IEP 426: Contested Natures

AWAYMAVE - The Distance Mode of MA in Values and the Environment at Lancaster University

Week 6. SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY AND NATURE

| Tutor Details | Biblio | Assessment | Resources | discussion |

Technology: Tekhne vs. Episteme

Craft vs. Knowledge

Introduction

This lecture explores the intersections between science, technology and nature. Tracking a course from classical thought to contemporary philosophies of technology and Science and Technology Studies (STS), this lecture introduces a series of key framing dualisms between ‘making and doing'; ‘craft and skill'; ‘pure and applied science'; and ‘science and technology'. The dualistic framing of science and technology is crucial to the deeply held understanding that the goal of humankind is to achieve mastery over nature through technical systems. By rethinking such notions we will also examine the current contestation of technological modernity and its links with environmental crisis.

Introduction to the Philosophy of Technology

Introduction to the Philosophy of Technology

Broadly defined technology is about making, producing and using artefacts. As such technology operates to transform ‘natural' things into products, machines, devices and processes. Technology is at the heart of the relation between the human species and the natural world(s). The philosophy of technology is, therefore, not solely concerned with the internal epistemic and ontological questions inherent to specific technical disciplines. Rather philosophy of technology – or rather philosophies of technologies – is concerned with fundamental questions about the relation between; humans and the natural world, ‘pure' and ‘applied' knowledge; and design and execution. The different philosophies of technology we will explore this week offer different conceptions of ‘the human' and the ‘natural'.

But first a little light entertainment.

Exercise 6.1 : Watch the two videos, available on the MAVE discussion site, entitled ‘cog' and ‘precision'.

We mustn't think that philosophers of technology have a monopoly on thinking about technology. In fact much of contemporary sociology of technology is about making sense of what technology means in contemporary society. These two video clips, advertisements for the Honda Accord and the Ford Focus, are interesting because of the way in which they express an understanding of what technology is or should be. Indeed there is much work sociological work to suggest that the automobile is the ultimate exemplar of modern technological society, and that car advertising speaks of the subtle meanings of technology in contemporary Western society. The Honda Accord is advertised with the phrase ‘Isn't it nice when things just work'. Similarly, in the satirical commercial for the Ford Focus a flamboyant designer claims; ‘Precision is the most important thing … Nature aspires to perfection, nature achieves perfection'. Both commercials are about precision, control, accuracy. They speak to a kind of human self-image where incredibly complex machines ‘just work'.

Think: how do both of these car commercials position nature, society and technology?

Think: how do both of these car commercials position nature, society and technology?

Please read Chapter 1 &2 of Andrew Feenberg's, Questioning Technology available on the MAVE discussion site.

The Classics

The first of the chapters by Feenburg charts brief history of the philosophy of technology. Like most histories of the philosophy of technology he starts with the classics, and the origin of the word technology in the Greek word tekhne. The word tekhne is commonly translated as ‘art', craft' or ‘skill'. In Classical thought tekhne refers both to the practical work of the carpenter, the artisan and the artist and to a kind of knowledge. In this sense tekhne is the practical know-how of the craftsman and is conceived as distinct from pure knowledge or abstract concepts. Tekhne is a a knowledge built up from experience, particularly of how to work with particular materials in producing artefacts. For Aristotle tekhne is therefore also a certain ‘capacity for action' based on this kind of practical know-how.

It is in the concept of tekhne that we first glimpse the separation between pure and applied knowledge. For Aristotle, though tekhne represented a form of knowledge, and a capacity to act on the basis of such knowledge, such knowledge is distinct from that of science. In Nichomachaen Ethic he states:

What is known scientifically is by necessity. Hence it is eternal; for things that are by unconditional necessity are eternal, and eternal things are indestructible … The state involving reason and concerned with action is different from the state involving reason and concerned with production. Nor is one included in the other; for action is not production, and production is not action.

For Aristotle scientific knowledge is eternal and indestructible. Alternatively craft:

… is concerned with coming to be; and the exercise of the craft is the study of how something that admits of being and not being comes to be, something whose origin is in the producer and not in the product. For a craft is not concerned with things that are by nature, since these have their origin in themselves.

