|

|

|

It is plausible today, isn't it, to think that although we might get all our 'data' through our senses, we might expect that 'data' to need some kind of processing before it is any use to us. The raw data of sense itself is not knowledge, we might think, though it is the basis for knowledge. It needs some kind of pulling together, some kind of structuring perhaps, to turn it into knowledge.

|

Contents |

This is what might sound a reasonable approach today, and Locke's at least sounds quite close to it. One thing that strikes a foreign note however is that he thinks there are two sources of the raw material of knowledge - the senses are one, but introspection, or what he calls 'reflection' is another. Introspection, when you somehow look inside yourself and observe what is 'in' and what is 'going on inside' your mind, is the same sort of thing, this view implies, as sight or hearing, a kind of 'internal' sense. Whether internal or external, it is exclusively our senses, according to Locke, which give us the materials which make knowledge possible.

And in a way, in a very broad sense, knowledge gets to be built by a kind of 'processing' of the raw materials our senses provide.

The data of experience have to be 'reviewed' by reason, and it is this process of reviewing that yields, in some cases, knowledge.

That's the jizz. Let us focus in a little bit, first on the source of all our knowledge in experience.

"Let us suppose the mind to be, as we say, white paper void of all characters, without any ideas. How comes it to be furnished?" [More]

In a famous metaphor, Locke describes the mind of a new-born human being as a writing surface on which nothing has yet been written. It is a 'tabula rasa', Latin for blank tablet or slate. We have at that point in our lives no 'ideas'. But he doesn't mean that we have no processing powers at that stage either. He doesn't mean that our processing powers have to be derived from experience as well. They, he thinks, are in place, part of the constitution of the mind we are born with. To begin with they have no raw materials to work with, but when sense experience begins to flood our minds with 'ideas', our reasoning can get to work.

An alternative view "Reynolds [like Locke] Thinks that Man Learns all that he Knows I say on the Contrary That Man Brings All that he has or Can have Into the World with him. Man is Born Like a Garden ready Planted & Sown This World is too poor to produce one Seed" William Blake Annotations to Reynolds' Discourse VI Thanks to Jennie Tyler 2004-5

|

Let me come back to reason and how Locke thinks it works in a moment. First I should say a little about the ideas that are its raw materials.

| From the horse's mouth: Locke's Essay Book II Chapter I Sections 1-5 |

There are just two ways, says Locke, in which an idea may be acquired: through one or other (or several) of the senses, and through 'introspection' - the mind looking at its own operations.

This is the extremely bold, beautifully simple foundation on which the whole of Locke's account of the workings of the understanding is based.

|

Prompt: Which ideas do you think cannot originate in either of these ways? We had some suggestions in the seminars. Can you recall any that have withstood reflection? |

Much of the Essay - Book II - is taken up with going through a cross-section of our ideas, including the ones on which a good deal appears to depend, and purporting to show how they could plausibly be said to come from one or other of the two sources of ideas that Locke identifies.

From sense come ideas of yellow, white, heat, cold, soft, hard, bitter, sweet.

From reflection come ideas of perception, thinking, doubting, believing, reasoning, knowing, willing.

Sometimes the ideas which we get directly from sense or from reflection compound with each other. We then get complex ideas. Many of our ideas are complex ones. They are made up of ideas that derive directly from sense or reflection, and are themselves derived from sense or reflection in that sense.

You can imagine ideas getting linked together in either of two ways. The first way is on their own, because of the properties they have as individual ideas. The parallel is with atoms of a particular shape such that when jumbled together they lock together. Think of how paper-clips can chain together if shaken up in their box. Atoms shaped like paper-clips would presumably do the same. Chemists often speak of molecules linking up into chains ‘on their own’, because of their shape. Hooks on one molecule get snagged by holes on another and hey presto you have two molecules linked.

The other way is for the mind to play a part in forcing individual ideas together. The mind for Locke is indeed capable of this kind of intervention. It has the power of 'combining several simple ideas into one compound one.' Book II, Chapter XII, Section 1.

