I'm Vernon Pratt.

I'm Vernon Pratt.|

Contents

|

Me.

I'm Vernon Pratt.

I'm Vernon Pratt.

Some time ago I wrote a book called Thinking Machines, which discusses the emergence of the modern computer in the 1930s on the basis of previous projects, one to build a mechanical reasoner (Leibniz) and one to build a machine that could work automatically with algebra - thought to be the language in which the laws of the universe had been written (Babbage's Analytical Engine).

Those enterprises, of building machines capable of kinds of thinking, were made possible, I argue, by the rise of the 'representational' conception of thinking, which was a central part of the foundations of the Modern world view that was being laid by the philosophers of the 17th and 18th Centuries.

That is my credential: and also where I come from in my interest in this whole topic.

But the topic is

so interesting you don't really have to explain why it attracts you.

But the topic is

so interesting you don't really have to explain why it attracts you.

It is interesting, that is, once you accept the big picture that something enormous happened in Western culture in the 17th Century - give or take a hundred years or so - and that that enormous thing is still with us.

The enormous thing is the scientific revolution. And the conventional view is that it changed pretty well everything. Before that you had the centuries of medievalism, and before that the Ancient World. The scientific revolution swept away the medieval world and brought in the Modern. On this picture, the Modern world is still with us, stretching from the 17th century to the present moment.

Some people of course speak of 'postmodernism', and argue that at last the world inaugurated by the Scientific Revolution is passing, or has passed, o'er. One of the things you should feel more at home with in the light of what we look at in this course is this postmodern issue, what is at stake and whether we are in fact at a new turning point in our culture, with the framework that has ruled for 3 centuries or more being broken up and something entirely new beginning to take form.

|

Ancient World

|

|

Medieval World

|

|

|

|

Modern World

|

|

Postmodern World

|

Before I leave the big picture, I have to draw your attention to the little matter of the Renaissance.

This comes in between the medieval world and the Modern. It is a sort of line between the two.

But the line is a pretty thick one - so much so that you can take the view that it is not a line at all but a world of its own - a shorter-lived world, but something more than a mere transition from one framework of thought to another.

|

Introduction to the Renaissance, courtesy the WebMuseum, Paris What do you think of Adam Hart-Davis' What the Tudors and Stuarts did for us'? Model webpages backing up the programme offered by the BBC. |

The question is whether you have in the Renaissance a distinctive coherent framework of conceptions, or whether you have only an unstable hodgepodge, some medieval, some Modern, a battle ground rather between old world and new.

The end of the medieval period was marked by a new encounter with the learning of the Ancient World - brought about by it, it is often said. The rediscovery of Greek and Roman culture (to which the name 'Renaissance' - 'Rebirth' - alludes) involved people working with ideas, conceptions, and attitudes which were completely out of kilter with the ones the world for centuries had been familiar with. You may well have encountered the revolutions in architecture or literature or art which marked the end of the medieval world. Other new thoughts for one reason or another came in at the same time: new thoughts about politics, about mathematics, about astronomy, and many more. And there were revolutionary changes in technology, the invention of the printing press, for example. And revolutionary changes in the social order, most spectacularly the emergence of the nation state.

|

... it is impossible to doubt now that the predilection of cultural historians to find the great divide between medieval and modern at the Renaissance has obscured and to some extent misrepresented the true development, not only of Western philosophy, but of Western thought as a whole... it becomes apparent that the most significant point in the development of [both science and philosophy] occurred, not at the Renaissance, but in the early 17th century, in the intellectual turmoil that to some extent caused, and to a large extent was caused by, the thought of Descartes." Roger Scruton, A Short History of Modern Philosophy, London, 1989 edition, Routledge, p.41. |

But none of these revolutions of the Renaissance amounted to modern science. The foundations were laid, presumably must have been, in this extraordinary flowering of culture, but the spectacular rocketing of science associated with the generation of Newton had yet to occur.