For Aristotle tekhne is not concerned with theoretical or eternal scientific knowledge, but is more practical. The artefact has its ‘origin in the producer' rather than in itself. Objects of craft do not, for Aristotle, exist eternally in their own nature, but are rather produced through the application of this kind of applied technical know-how.

For Aristotle, though he is careful to designate a unique role and place for tekhne, there is a clear hierarchy in his schema. In the Metaphysics he states:

We have said in the Ethics what the difference is between art and science and the other kindred faculties; but the point of our present discussion is this, that all men suppose what is called Wisdom to deal with the first causes and the principles of things; so that, as has been said before, the man of experience is thought to be wiser than the possessors of any sense-perception whatever, the artist wiser than the men of experience, the master worker than the mechanic, and the theoretical kinds of knowledge to be more of the nature of Wisdom than the productive. Clearly Wisdom is knowledge about certain principles and causes.

For Aristotle theoretical, scientific knowledge is ‘more of the nature of wisdom' than practical craft knowledge. For Aristotle, scientific knowledge is both abstract and eternal, whereas tekhne is both specific and a product of experience.

Modernity

It is in this hierarchy that we glimpse a modern conception of the relationship between science and technology. His valorisation of scientific over practical knowledge Aristotle initiated a dualism with direct influence on contemporary thinking, particularly the division between science and technology. The dominant modern view of science and technology is that science is about the ‘discovery' of basic and abstract theoretical knowledge and technology is about the application of such knowledge in contemporary societies in the production of things. It is in this dualism, between that we see the emergence of parallel dualisms between pure and applied knowledge, and between nature and society.

However, we must be careful in attributing such contemporary understandings of technology solely to Aristotle or the classics. Despite Aristotle's hierarchy of knowledge, which positions theoretical knowledge as closer to wisdom, he does grant practical knowledge certain respect. By simply designating it as a category of knowledge he values craft and skill as worthwhile and unique. Indeed, for Aristotle, there is a certain mystique or magic in the production of artefacts that is special. It is as if the knowledge of the craftsman, though not eternal, is distinctive and in some ways even mystical. It is only in the later half of the 17 th century, when Aristotle's dualism is coupled with the scientific method of Galileo, Newton and Descartes, that a truly modern conception of technology emerges. It is then that the magic of craft is removed, and technology becomes simply the application of theoretical knowledge.

A modern conception of technology emerges at this point when it is assumed that technology is simply the application of basic scientific principles to the ‘real world'. In one sense this modern conception of technology, which draws on Aristotle's hierarchy, is deeply ambivalent toward technology. It is assumed what is really interesting – and worth philosophical consideration are the epistemic questions of basic science, particularly mathematics. Technology is simply viewed instrumentally and as philosophically insignificant. Feenburg outlines the philosophical ambivalence toward technology as:

Common sense instrumentalism treated technology as a neutral means, requiring no particular philosophical explanation or justification. So once again it was pushed aside; as an aspect of private life, it was considered irrelevant to basic normative questions.

In this philosophical vacuum technology assumed a taken for granted common sense meaning – that technological innovation was simply the application of theoretical, scientific insights to technical problems in creating new products. An absolute division between science and technology – both practical and ontological – was also assumed.

Yet it is this very ambivalence to technology as philosophically relevant that defines the powerful relations between technology, nature and the material world in modern thinking. The assumption that technology is simply the application of science in the creation of artefacts also entails the assumption that through technology science is applied to or imposed upon raw material. Aristotle's vitalist philosophy retains a sense of magic about tekhne – that there is something skilful and crafty about the work of the artisan. The skill of the craftsman is the skill of working with materials in creating objects and as such Aristotle understand such objects as originating in design and skill of the craftsman and the particular characteristics of the material. For Aristotle, it is impossible for the craftsman to entirely impose his/her will onto a material. With the birth of a modern conception of technology this vitalist magic is banished, as it increasingly is assumed that it is in technological process that abstract designs are simply imposed upon a blank and formless raw material.

