IEP 426: Contested Natures

AWAYMAVE - The Distance Mode of MA in Values and the Environment at Lancaster University

Week 8. GENETIC ENGINEERING

| Tutor Details | Biblio | Assessment | Resources | discussion |

Introduction

This lecture addresses the ontological politics of genetic technologies. The gene operates as a powerful metaphor in contemporary Western societies – signally a sort of fundamental code for life itself. Therefore genetic technologies, by ‘engineering' this basic life-code, signal the total mastery of life itself. For some this rhetoric of mastery confirms the natural human proclivity to enhance natural systems and human performance. For others such technologies contravene fundamental boundaries between the ‘natural' and ‘artificial'. In considering such questions the lecture will introduce contemporary philosophies of life that form a basis for a philosophical and political consideration of such technologies.

Exercise: 8.1:

Exercise: 8.1:

What connotations does genetic engineering have for you? Do these connotations change if we were to talk about genetic ‘modification' or ‘manipulation' rather than ‘engineering'? Why do you think there has been so much public disquiet about genetic technologies?

Refer to the website: http://www.gmcontaminationregister.org/

and look for any GM contamination events around where you live.

Watch a report on GM crops, by Canadian Television (at: http://www.tv.cbc.ca/national/real_video/monsanto.ram ).

What is your reaction to these kinds of genetic modifications?

The Issues

In Enough: Genetic Engineering and the End of Human Nature (2003) Bill McKibben states:

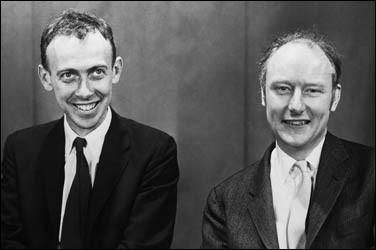

In the spring of 1953, two young academics, James Watson and Francis Crick, published a one-page article in Nature entitled ‘A Structure for Deoxyribose Nucleic Acid.' With it they set off the dynamite whose boom is still reverberating. In fact, the echoes grow louder; what was then theory is now becoming practice, first with plants then with animals, and – oh so close – now with people. ‘Genetics' is not some scary bogeyman. Most of the science that stems from our understanding of DNA is, simply put, marvellous – cancer drugs that target tumours more effectively, for instance, because now we understand much about the genetic makeup of these cells. But one branch of the science that flows down from the discovery of the double helix raises much harder questions. In fact, it raises the possibility that we will engineer ourselves out of existence. (p.7)

For McKibben, the ‘discovery' of DNA by Watson and Crick and their famous Nature article (available at: www.nature.com/nature/dna50/watsoncrick.pdf ) marks both a scientific break-though and a socio-political turning point in modern society. For others Crick and Watson's breakthrough represents one of the defining scientific moments of the twentieth century. Lord Broers, who we listened to in week 6, certainly rated the ‘discovery' of DNA as one of the top-ten achievements in modern science. Indeed, it is almost as if ‘Crick and Watson' and ‘DNA' have a discursive and rhetorical meaning as one of the key scientific discoveries of the last century. They are credited with discovering the ‘secret to life', in the same way that DNA is heralded as holding the basic code for all life and forms of evolutionary hereditary. For example Time Magazine states about Crick and Watson:

For McKibben, the ‘discovery' of DNA by Watson and Crick and their famous Nature article (available at: www.nature.com/nature/dna50/watsoncrick.pdf ) marks both a scientific break-though and a socio-political turning point in modern society. For others Crick and Watson's breakthrough represents one of the defining scientific moments of the twentieth century. Lord Broers, who we listened to in week 6, certainly rated the ‘discovery' of DNA as one of the top-ten achievements in modern science. Indeed, it is almost as if ‘Crick and Watson' and ‘DNA' have a discursive and rhetorical meaning as one of the key scientific discoveries of the last century. They are credited with discovering the ‘secret to life', in the same way that DNA is heralded as holding the basic code for all life and forms of evolutionary hereditary. For example Time Magazine states about Crick and Watson:

On Feb. 28, 1953 , Francis Crick walked into the Eagle pub in Cambridge , England , and, as James Watson later recalled, announced that "we had found the secret of life." Actually, they had. That morning, Watson and Crick had figured out the structure of deoxyribonucleic acid, DNA. And that structure — a "double helix" that can "unzip" to make copies of itself — confirmed suspicions that DNA carries life ' s hereditary information.