(And Locke adds here without qualification: 'and thus all complex ideas are made'. But he also recognises sometimes associations are formed accidentally - without the deliberate intervention of the mind.)

So the mind according to Locke is an agent, an operator upon ideas. In this he differs from some other writers in this tradition of the mechanics of the mind - notably Hume.

And he also differs, more profoundly, and in the opposite direction, as it were, from the Romantics, who thought the mind capable of creating ideas from scratch, and not just from previously existing ideas.

"Locke appears to have regarded association as operative in producing trains of ideas when the synthetic power of the mind was not being exercised. Hume was convinced that the self and its synthetic power were names for nothing but actual connections between ideas..." (Brett's History of Psychology (1st published in 1912-22(3 vols.)) ed. R.S. Peters, rev. ed. London, 1962, p.431) |

|

Pointer forward: Is the mind active? |

What are the elements of Locke's picture of the mind?

The units of 'mentality' are ideas. Just as (Locke believed) the elementary units of material things are atoms ('corpuscles'), so the elementary units of mental things are ideas.

Ideas are for the most part passive, but they do sometimes 'associate' with the reason playing no part (falling into associations by accident.)

Ideas are thought of as within a sort of 'container' - which is the mind itself.

It is not a physical container, of course, but if you have ideas which sometimes associate together (and sometimes don't) the picture is of them being together in a way that is parallel to being spatially together. We, and Locke, speak easily of ideas being 'in' the mind, and this is picturing the mind as a sort of 'container' for ideas. (Because it's not a real physical container, but the equivalent in some way of a physical container, we might speak of a 'quasi' container.) Locke calls the mind a 'cabinet':

Eg: " The senses at first let in particular ideas, and furnish the yet empty cabinet ..." Essay Bk II Ch. 2 Section 15.)

Another model for the mind found in the early Modern period is that of the theatre: "The mind is a kind of theatre, where several perceptions successively make their appearance; pass, re-pass, glide away, and mingle in an infinite variety of postures and situations. " David Hume, A Treatise of Human Nature, Book I, Part IV, Section 6. |

So the mind is a quasi-container for ideas.

But Locke also speaks of the mind as 'perceiving' ideas. And also of the mind manipulating ideas (as we shall see).

What you have in fact is the picture of the mind as a container holding ideas, - and also as containing some kind of perceiver/manipulator of those ideas. Like one of those trucks which have a little hoist mounted on the back to make loading and unloading easier. You may think this isn't a coherent picture at all when you think about it, but it is one we have gone along with for centuries.

Today, we might think of empiricism as the approach based on the tenet that we get all our information about things outside of us - the world around us, including the people there - through our senses: and all our information about things inside ourselves - whatever is in our minds, and whatever is happening there - through introspection or 'reflection'.

Locke of course spoke of 'knowledge' and 'ideas' where I am speaking here of 'information' - so there is the danger of anachronism in my attempt at a gloss.

In his terms, we get the raw materials [not his term] of knowledge through the senses - external and internal. We are aware of these as ideas - elementary ideas, or what he calls 'simple' ideas. To have knowledge it is not enough to have simple ideas, but it is having simple ideas that makes knowledge possible. Complex ideas are formed when simple ideas link up with each other, either 'by accident' or because the mind deliberately puts them together.

Even when we have formed complex ideas however, and have these as well as the simple ideas we are given by our senses - we still don't have knowledge. Knowledge only comes as a result of our minds - using the faculty of reason - scrutinising the ideas we have and noting relationships - Locke's phrase is 'agreements and disagreements' - amongst them. So for example our reason may review our idea of a triangle, and our idea of a straight line too, and 'see' that a triangle must have at least one straight line.

Locke thinks that the extent of our knowledge is very restricted. For knowledge of a thing to be possible, the ideas reviewed by reason have to reflect the essential nature of the subject of the knowledge - the nature, Locke assumes, from which all the properties of a thing necessarily flow. Our ideas of mathematical objects are like this - they do reflect their essential natures. But our ideas of corporeal bodies do not. And therefore, thinks Locke, we cannot have any real knowledge about them.