Mastery

What is significant is that it is in this period this notion of imposition becomes both a philosophical analysis of how technology works and a rhetorical goal for how technology should work. Bernard Stiegler (1998) expresses this modern conception of technology as mastery:

Technology becomes modern when metaphysics expresses and completes itself as the project of calculative reason with a view to the mastery and possession of nature. (p. 10)

This mastery and possession of nature is both description of how technology works and a rhetorical goal for technical endeavour. Technology has ceased being craft, and has become a project. For the moderns the mission of technology is to bring nature under its mastery and control. A consequent assumption is that human survival is determined by ‘technological innovation' and the perpetual mastery and exploitation of nature. It is through this underlying metaphysics of mastery that we arrive at the modern notion technological determinism.

Exercise 6:2 Listen to the lecture Lord Broers' Reith lecture 'Technology Will Determine the Future of the Human Race' which can be found at http://www.bbc.co.uk/radio4/reith2005/

Exercise 6:2 Listen to the lecture Lord Broers' Reith lecture 'Technology Will Determine the Future of the Human Race' which can be found at http://www.bbc.co.uk/radio4/reith2005/

Go to lecture 1 Technology Will Determine the Future of the Human Race' and then click 'Listen to the Lecture'.

The Reith lecturer Lord Broers, presents a strong image as you listen to the lecture think about how Lord Broers' technological determinism positions nature and the role of technology in transforming it. Think through how Lord Broers' view of technology corresponds to contemporary understanding of technology and the precise way in which technology will determine human survival.

Opposition to Technological Determinism

It is clear though that this philosophy of technological mastery is neither unqualified nor unchallenged practically or philosophically. Indeed Carl Mitchum (1994) states that:

In the background of virtually all science and technology studies there lurks an uneasiness regarding the popular belief in the unqualified moral probity and clarity of the modern technological project. This uneasiness has been nourished not only by philosophical reflection, but also by the common experience of the citizens of technological societies over the past four decades. (p. 1)

He presents a selected chronology of post WWII technological ‘achievements' which include; the first atomic bomb, the partial melt-down of the nuclear reactor at Three Mile Island, the explosion of the Union Carbide plant in Bhopal and the disintegration of the space shuttle Challenger that have fundamentally challenged the modern ‘technological project'.

In what follows we consider some of the post WWII philosophical reactions to the modern technological project.

Dystopian Philosophies of Technology

Heidegger

Much of contemporary philosophical reflection on technology starts with Heidegger, and particularly his collection of essays The Question Concerning Technology. Feenburg positions as the most prominent of a group of ‘substantivist' thinkers who:

… attribute a more than instrumental, a substantive, content to technical mediation. They argue that technology is not neutral, but embodies specific values. Its spread is therefore not innocent. The tools we use shape our way of life in modern societies where technique has become all pervasive. In this situation, means and ends cannot be separated. How we do things determines who and what we are. Technological development transforms what it is to be human. (p. 2.)

A phenomenologist in the tradition of Husserl, Heidegger's primary goal was to think through what it meant to be. Thus for Heidegger, as (philosophical and everyday) life is lived, the epistemic assumption of scientific neutrality no longer remained valid. For Heidegger, science is not a neutral endeavour, but rather a lived practice. He claimed, however, that the assumption of the neutrality of science and technology, forms a dominant philosophical trap of modern society, in which we are ‘chained to technology'. He stated:

Everywhere we remain unfree and chained to technology, whether we passionately affirm or deny it. But we are delivered over to it in the worst possible way when we regard it as something neutral; for this conception of it, to which today we particularly like to pay homage, makes us utterly blind to the essence of technology.

For Heidegger we are trapped in a technological age, in which technology forms the background of our everyday experience. As life is lived, for Heidegger, the ubiquitousness of technology fundamentally challenges what it means to be human. Again he states:

In remains true nonetheless that man in the technological age is, in a particularly striking way, challenged forth into revealing. Such a revealing concerns nature above all, as the chief storehouse of the standing reserve. Accordingly, man's ordering attitude and behaviour display themselves first in the rise of modern physics as an exact science. Modern science's way of representing pursues and entraps nature as a calculable coherence of forces.