Not until decades later, in the age of genetic engineering, would the Promethean power unleashed that day become vivid. But from the beginning, the Watson and Crick story had traces of hubris. As told in Watson's classic memoir, The Double Helix, it was a tale of boundless ambition, impatience with authority and disdain, if not contempt, for received opinion. http://www.time.com/time/time100/scientist/profile/watsoncrick.html

For Time Magazine genes and DNA are all about ‘life'. The significance of Crick and Watson's discovery is that they had found the ‘secret of life'. Despite the scientific caveats that both Crick and Watson would put on this claim, and the technical constraints in exploiting this ‘secret to life' it is this definition of DNA that has become the ‘public image' of DNA. If you Google DNA you get definitions such as:

For Time Magazine genes and DNA are all about ‘life'. The significance of Crick and Watson's discovery is that they had found the ‘secret of life'. Despite the scientific caveats that both Crick and Watson would put on this claim, and the technical constraints in exploiting this ‘secret to life' it is this definition of DNA that has become the ‘public image' of DNA. If you Google DNA you get definitions such as:

DNA: the Instruction Manual for All Life. ( http://www.thetech.org/exhibits/online/genome/ )

A nucleic acid that carries the genetic information in the cell and is capable of self-replication and synthesis of RNA. DNA consists of two long chains of nucleotides twisted into a double helix and joined by hydrogen bonds between the complementary bases adenine and thymine or cytosine and guanine. The sequence of nucleotides determines individual hereditary characteristics . http://www.thefreedictionary.com/DNA , (emphasis added)

DNA is the king of molecules. ( http://www.biology-online.org/dictionary/dna )

At heart then DNA is about life – it is regarded as the ‘key to life', and as an explanation of fundamental processes of reproduction and speciation. What does this mean then for the ‘genetic technologies' that utilise Crick and Watson's discovery? In simple terms, it has resulted in a series of new terms being added to the lexicon – the ‘life science', genetic manipulation, genetic engineering and genetic modification. All of such terms, are about life, and modes of technological modification of life itself. It is the definition of DNA as ‘holding the key' to life that is critical to understanding the wider connotations of such technologies.

Listen for example, James Watson, speaking in 1962 about the properties of life (available at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/bbcfour/audiointerviews/realmedia/crickwatson/crickwatson6.ram ).

In this interview Watson neatly outlines his conception of life. He says that whether something (for example the polio virus) is alive or not is not terribly interesting. He is rather interested in different processes, and ascertaining how a virus works procedurally. When questioned about the ‘vital force' we discussed last week, he is dismissive. He suggests, rather, that life is simply an amalgam of different processes and that, by extension, the key to this process is DNA itself.

It is in this way that genetic technology adopts a mechanistic view of life. Life is simply a product of the raw code, supplied by DNA. As such life is alterable, simply because such processes are knowable and alterable. This mechanistic view of life parallel's the notion of technological mastery, that we discussed in weeks 6 & 7, in which nature becomes a collection of calculable forces. Watson's denial of the ‘vital force' is also an assertion that life is fundamentally, and simply, knowable and as such alterable.

It is in this way that genetic technology adopts a mechanistic view of life. Life is simply a product of the raw code, supplied by DNA. As such life is alterable, simply because such processes are knowable and alterable. This mechanistic view of life parallel's the notion of technological mastery, that we discussed in weeks 6 & 7, in which nature becomes a collection of calculable forces. Watson's denial of the ‘vital force' is also an assertion that life is fundamentally, and simply, knowable and as such alterable.