' I doubt not but if we could discover the figure, size, texture, and motion of the minute constituent parts of any two bodies, we should know without trial several of their operations one upon another; as we do now the properties of a square or a triangle... [but] ...having no ideas of the particular mechanical affections of the minute parts of bodies that are within our view and reach, we are ignorant of their constitutions, powers, and operations...' Essay, Book IV, Chapter III, Sections 25 and 26 |

The reason our ideas of corporeal bodies do not reflect their essential nature is that the corpuscles of which they are made up are too small to be studied. (There is no mystery for Locke about what the essential nature of corporeal bodies is: it is the their corpuscular constitution. The problem is that as human beings we can't get at it. The corpuscles are much too small.) So the ideas we form of a corporeal object can reflect nothing of its essential - corpuscular - nature. We do form ideas of them, but they are just lists of the properties the objects can be observed to have. From such lists we cannot deduce anything for certain.

Nonetheless, we can form some reasonable beliefs about corporeal bodies. And the means of arriving at such beliefs is observation. Studying the natural world empirically yields not knowledge but, in Locke's term, judgement.

'The faculty which God has given man to supply the want of clear and certain knowledge, in cases where that cannot be had, is judgment: whereby the mind takes its ideas to agree or disagree ... without perceiving a demonstrative evidence in the proofs.' Essay, Book IV, Chapter XIV, Section 3

Judgment is still a matter of relationships between ideas - of matter still of ideas' 'agreement or disagreement'; only, in contrast to knowledge, the mind involved in 'judgment' has no clear perception of agreement or disagreement to go on, only an impression of these relationships as though looking at them 'at distance' as it were - (the metaphor Locke uses). (Book IV, Chapter XIV, Section 3).

Elsewhere, Locke explains that sometimes if not always the reason is at work in judgment, and what it does is to assess 'not a certain agreement' between two ideas but 'an usual or likely one'. In a chain of reasoning which falls short of a demonstrative proof several of these assessments of 'usual or likely' agreements will be made, and then in a further step the reason will sum these assessments and deliver a calculation of the likely agreement between premises and conclusion overall. It is this that enables the right judgment to be made:

' The great excellency and use of the judgment is to observe right, and take a true estimate of the force and weight of each probability [that there is agreement between two successive ideas in a chain of reasoning] ; and then casting them up all right together, choose that side which has the overbalance. Essay, Book IV, Chapter XVII, Section 16.

Both knowledge and the opinion that results from the exercise of rational judgement ('probable opinion') are therefore for Locke matters of relationships between ideas. They are the outcome of a review of ideas carried out by our reason.

This summary of Locke's view is expanded and tied to passages in the Essay here.

The raw materials of knowledge are ideas. But, we said, to become knowledge ideas have to be processed. Let's focus for a moment on the picture Locke is presenting here of something 'processing' ideas.

The simplest sort of 'processing' to which Locke thinks ideas are subject is simply that they are 'viewed' by the mind.

This operation may be simple to think of, but it is also very confusing. The question is, who are we to suppose is doing the viewing?

There are ideas, coming into the mind as a result of the functioning of the senses, and there are the ideas created through 'introspection'.

Then there is the thing 'viewing' the ideas, or doing the introspection, the thing that somehow 'sees' the ideas as they exist in the mind, and 'sees' the operations of the mind.

You could caricature this picture by saying that for Locke inside a person is a mind, and inside the mind, 'seeing' the ideas and operating upon them, is - a smaller person.

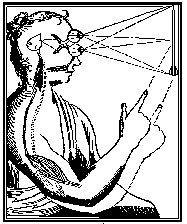

The

conventional diagram of the ‘mechanism’ of seeing has the object yielding

an upside-down image on the back of the retina. But who ‘sees this image?

The problem is very explicit in the diagram from Descartes.

