|

|

|

Contents |

Steven Stich: Autonomous Psychology and the Belief-Desire Thesis

Think of the following theory about beliefs. We have encountered it before, and it may be one you subscribe to.

|

| My brother - in London? |

There are in the brain representations of facts about the world. When you have a belief you have a certain attitude towards such a representation. For example, my belief that my brother is in London involves a representation of the fact that my brother is in London, and I have a certain attitude to it. I won't say any more about this reference to 'attitude. It is just meant to reflect the fact that I could have the representation of the fact in my brain without believing it. That would be having the representation but not the belief-type attitude towards it. With a belief you have the representation and the belief-type attitude.

Suppose on this view I have the belief that my brother is in London, but he isn't. Now there is no fact, my brother's being in London, for a bit of brain to represent. Does this mean that on this view of what a belief is, the belief I have is different from the belief I would have had if my brother had indeed been in London?

Same program, different interpretations

Try another tack.

|

A pc manipulates uninterpreted symbols. It's the user who interprets the output in some way, usually in the light of what interpretation they put on the input.

You input numbers, the program manipulates number sand outputs numbers. You then interpret these.

But in the machine they are uninterpreted symbols.

Numbers, which are crunched according to the program.

You could conceive of the possibility of someone developing a program to predict the likely success of his horse over the next six months. It would take into account its history of success in the past, the pattern of success shown by other horses in the past, the other horses it would be likely to encounter, the strength of these challenges, the weather outlook and likely going at forthcoming meets, and the program would be designed perhaps to mimic as far as possible how a racing expert would factor in these various data to come up with a prediction.

Could you imagine another person unknown to the first working on a quite different problem, the problem of working out how the shares in their company were likely to perform over the next six months. They would talk to expert financial advisers and devise their program so that it did what they did, taking account of a series of factors such as how the shares had performed in the past, what pattern was displayed by shares in general in the past, how rival shares were likely to do and what kind of an impact that would be expected to have, the state of the economy generally and so on.

So two projects going on, one to devise a program to predict the success of a horse, and one to predict the success of shares.

I now ask you to conceive of this possibility: that the two programmers come up with exactly the same program.

In the first

case, when the program has been devised and installed you run it and it draws

a graph on your screen. You interpret this to show its prediction for the success

of the horse. In the second case, I ask you to imagine it coming up with exactly

the same graph, only this time you interpret it as its prediction for the success

of your shares.

In the first

case, when the program has been devised and installed you run it and it draws

a graph on your screen. You interpret this to show its prediction for the success

of the horse. In the second case, I ask you to imagine it coming up with exactly

the same graph, only this time you interpret it as its prediction for the success

of your shares.

I am asking you to conceive of the possibility of this happening, two different problems, but because the two problems turn out to have an identical structure - exactly the same sorts of considerations, exactly the same sorts of data required - the same program being devised in both cases.

"... [I]t is quite possible that two computers, programmed by entirely

different users for entirely different purposes, should happen to run physically

in parallel. They might go through precisely the same sequence of electrical

currents and flipflop settings and yet have their outputs interpreted differently

by their respective users." Lycan, Introduction to Part V, Reader, 2nd

edition, p.253.

This fact has been taken to mean that you can't really attribute beliefs to the PC. What comes up on the screen when the first program is run is a graph which is interpreted to mean 'The horse is going to lose a few races, but then come up smelling of roses'.

What comes

up on the screen when the second program is run is a graph which is interpreted

to mean: "The shares are going to dip before they move firmly ahead."

What comes

up on the screen when the second program is run is a graph which is interpreted

to mean: "The shares are going to dip before they move firmly ahead."

What belief would it be correct to attribute to the pc, the belief about the horse or the belief about the shares?

Remember that the machine is in exactly the same state whether it is outputting the results of the horse program or the results of the shares program.

Does this mean that if you are going to attribute a belief to it when it outputs the graph on either occasion, it had better be the same belief?

This would presumably be ludicrous.

If you are still set on attributing a belief to it, a way out would be to say it's a different belief on the two occasions -in spite of the fact that the machine state is exactly the same on the two occasions...

The conclusion that this supports is that the belief represented in a machine is not fully determined by the state of the machine as it is representing it. The identity of the belief is partly dependent on context.

Representation in the context of people using the machine to work out the future prospects of a horse may be a belief about a horse. Representation in the context of people using the machine to work out the future prospects of some shares may be a belief about shares.

You may think: hurrah! this shows there's something really dodgy about thinking of a machine as having a belief.

So let's switch to human beings.

|

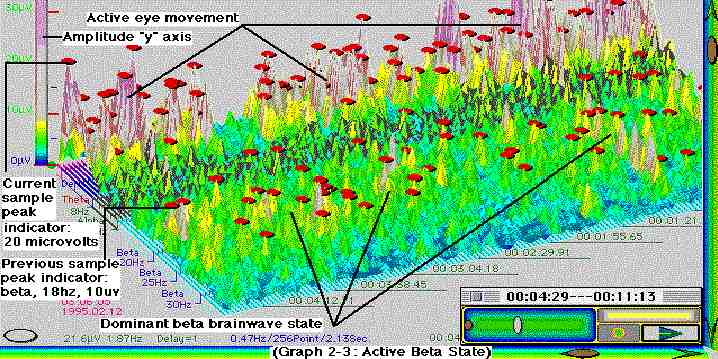

| The ordinary beta brain state, according to Self Study Systems |

Conservatives are often prepared to concede that though beliefs are real mental items, they have a physical basis. For any belief a human being may have there is a physical representation of it in the brain. This is in fact the representational theory of thinking.

|

|

Belief thanks to Sci-Fi

Theme Art |

But if the thought about the PC is correct, though you can say such and such a belief is represented in the brain, you can't tell just by looking at the representation in the brain what the belief was. You would have to know the context in which that representation was held.

This means that representations of beliefs can't play the role in explanation of behaviour which representational theorists assume. If I say saved my money for a few weeks and then began to bet heavily on that fine horse Invincible Spirit, the explanation I might give might be: I did this because I believed that after a dip Invincible Spirit would improve dramatically.

The representationalist would say this is what is happening in consciousness, and what is happening in the brain is that my betting behaviour is being governed by the representation of the belief about the horse's prospects.

But this couldn't be so, because my belief about the horse is not fully determined by the internal sate of the brain. It depends on that, but it also depends on the context in which that brain state occurs.

This means that beliefs cannot be invoked in explanations by the representational theorist.

You cannot both explain what happened by referring to beliefs and by explaining in terms of brain processes. Explanations referring to beliefs refer to context, explanations in terms of brain processes do not.

Put it another way: you can't think of beliefs as 'really' physical states in the brain that can be causally active in governing behaviour, as the Representational theory insists.

Invincible Spirit stars at Haydock: thanks to BBC Sport

Shares pic: thanks to The Depository Trust & Clearing Corporation

Doppleganger pc: thanks to Curtis Seaman

Revised 12:03:03