Technology as a Form of Social Power

Foucault

Similarly for Foucault technology is not a set of neutral artefacts. Rather, technology is produced through a complex relationship of social and discursive inscription. The effect is produce an image of technology as a product of a specific context and history – that is technology is socially constructed and operates as a form of social power.

Key, for Foucault, is the operation of discourse. In his analysis of institutions of incarceration defines discourse as the organisation of architecture, bodies, spaces and light that produce certain kinds of subjects (the patient, the worker or the prisoner). In this situation discourse is a particular story about bodies, spaces and matters. It is a story that is so ‘real' it is able to effect a material organisation of these things. It is able to create the conditions for knowledge and to discipline both bodies and things into its service.

Foucault is fundamentally interested in the relationship between discourse and its subjects—the things that it both depicts and designates. He is careful to assert the arbitrariness of the relationship between words and images. For example:

But the relation of language to painting is an infinite relation. It is not that words are imperfect, or that, when confronted by the visible, they prove insuperably inadequate. Neither can be reduced to the other's terms: it is in vain that we say what we see; what we see never resides in what we say. And it is vain that we attempt to show, by the use of images, metaphors and similes, what we are saying; the space where they achieve their splendour is not that deployed by our eyes but that defined by the sequential elements of syntax. And the proper name, in this particular context, is merely an artifice… (Foucault, 1970, 9)

In this example Foucault asserts that the relationship between a word and the thing it represents is artificial. There is no natural relationship between the word and the thing. There is however a discursive relationship—an accumulation of texts, stories and meanings—that define the ‘sequential elements of syntax' determining which things belong to which words (and vice versa). In this context, discourse is fundamentally relational. Discourse is always a story about , or a determination of , something else. That is to say, discourse is always directed toward something else. This something else is the thing, the object, or the material. Foucault's understanding of discourse is a careful analysis of the relation between discourses and things. Thus Foucault terms the relation between words and images arbitrary. There can be no ‘natural' referent outside the circular relation between the word and the thing by which to judge the veracity of meaning.

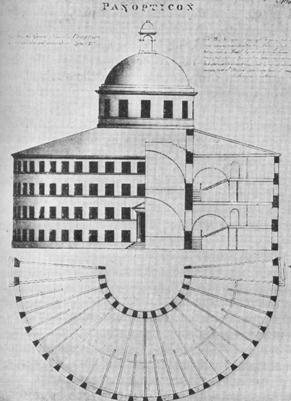

Perhaps the best known of these archetypes is his analysis of Bentham's panopticon. Jeremy Bentham planed a rational prison architecture – the panopticon – by designing a circular prison in which a central observation tower is surrounded by an outer core of cells. For Bentham the key was the visibility of the prisoners and the non-visibility of the observers. Bentham assumed that if the prisoners new that they could be visible at any given time but could not verify whether they were under surveillance that they would modify their own behaviour as if they were under surveillance at all times.

For Foucault Bentham's design is a metaphor for the social construction of technology. Bentham's design was a revolutionary technical advance compared with previous prisons. He thought it possible to utilise the best of modern architecture to create a completely rationale prison through which inmates would regulate their own behaviour and emerge as changed people. For Foucault the technology of the panopticon is imbued both Bentham's technical advances and with socio-cultural understandings of the purpose of prison and the change from the autocratic power of the king to the self-regulating power of surveillance. Bentham's planned prison, based around a play of visibility and invisibility, operates for Foucault as an archetype of the operation of modern power. For example:

The constant division between the normal and the abnormal, to which every individual is subjected, brings us back to our own time, by applying the binary theory of branding and the exile of the leper to quite different objects; the existence of a whole set of techniques and institutions for measuring, supervising and correcting the abnormal brings into play the disciplinary mechanisms to which the fear of the plague gave rise. All the mechanisms of power which, even today, are disposed around the abnormal individual, to brand him and to alter him, are composed of those two from which they distantly derive. Bentham's panopticon is the architectural figure of this composition. (Foucault, 1975b, 200)