So: you can see the Renaissance as a brief but coherent period of its own, or as essentially a transition between one huge configuration, the medieval and another, the Modern.

I always find myself assuming the latter, if only because I find the notions you find in Renaissance writers often alien and difficult. It is much easier to write them off as a hotchpotch than to work out their internal logic and coherence. Francis Bates, The Art of Memory, is very good at the latter.

"[B]oth the philosophical and literary innovations [of the early Modern period] must be seen as parallel manifestations of larger change - that vast transformation of Western civilisation since the Renaissance which has replaced the unified world picture of the middle ages with another very different one - one which presents us, essentially, with a developing but unplanned aggregate of particular individuals having particular experiences at particular times and in particular places." [more ...] |

| Ian Watt, The Rise of the Novel. |

So much for the Renaissance, the medieval world, and the culture of the Ancient World!

It is the Modern one we are interested in, and it came with the scientific revolution of the 17th century.

That revolution entailed the rejigging of the framework within which people lived and thought. New concepts took shape, old ones took new shape. And these are the things - conceptions, ways of thinking, foundational principles - that form the subject matter of the writings we are going to study.

One conception of what the philosophers of the Modern period were (are) doing: coming to terms with the new or reformed concepts the scientific revolution landed culture with: causality (a 'mechanical' universe, not God's book), person (the individual), mind (the inner theatre), substance (what the universe is basically made of), God (in a mechanical universe), knowledge (when there is a gap between the knower and what can be known).

|

'Some years ago I was struck by the large number of falsehoods that I had accepted as true in my childhood, and by the highly doubtful nature of the whole edifice that I had subsequently based on them. I realized that it was necessary, once in the course of my life, to demolish everything completely and start again right from the foundations ... ' Descartes, Meditation I para 1 Cottingham reader, p.17 [The link is to a different translation. Close the window when you are done.] |

|

Web stuff

|

Descartes' proposal was that we ought only to believe those things we had thought about and could be certain of.

He thought 'we' had a very great number of opinions.

He thought of the human mind as a sort of databank stuffed with beliefs and we should make sure they were accurate beliefs.

It makes sense for him to think of a person's knowledge, or set of beliefs, as a pocketful of pebbles. He or she empties the pockets, and turns over each pebble to see if it is nice enough to want to keep. Then throws the blemished ones away.

| Buzz: Is this a project which makes sense today? If it sounds sort of intelligible but unrealistic in some way try and put your finger on why it might seem unrealistic. Discussion site |

Descartes starts off with the thought that beliefs derived directly from the senses would seem to be the ones we can be most sure of.

|

You might notice that of all the senses sight seems to be the most respected. It seems to be the most authoritative sense for our writers in the 17th and 18th centuries, but also you might think that special authority comes through into our own. Martin Jay's Downcast Eyes (Berkeley, 1993, California Press) explores the privileging of the visual that he argues marks the whole of Western culture, from the Greeks onward. |

Eg in my case that I am standing here, in front of you, talking.

Descartes: 'that I am here, sitting by the fire, wearing a winter dressing-gown, holding this piece of paper in my hands, and so on.' Meditation I para 4, Cottingham ed. p.76,7. Veitch translation (Close the text window when you are done)

We still say 'I saw it with my own eyes', 'See for yourself'.