This mechanistic view of life is deeply problematic for many people, both philosophically (as we have explored in weeks 6 & 7) and practically. At heart, the problem that many have with genetic technologies is that, despite their promise, they are concerned with altering life itself. While it is claimed that Crick and Watson ‘discovered' DNA, for many their achievement is categorically different from other technical achievement. Their achievement did not involve any invention, nor did they make anything novel, but rather they uncovered something natural and pre-existing. For many the fact that genetic technologies are involved in altering ‘naturally existing genes' is deeply troubling.

The crux of the issue is life itself, with proponents of technology pointing the potential benefits of such advances if only contemporary society would let go of existing concepts of ‘nature'. Sandel, for example, says:

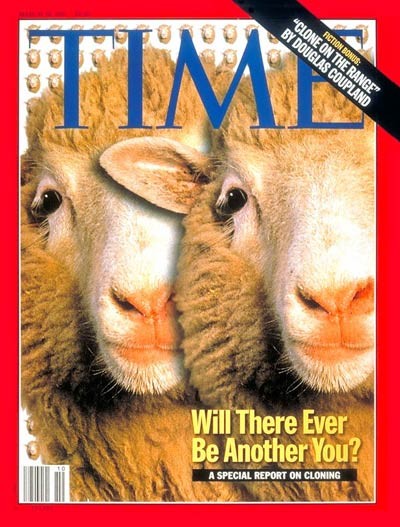

Consider cloning. The birth of Dolly the cloned sheep in 1997, brought a torrent of concern about the prospect of cloned human beings. There are good medical reasons to worry. Most scientists agree that cloning is unsafe, likely to produce offspring with serious abnormalities (Dolly recently died a premature death). But suppose technology improved to the point where clones where at no greater risk than naturally conceived offspring. Would human cloning still be objectionable? Should our hesitation be moral as well as medical? What exactly, is wrong with creating a child who is a genetic twin of one parent, or of an older sibling who has tragically died – or for that matter of an admired scientist, sports star, or celebrity?

Exercise 8.2: the NGO Genewatch defines oulines a number of issues regarding genetic technologies under the headings: ‘GM Crops & Foods', ‘Human Genetics', ‘GM Animals', ‘Lab Use', ‘Patenting' & ‘Bio-Weapons' (see the Genewatch website: http://www.genewatch.org/ )

Exercise 8.2: the NGO Genewatch defines oulines a number of issues regarding genetic technologies under the headings: ‘GM Crops & Foods', ‘Human Genetics', ‘GM Animals', ‘Lab Use', ‘Patenting' & ‘Bio-Weapons' (see the Genewatch website: http://www.genewatch.org/ )

Explore the Genewatch website and think through how each of these concerns is connected to definitions of ‘nature' and ‘life'

Nature and Genetically Modified Organisms

Notions of ‘nature' and ‘life' appear to be at the heart of the ‘idea' of genetic technology – both for its proponents and detractors. In what follows we consider the resonances of the concept of nature in relation to genetically modified food.

In 1997 authors at IEPPP completed a study into the public perceptions of Genetically Modified foods entitled: Uncertain World: Genetically Modified Organisms and Public Attitudes in Britain .

Please read: Chapter 1 of Bill McKibben's Enough: Genetic Engineering and the End of Human available on the MAVE discussion site

They found that food appears to have become a topic of growing reflection for people in the 1990s. For most people that they interviewed food had got better. Convenience, greater international variety, more choice for vegetarians and the improved ability to assess foods for their ‘healthiness' were regarded as positive changes over the past decade or so. Against this is the erosion of the ‘family meal', concerns about processing, the use of artificial preservatives and colouring agents, and an apparent increase in food health scares. Although some expressed a sense of loss that fresh foods were eaten less, the pressures of busy lives meant that convenience food was inevitable and necessary. Thus, to some extent, people seemed to identify a dilemma: although food had made aspects of life better, there were some prices to pay for this in the form of long-term food risks and animal welfare considerations. For some better off participants the solution to this was more organic and natural foods, but this was not seen as a realistic option for the less well off.

