflect the opinions of Lancaster University. Responsibility for the accuracy of any of the information contained within blog posts belongs to the blogger.

Back to blog listing