We think of our senses being in certain circumstances the source of absolutely reliable information. You hear people say that they would only believe in ghosts if they actually saw one for themselves.

|

Prompt: My guess is that all of you think I'm here talking to you. As a reminder really, try and draw up a list now of arguments that put this in doubt. |

Philosophers have certainly thought that sense experience was authoritative. G.E. Moore famously attempted to prove the existence of the external world by saying, while he held up his two hands in front of his face: here is one hand and here is another:

|

'I can prove now that two human hands exist. How? By holding up the two hands, and saying, as I make a certain gesture with the right hand, 'Here is one hand', and adding, as I make a certain gesture with the left hand 'and her is the other.' G.E.Moore, 'A Proof of an external world', Philosophical Papers, Macmillan, New York, 1962.  Moore's

paper "A Refutation of Idealism" is online here,

courtesy Andrew Chrucky. Moore's

paper "A Refutation of Idealism" is online here,

courtesy Andrew Chrucky. Pic right courtesy entry for G.E.Moore in xrefer (now a pay site).

|

Bertrand Russell thought you might not be sure you were seeing a brown cow, but you could be sure (sometimes) you were seeing a brown sense- data. Incidentally, Russell begins the first chapter of his wonderful little book Problems of Philosophy with the Cartesian question: 'Is there any knowledge in the world which is so certain that no reasonable man could doubt it?'

So we might think that beliefs based directly on sense are to be retained.

Not so, says Descartes.

For one thing, insane persons are mistaken about what their senses tell them.

They firmly maintain eg

|

' that they are kings when they are paupers, or say that they are dressed in purple when they are naked, or that their heads are made of earthenware, or that they are pumpkins, or made of glass.' First Meditation, Cottingham edition, p.77. Veitch translation (Close the text window when you are done.) |

|

|

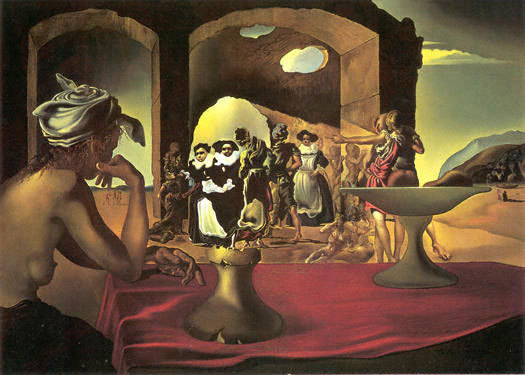

Dali, The Slavemarket , Courtesy the Dali Museum |

Moreover, Descartes continues, we are all taken in by dreams.

In our dreams we have all kinds of beliefs which we accept afterwards are mistaken.

(This is a Western view of dreaming of course. There are cultures who view dreaming as looking through a window into a different reality. The Don Juan books by Castenada tell of such things. Such explorations bring out that when we dream we are in such and such a place doing such and such a thing, we are not forced to see this as a case of false belief, just because our friends see us lying in our bed all the time these experiences took place. We can think of our spirit leaving our body and engaging in various adventures while our body stays put.)

Descartes' main point in discussing dreaming is that it shows beliefs apparently based directly on the senses can be mistaken. But in the course of making it he discusses the conceptual constraints even dreaming is governed by.

He says that though we draw in our dreaming on real sense experience, which we simply reconfigure in various ways, dream experiences are made up of elementary components the reality of which even dreaming doesn't cast doubt upon.

In a similar way, painters composing fictitious scenes use elements that are real enough:

|

' For even when painters try to create sirens or satyrs

with the most extraordinary bodies, they simply jumble up the limbs of

different animals. Or if perhaps they manage to think up something so

new that nothing remotely similar has ever been seen before - something

which is therefore completely factitious and unreal - at least the colours

used in this composition must be real. By similar reasoning, although

these general kinds of things - eyes, head, hands and so on - could be

imaginary, it must at least be admitted that certain other even simpler

and more universal things are real. These are as it were the real colours

from which we form all the images of things, whether true or false, that

occur in our thought.

Veitch

translation (Close the text window when you are done.) |

Descartes appears to be saying that although dreaming undermines the certainty with which we can hold certain beliefs, there are others that it does nothing to undermine.

| Imagining the impossible |

This is because there is a limit to the weirdness of dreaming.

The elements of a dream, he supposes, are drawn from real life. They may be recombined in various odd ways, but the basic elements come from our ordinary experience. In a similar way, a painter often reconfigures bits of the world as we see it, but they are still 'bits' of the real world. (Not sure whether this parallel survives non-figurative art - ?)