Fewer than half the participants in the study had heard of biotechnology in the context of food. Those that had mentioned products such as Zeneca's genetically modified tomato and the active controversy over Monsanto's genetically modified soybean. The dominant reaction of all the members of the public they interviewed was negative. A range of responses arose:

- that genetic modification constituted ‘meddling' with nature and should be avoided;

- that BSE illustrated the unforeseen hazards which could arise from such meddling;

- that such interference in nature illustrated the extent to which industry, science and technology had permeated into daily life;

- that the supposed benefits were for the commercial interests promoting the technology rather than the consumer; and

- that such developments made them feel wary, suspicious and to wonder ‘why'?.

Such reactions were frequently coupled with a sense of fatalism and resignation. It was ‘unnatural':

It sounds like they're going to do a load more messing about and I don't know why they don't just miss that bit out and hurry up and make 3 pills, breakfast, dinner and tea. We'd all have a lot less to worry about [ironic laughter] . … You get shades of Adolf Hitler , you know, you get the supreme fruit and veg.( North London Non-Working Mothers)

It sounds dangerous and unnatural. … I get the impression that all the food's been meddled with in a laboratory before it reaches the supermarket. It doesn't interest me at all. It's like all these, you know these fruits that they inject with stuff to keep the apples redder for longer and things. I want food to be fresh, I don't want it to have all this stuff in it. … But that's like scientifically taking natural food and making it unnatural. ( North London Working Mothers)

I think it should just be left alone. I don't think we should mess with nature. Nature was designed for specific reasons. We mess about with it, we've no right. … I don't know, you can mess about too much, can't you? ( North London Working Fathers)

I find the whole concept of genetic engineering scary. It's messing around with nature isn't it? I'm not sure if that's a good or bad thing. …That's it. It's tampering with nature. What damage is it going to do? If they're messing around with nature like that, what damage is it going to do to the environment? In twenty or thirty years time? I mean, maybe you won't be able to grow your own vegetables then. Because of the damage to the ozone layer, or something like that. ( North London ‘Green Consumers')

When I look at it I think oh, they're dabbling with nature, aren't they? You read scientific developments, that jumps out at me, scientific developments. … You think well they're trying to, you know, genetically change things, and all this, well what are they putting in it to genetically change it. ( Lancashire Working Women)

It's like an interference with nature. Although they may say that it will be better, how do you know it is going to be better, because you don't know what they've done to it, do you? So I'd be very untrusting of it really. … I mean anything to do with genetics is frightening, isn't it, really ? [In what way is it frightening to you?] Well because they cannot prove that if it's new, then they haven't had time to do any tests, have they, over a number of years. ( Lancashire Non-Working Mothers)

Well, beer, wine, yogurt and bread have been made for centuries and the main ingredient … is yeast and that is a natural biotechnological product, I presume. When you get down to today, I don't like it. I'll accept that if we've got to feed starving millions in the world, you've got to find some way of producing masses of food cheaply, but at the same time I don't like it because it's a form of interference with nature, and I'm suspicious of any interference with nature. And I think if you're doing mutations or whatever with foods or animals it's only a short step then to justifying it to doing it with humans and I don't like anything that might lead to... I think it's the thin of the wedge in many ways, which has already been breached. ( Lancashire Church Goers)

It doesn't seem natural. ... For man to interfere with the nature of things. I know processes of evolution, everything goes through changes, sometimes for the better, sometimes for the worse, but I'm not sure whether man should play God and change things for the better, for the luker at the end of the day. (Lancashire Risk Takers)

But I also think it can go a bit too far, because a tomato is a tomato really isn't it, and I think that they're trying to do so much, and make food so much better, I think they don't know what they're getting rid of and I think they can tamper too much. … Well I don't think it's right because like it's saying they're changing the actual species, and each species has adapted for its own life, and it isn't fair to change that just so we can see something that looks nicer. ( Lancashire School Girls)

To illustrate how ‘unnatural' interventions may have unforeseen and dangerous long-term consequences, an analogy was often drawn with BSE, when cattle were fed sheep and other mammalian offal. Turning cows into carnivores (and at times cannibals) was seen as unnatural and the effects bad. BSE had demonstrated the power of nature to 'strike back'. Genetic modification sounded like a similar scale of interference with natural processes, leading many people to expect harmful effects in the long-term:

F Well they seem to come up, you hear more and more things, I think you do personally, but everybody's denying what caused BSE and that it's something to do with unnatural processes with animal foods as far as I understand it.