In this passage Foucault details the kinds of strategies of incarceration that were made possible by the enlightenment—through the binary division between the normal and the abnormal, the mad and the sane, the prisoner and the free. In this incredible array of divisions and technologies Foucault presents the panopticon then as ‘ the architectural figure' of the entire enlightenment accomplishment. It is as if Foucault's claim is that the total history of the enlightenment—its attempts to separate the good from the bad—is summed up in a single institution. The panopticon thus becomes for Foucault a general formula for the operation of social power. For example:

These disciplines, which the classical age had elaborated in specific relatively enclosed places—barracks, schools, workshops—and where total implementation had been imagined only at a limited and temporal scale of a plague-stricken town, Bentham dreamt of transforming into a network of mechanisms that would be every where and always alert, running through society without interruption in space or in time. The panoptic arrangement provides the formula for this generalisation. (Foucault, 1975, 209)

Technology as Practice

Science and Technology Studies

Law (1994) and Latour (1993; 1999) work, within Actor Network Theory (ANT) is influenced by the Foucault's conception of technology as a discursively constructed. However, they suggest that Foucault's analysis is too rigid, that it leaves no room for alternative readings and denies the active construction discourse. Whereas Foucault suggests that the social construction of discourse is historic ANT scholars suggest that such construction is based in practice. The effect is to produce a more dynamic notion of social construction. For example, Law (1994) states that:

Sometimes it is said that ‘discourse analysis' is so concerned with language and representation that it cannot make sense of hierarchy and inequality. If this complaint is about a writer such as Michel Foucault, then I think that is wrong. This is because Foucault's discourse analysis is concerned not exclusively with language, but with a wide range of different materials. Indeed, it is precisely about how these materials (people, architectures, etc.) perform themselves to generate a series of effects, including those of hierarchy. (emphasis added, p. 25)

Whereas discourse analysis has sometimes been taken as a collapse of the material into the textual, both Law and Latour construct a relational materialist analysis of discourse, emphasising the ordering of physical things in the construction of knowledge. In their analyses of the production of scientific knowledge, both suggest that the modernist presumption of objectivity is practically unachievable. It is not possible for knowledge to be separated from the material situation in which it was produced. Both Law and Latour valorise the materiality of discourse by defining discourse as the ordering of physical objects, things, people and instruments. By focusing on the situatedness of knowledge they are able to propose a relational notion of cognitive processes—emphasising the material constitution of discourse. In the construction of knowledge a series of relations or networks are established between objects and materials. For example:

This is relational materialism … It is that some materials last better than others. And some travel better than others. Voices don't last for long, and they don't travel very far. If ordering depended on voices alone, it would be a very local affair. Bodies travel better than voices and they tend to last longer. But they can only reach so far—and once they are out of your sight you can't be sure that they will do what you've told them. … The argument is that large-scale attempts at ordering or distanciation depend on the creation of what Bruno Latour calls ‘immutable mobiles', material that can be easily carried about and tend to retain their shape. (Law, 1994, 102)

ANT utilises a notion of symmetry to express a way of thinking about things as neither completely ‘social' nor entirely ‘natural'. For ANT, things are hybrids, or quasi-objects—in between the active, determinative capacity of discourse and the faculties of matter. In making this claim ANT articulates a notion of translation that valorises the material situatedness of discourse. In composing a hybrid theory of the thing ANT also rethinks discourse by suggesting that, in defining the object, a series of translations between the discursive and the material are formed. It is not simply that matter and discourse are ‘related', but also that discourse itself is materially located, subject to the movements of translation.

ANT theorists such as Latour, Law and Callon stress the production of scientific discourse under specific conditions and situations. Whereas the deconstructionists position all knowledge as an inter-textual play of meanings, words, texts and images, these authors pursue an analysis of the material contingency of scientific knowledge. Scientific objectivity is a rhetorical ruse not because it fails to escape a hermeneutic intertextuality, but rather because it fails to recognise the way in which the production of knowledge is both individually and materially embodied. For example, both Latour and Law pursue an analysis of the way in which individuals in specific locations and situations produce scientific knowledge. Both compose detailed explorations of the operation of laboratories in suggesting that the scientific assumption of objectivity forces the individual scientist to ignore their own personal embodiment and presence within their ‘results'.