If Descartes is right about this, that invariably dreams share some features of waking experience, then any knowledge we have of these features is not undermined by the fact that we dream.

For example, it might be maintained that though we can dream of a world peopled with weird and wonderful things, the things we dream of are things for all that - they are material objects and/or people. We don't dream of worlds in which the notion of an individual material object doesn't apply.

|

Prompt: Or do we? |

Descartes thinks that our knowledge of things 'as things', that's to say our knowledge of those features which belong to them just because they are things is enshrined in arithmetic, geometry, and 'things of this kind'. Two things added to two things makes four things, whatever the particular things may be. Squares have four sides.

So Descartes maintains that the laws of geometry and arithmetic hold in our dreams as in ordinary waking experience:

'For whether I am awake or asleep, two and three added together are five, and a square has no more than four sides.' Meditations 1 paragraph 8. Veitch translation. [Close the window when you are done.]

So our experience of dreaming makes us doubt some things, but leaves the certainty of others intact, including mathematical truths.

Having presented this thought, he proceeds to demolish it. Even mathematical propositions, he says, are subject to doubt:

|

1. 'One reason is that people have made mistakes in reasoning in such matters, and have held as certain and self-evident what we see to be false.' 2. 'A more important reason is that we have been told that God who created us can do all that he desires, and we do not yet know whether he may not have willed to create us in such a way that we shall always be deceived even in the things that we think ourselves to know best. (The Principles of Philosophy, Part I, Section 5, Cottingham p.161.) |

But could we imagine God doing such a thing - ie deceiving us? Perhaps not. But think of this.

Suppose, Descartes says, there is a much more powerful being than us who can make us think anything it wants. Couldn't it be making us think, quite falsely, that mathematical truths are indubitable? Couldn't it be making us think in error right across the board?

A modern variation might be: mightn't evolution have programmed into us some basic 'certainties', because they have not truth but survival value. Maybe 2+2 isn't always 4, but since it is overwhelmingly so in this part of the universe, natural selection would have bred certainty about it into us. -?

This is Descartes' invocation of the Evil Demon:

|

'I will suppose ... that ... some malicious demon of the utmost power and cunning has employed all his [sic] energies in order to deceive me. I shall think that the sky, the earth, colours, shapes, sounds and all external things are merely the delusions of dreams which he has devised to ensnare my judgement.' Meditation I para 12 [Veitch translation. Close the window when you are done.] |

Descartes the writer then draws his first meditation to a close, actually invoking a complicated metaphor drawn, a bit confusingly, from dreaming and waking.

He sums up where he has got to, and suggests the predicament is an awful one. Having started with the reasonable project of getting rid of the rotten apples, getting rid of the blemished pebbles, he has ended up with nothing left. They have all gone. The thought of the Evil Demon has banished certainty altogether, so that if the plan is still to retain just those opinions he could be really sure of, he should retain absolutely nothing.

| A.Immanuel Kant | B.Theophrastus Bombastus Phillippus von Hohenheim - aka Paracelsus. | ||

| C.Isaac Newton | D. George Edward Moore | ||

| A. Discard all your assumptions which when you think about them don't seem very well supported by the evidence | B. Discard everything you can't be sure of | ||

|

C.Discard all your beliefs and start again |

D. Trust the bible | ||

| A. People in another world could not be expected to know maths | B. The possibility of there being an Evil Demon | ||

| C. Insanity | D. Dreaming | ||

| A. We often dream about things that are completely beyond ordinary experience |

B. If you stand nearer a windmill than I do, the two of us will see it differently. |

||

| C. You can work out mathematically that sometimes our sense experience must be wrong. | D. People sometimes report seeing things when we know that they must be mistaken. | Ask a friend | |

END

Last revised 05:03:03