F: Forcing natural herbivores to eat meat.

F: Yes and I just think it's unnatural. Is it good for you?

F: I think we're worried basically about the safety aspects.

( North London Working Mothers)

M: I'm definitely negative. I think if I'd read that before BSE my thoughts might have been more positive, but I think, like John said, I think you have to. Unfortunately we're going the hard way about meddling in things that we don't really understand - Yes, at the end of the day we were feeding meat to herbivores weren't we, so what do we really know about what we're doing here .... I just think we meddle too much and, I don't know, maybe we think that we've tested these things enough but we can never be sure, be sure what the effects are going to be in 5 years, or maybe 10 years time. When do you draw the line at the end of the day? ( Lancashire Risk Takers)

Another response was that biotechnology was too scientific for people to comprehend easily and many wanted to know more about what was involved. There was a feeling that scientific and technical interventions moved food even further from its (desirable) natural state. Although current processed foods were acknowledged not to be ‘natural', further ‘scientific' processing in the form of genetic modification was an intensification of this. Thus some people conceived of genetic modification as a new tier of processing with foods produced in this way being a unwelcome move away from nature (and the land) into science (and the laboratory).

F: Why does science have to come into food?

Mod: Go on, finish the thought.

F: Put myself on the spot now. Food is grown and produced.

F: Fish fingers aren't. Pizzas aren't.

F: Shut up!

Mod: Let her talk.

F: Cheese and things, why does science have to get involved? (I)t's not necessary is it.

( North London Working Mothers)

M: I mean if you look at traditional ones, you're not really changing the composition in the way that is anything natural about it, but now you interfere with what is natural within a product or a species. For what reason, what is the point of messing around with it?

( North London Working Fathers)

A further link was drawn between genetic modification, science and chemicals in food. More science was commonly equated with more chemically contaminated and less natural food. People drew on their experiences of additives and chemicals when they read the concept of biotechnology and linked the two in a negative way: ‘It sounds very technical to me' (North London Working Mothers); ‘It makes me think of chemicals' (Lancashire Non-Working Mothers); ‘ I automatically think of artificiality' (Lancashire Church Goers).

However, having to eat genetically modified foods was viewed as inevitable and by some individuals as already history. A number expected they were already eating such foods unwittingly. And even though genetic modification was identified as a further development in the history of ‘meddling' with nature, it was also seen as starkly different to past developments in food processing. Genetic modification was seen as changing foods in ways which are irreversible, fundamental, and not possible through traditional preparation techniques in the home which convenience foods replicate. This ‘newness' and unnaturalness raised moral concerns over our human rights to restructure the foundations of life as we know it. Most people had considerable difficulty articulating such concerns, so they were often latent and disguised in the exchanges that took place:

F: I was just thinking though about, like the food that's in the supermarkets now, the pre- processed or pre- .. you know, so you don't have to do all the fiddly bits yourself, but I don't think of it as being scientific. I mean you're transferring [genes] ... I think that's something completely different.

F: It's like pre- processed isn't it, so they've cooked it for you.

F: They've done things you would do to it.

F: And they've peeled and cored things, like you would have done, its not actually scientific, they're not doing anything particularly scientific.

Mod: So what's totally different here, why is this suddenly totally different?

F: Because they're talking about transferring genes.

F: Basic ingredients isn't it.

F: What are they trying to do, are they trying to put sort of animal genes, mix sort of 2 sorts of animals.

F: And plants.

F: Or mix sort of 2 sorts of plants.

F: Animal or plants.

F: You don't, like, we have pets, we have babies but we don't mix their genes.