The

conventional diagram of the ‘mechanism’ of seeing has the object yielding

an upside-down image on the back of the retina. But who ‘sees this image?

The problem is very explicit in the diagram from Descartes.

(Notice incidentally that this picture privileges sight. Ideas are 'seen' by the 'inner eye'. Ideas of all modalities are converted into objects of the quasi-sight of the inner eye.)

Critics say that Locke's account of the mind involves a vicious regress. We can spell it out in terms of the account it gives of seeing.

A: What is seeing?

B: Seeing is seeing an idea.

C: Well I can only understand that if you first tell me what seeing is. You have explained seeing in terms of itself, which gets us nowhere (just turns us in a tight circle).

So there is a problem with Locke's notion of 'perceiving' ideas, the simplest bit of processing to which ideas are, he thinks, subject.

Locke himself speaks of reason being a 'faculty'. By faculty he seems to mean something like an agent. It does something. Perhaps he has in mind a part of an organism which does something - the heart, say.

Reason operates on ideas, and in two ways.

These two ways reflect the distinction Locke makes between knowledge and opinion.

Think of a geometrical proof.

E.g. Proof that angles of a triangle sum to the angle you get between two bits of a straight line.

The animation is meant to give you intuitively the realisation that the two angles shown must be identical. It is not itself a proof.

Where you have a chain of propositions on the model of a geometrical proof, you have a conclusion of which you can be certain. But often our conclusions are not like that. They are supported by evidence, or considerations, but not by strict demonstration. For Locke, those conclusions belong to 'probable opinions'. They are probably true, but we cannot be certain about them.

Let me explain a little:

Locke thinks much of our knowledge is got not directly but by a process of 'deduction'. In a deduction, you start with one idea and end up with another, by following a chain of intermediate ideas which are 'linked' in some way. It is reason according to Locke which assesses the character of these links.

If the links between any two ideas in a chain amount to one idea 'agreeing with' another, you have demonstration.

What does he mean by 'agreement' here? He maintains that there is a disagreement at any rate between the idea (a) of a thing existing and (b) of that same thing not existing. And this is why a person who understands the following proposition:

'That it is impossible for the same thing to be and not to be'

will know it to be true. Such a person will perceive a disagreement between the two ideas at play in this proposition and that will be enough for them to conclude with certainty that it is true.

Locke's apparent explanation of the notion of 'disagreement' is expressed like this:

A person 'finds the ideas he has in his mind to agree or disagree, according as the words standing for them are affirmed or denied one of another in the proposition.' Locke's Essay Book I Chapter 2 Section 23

Any geometrical proof says Locke gives us an example of 'demonstration', and the last item in such a chain of agreeing ideas is something you can be certain of.

First, then, Locke says reason tells us the connection there is between successive steps in a demonstration.

There is another kind of chain however, where there are links between ideas, but they are not 'agreements'. Locke calls them 'probable connexions'. A chain of ideas linked by 'probable connexions' has as its final idea something that is probably true: but lacking in certainty. Reason's role in this case is to assess the degree of probability in each of the 'connexions', and synthesize those degrees of probability into an assessment of the probability of the concluding idea.

Second, reason tells us what degree of probability attaches to a step in a proof.

| "For as reason perceives the necessary and indubitable connexion of all the ideas or proofs one to another, in each step of any demonstration that produces knowledge: so it likewise perceives the probable connexion of all the ideas or proofs one to another, in every step of a discourse to which it will think assent due." (An Essay concerning human Understanding, Bk IV, Ch. XVII, Section 2.) |

When you see the table in front of you, Locke thinks you are aware of

| an idea of reflection | the table |

| an innate idea | an idea of sense |

Locke thinks the idea of infinity

| comes from God | comes from a very long way away |

| comes from simple ideas | comes from feeling things very carefully |

END

|

||

Last revised 12:01:05 |

||

A module of the BA Philosophy programme Institute of Environment Philosophy and Public Policy | Lancaster University | e-mail philosophy@lancaster.ac.uk |