For example, in his extensive study of the Daresbury SERC Laboratory, Law (1994) explores the way in which the formation of scientific and objective knowledge is inextricably tied to the material existence of the subject. In the same way that knowing hypoglycaemia necessitates a fully material appreciation of the embodiment of the illness in the body, scientific knowledge cannot be separated from the situated context of its enactment. This analysis of the formation of (especially scientific) knowledge highlights both the bodily situatedness of the scientist and the many non-human actors involved in this construction (material, instruments, things, plants). Law constructs a careful analysis of the operations, practices and techniques of a specific laboratory. The undertone of his work is that the knowledge produced cannot be divorced from the specific practices, tools, bodies and materials of the laboratory. Latour (1999) suggests that, rather than necessarily attacking the notion of objectivity or the scientific method, the analysis pursued by science studies has attempted to explore the very (human and non-human) objects used in the construction of knowledge. He states that:

If science studies has achieved anything, I thought, surely it has added reality to science, not withdrawn any from it. … Instead of the pale and bloodless objectivity of science, we have all shown, it seemed to me that the many nonhumans mixed into our collective life through laboratory practice have a history, flexibility, culture, blood—in short, all the characteristics that were denied to them by the humanists on the other side of the campus. (p. 3)

Actor network theorists operationalise a notion of translation to express the way in which discourse is formed through the transformation of material bodies into paper, photographs, film, sound and digital impressions (etc). This notion of translation is an acceptance of the ‘reality' of the production of knowledge. It also offers a key insight in the importance of the material embodiment of discourse in this medium. For example, Latour (1990) states that:

… I was struck, in a study of a biology laboratory, by the way in which many aspects of laboratory practice could be ordered by looking not at the scientists' brains (I was forbidden access!), at the cognitive structures (nothing special), nor at the paradigms (the same for thirty years), but at the transformation of rats and chemicals into paper. … Many of the intellectual feats I was asked to admire could be rephrased …as [an] activity of paper, writing and inscription … (p. 22)

Latour demystifies the production of knowledge, emphasising the practical and material embodiment of discourse. He stresses the way in which the production of knowledge is never a solely cognitive or abstract accomplishment, but rather one of paper, writing or inscription. The very term ‘inscription' underscores the physicality of this embodiment. The fact that the production of discourse is (in this instance) a practice of paper writing necessitates that, at the finest level of detail, ink markings be inscribed onto paper.

Exercise 6.3: Read Chapters 15 & 16 of Tim Ingold's The Perception of the Environment: Essays on Livelihood, Dwelling and Skill. Think through how Ingold introduces the classical understanding of craft and his relationship to contemporary philosophies of technology

Exercise 6.3: Read Chapters 15 & 16 of Tim Ingold's The Perception of the Environment: Essays on Livelihood, Dwelling and Skill. Think through how Ingold introduces the classical understanding of craft and his relationship to contemporary philosophies of technology

References:

Foucault, M., 1970: The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences. Vintage Books, New York .

Foucault, M., 1975b: Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Penguin Books, London .

Latour, B., 1993: We Have Never Been Modern. Harvester Wheatsheaf , New York , London

Latour, B., 1999: Pandora's Hope: Essays on the Reality of Science Studies. Harvard University Press, Cambridge and London .

Law, J., 1994: Organizing Modernity. Blackwell, Oxford & Cambridge .

Mitchum, C., 1994: Thinking Through Technology: The Path Between Engineering and Philosophy . Chicago & London , The University of Chicago Press.

Stiegler, B., 1998: Technics and Time 1: The Fault of Epimetheus . Stanford, Stanford University Press.

Web notes by Mathew Kearnes May 2005

| Tutor Details | Biblio | Assessment | Resources | discussion |