( North London Working Mothers)

Another common response to the concept board was to demand to know WHY this was being done. Genetic modification was seen by some as a morally contentious act which needed serious justification. Increasing profit was for many people not a sufficiently good argument for such intervention. There was almost no support for claims for ‘improved shelf life', ‘appearance', ‘flavour or ease of processing', as these justifications seemed to be seen as trivial or insufficient for meddling with foods which were generally viewed as basically fine:

F: Food is all right as it is. … We're not sure if it's for our benefit or the manufacturers benefit.

Mod: So the question it raises for you is for whose benefit?

F: Yes I think so. Because it says there, … perhaps the increase in flavour might be of benefit [to us] but the other things are of no importance. I don't care what it looks like and I don't care how long it's on the shelf for.

F: The rest of it … they're adding something to it to make it taste different to what it should taste like.

Mod: Do you not think that all this is to actually improve life for consumers?

F: It doesn't sound like it.

F: I think that's how they will project things, but I think the problem is that the trust has gone anyway, generally speaking, I mean, we've had so many things that we've all eaten for years and then they've told you ‘don't eat this,' and then 2 years down the line say ‘well actually you ought to still have a bit of it'. I think the trust has gone.

F: But all these foods; they are messing around with them. It's them that's causing the problem, not the food.

( North London Non-Working Mothers)

F: Well what's wrong with how things have been for years and years; what's wrong with a tomato, or what's wrong with the banana, what's you know...

F: Maybe if you can give like some, if you can do it and its going to improve, and you can give cold hard evidence that it's not going to harm you, there's no funny drugs been put in it, there's nothing that's going to cause some disease or something twenty years down the line, then yea. But how can they, how can they say what's going to happen twenty years down the line.

Mod: And how can they say that?

F: Well they can't, can they? They've got to guinea pig people aren't they, and is it worth... I don't know, it's just to me, it's scientific developments jumped out. And I know science has got to move on and everything, but it always makes you a bit dubious I think.

F: Scary …

F: My first reaction when I read it was, why do we need to bother with that? I mean there has to be some advantage for the customer for something like this to be brought in, and for me in terms of improving shelf life and appearance, flavour I don't think it's necessary.

( Lancashire Working Women)

M: I can only really echo what these have said, other than there's a saying that ‘if it isn't broke, don't bother trying to fix it', and there's nothing wrong with food as it is naturally except that it hasn't got a long shelf life. So really I can see pound signs all over that, that sentence up there, that's all it's really to do with.

M: Yes, well that's all that is all about really, isn't it, to make food last longer so that we don't have to throw away so much at the end of the day, … being preserved for longer.

Mod: It says here in terms of shelf life, appearance, flavour and ease of processing ...[referring to concept board]

M: Appearance is not really important. …

M: The thing as well, you wouldn't be sure that ease of processing, that we'd actually see a benefit of that. It's the processors that would benefit.

M: Price wouldn't come down would it.

M: No it won't. Probably is about lucre, but it's a lot more money in other people's pockets.

( Lancashire Risk Takers)

By contrast, a minority of individuals welcomed the potential application of genetic modification as a positive response to demands for more food. Genetic modification was seen as having considerable potential for helping solve problems of world hunger in the face of mounting population pressures, especially in the Third World . But, with a few exceptions, such potential benefits were viewed as unlikely in the current financially-driven commercial climate:

M: I tend to think that most people are reluctant to change. ... and anything which comes on the horizon it's usually put down as let's stay as we are, things in the past have been better. In a world where the population is expanding at a high rate you've got to, in all areas, be as efficient and use technology in the most efficient manner, and in this respect, although I'm not particularly happy perhaps with choosing that food myself, I think it's something which has to progress to help everybody, or at least to test whether or not the results would be beneficial to help everybody.

Mod: Right, so we have to go down this path?

M: We have to explore it and then to determine whether it was worth-while.

M: Yes, that's what I see, the experimentation. I think we've got, if we were to leave it, you know, and as [Anne] was saying, you know, if we want to leave it and not to tamper with foods and everything, you know, when you look at the world as it is, we'd never be able to feed the world. And I think it's looking at the Third World countries and everything, you know, and the only way we can do that is by experiment. And I think, I'm a big believer in ‘it's every person to his own trade', whatever you call it, it's every person to his own, his skill and everything and I think you've got to trust... It's like when you go to the doctor. You trust your doctor exactly what he's says to you and what he gives you everything. So we've got to trust these biotechnicians with the experiments and doing our changes and I'm sure it is for the best. …

M: I don't believe that farmers are necessarily thinking about the Third World .

F: No, I don't. ( Lancashire Church Goers).

Overall, however, people's immediate responses to genetically modified foods, outside the context of particular products, tended to reflect unease and questioning of intentions. Analogies were drawn with other experiences of food and the risks of genetically modified foods were expected to be analogous in character to those brought about by chemicals and industrial systems of food production - additives and BSE being the most commonly used examples to illustrate the reasoning behind reactions.

Exercise 8.3:

Exercise 8.3:

Think through your own reactions to genetically modified technologies. What are the resonances with analogous technologies that come to mind? How do your reactions change for different types of genetic technology – GM food, stem cell research, cloning etc? How does the concept of nature figure in how you assess such technologies?

Bio-politics

If, as we saw above genetic technologies are the subject of a various set of public perceptions, this means that such technologies are fundamentally political. Decisions about how to support such technologies and how to integrate them into everyday life are essentially political decisions. Rabinow presents a post-structuralist reading of genetic technology that draws on the work of Foucault (introduced in week 6), and seeks to analysis the intersection between political power and genetic technology. Rabinow draws the Foucault's suggestive concept of ‘bio-power'. Rose (2001), summaries bio-power as:

The biological existence of human beings has become political in novel ways. The object, target and stake of this new ‘vital' politics are human life itself. How might we analyse it? I would like to start from a well known remark by Michel Foucault, in the first volume of The History of Sexuality : ‘ For millennia man remained what he was for Aristotle: a living being with the additional capacity for political existence; modern man is an animal whose politics calls his existence as a living being into question' (Foucault, 1979: 188). Foucault's thesis, as is well known, was that, in Western societies at least, we lived in a ‘biopolitical' age. Since the 18 th century, political power has no longer been exercised through the stark choice of allowing life or giving death. Political authorities, in alliance with many others, have taken on the task of the management of life in the name of the well-being of the population as a vital order and of each of its living subjects. Politics now addresses the vital processes of human existence: the size and quality of the population; reproduction and human sexuality; conjugal, parental and familial relations; health and disease; birth and death. Biopolitics was inextricably bound up with the rise of the life sciences, the human sciences, clinical medicine. It has given birth to techniques, technologies, experts and apparatuses for the care and administration of the life of each and all, from town planning to health services. And it has given a kind of ‘vitalist' character to the existence of individuals as political subjects. (pg. 1) (This article by Rose is a useful resource for those interested in the application of the work of Foucault to contemporary technologies, and is available on the discussion site).

Please read chapter 1 & 2 of Paul Rabinow's French DNA: Trouble in Purgatory available on the discussion site.

Think:

Think:

How is Rabinow's analysis different from McKibben's? Think through how Rabinow's analysis of bio-power helps in conceptualising what is at stake in the politics of genetic engineering.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Foucault, M., 1979: T he History of Sexuality, Volume 1: An Introduction . London : Allen Lane .

Grove-White, R., Macnaghten, P., Mayer, S. & Wynne, B., 1997: Uncertain World: Genetically Modified Organisms, Food and Public Attitudes in Britain . Lancaster University , Lancaster .

Rose, N., 2001: The politics of life itself. Theory, Culture & Society , 18(6), 1-30.

Sandel, M. J., 2004: The case against perfection: What's wrong with designer children, bionic atheletes, and genetic engineering. Atlantic Monthly , April, 2004, 51-62.

Web notes by Mathew Kearnes June 05

| Tutor Details | Biblio | Assessment | Resources | discussion |