IEP 426: Contested Natures

AWAYMAVE - The Distance Mode of MA in Values and the Environment at Lancaster University

Week 2. LANDSCAPE AND NATURE

| Tutor Details | Biblio | Assessment | Resources | discussion |

INTRODUCTION

This week we assess the role of landscape, and of the visual sense, in shaping modern ideas of nature. We assess the primacy of the eye and of visual metaphors in post-Cartesian epistemology, in linear models of perspective, in landscape painting, in the representation of nature on maps, in practices of scientific observation, and in travel from the 17th century. In relation to the particular case of the Lake District, we outline the changing configuration of nature from a discourse of inhospitability and terror to one of beauty and reverence, and how this led to the dual cults of the sublime and the picturesque.

THE PRIMACY OF VISION

In Philosophy

By comparison with other senses, vision has enjoyed exclusive status in the philosophical imagination of Western Culture.

‘Long accounted the “noblest” of the senses, sight traditionally enjoyed a privileged role as the most discriminating and trustworthy of sensual mediators between man and world.’ (Jay, 1986, 176).

The eye, has been, traditionally, divorced from its position in the human body and positioned above mere experience, with a god-like panoptic ability. Indeed, sight and vision are at the core of Western notions of knowledge and understanding. The word ‘idea’ may be traced to the Greek verb ‘to see’ and the notion of ‘outward appearance’. The mental processes of forming ideas, concepts, connections and tangents have enjoyed an extensive visual vocabulary. To see, to perceive, to ‘take it all in’ are, either formally or colloquially, used as metaphors for understanding, cognition and deduction. Epistemologically, knowledge has typically been equated with representations of an external world. Based on the notion of a universal visual experience – that all people ‘see the same world’ and that therefore, the external, physical world is universal, pre-eminent, and foundational – knowledge is judged according to its degree of exactitude in reflecting this external reality.

The particular fascination with the eye as the apparent mirror of nature

and a more general ‘hegemony of vision’ has characterised

western social thought and culture over the past few centuries, some would

argue since Aristotle (Rorty 1980). Such a dominance of the eye, what

Bermingham calls ‘optical truth’, and of its ambiguous consequences,

are part of the process by which subjects are interpolated in the west

(1994). This was the outcome of a number of developments in Europe, including

ecclesiastical architecture of the Mediaeval period which increasingly

allowed large amounts of light to filter through brightly coloured windows;

the growth of heraldry as a complex visual code denoting chivalric identification

and allegiance; the notion of linear perspectivism in the fifteenth century

in which three dimensional space came to be represented on a two-dimensional

plane; the development of the science of optics and the fascination with

the mirror as both object and metaphor; the growth of an increasingly

spectacular legal system characterised by colourful robes and courtrooms;

and the invention of the printing press which reduced the power of the

oral/aural sense.

Sight has been long been regarded as the noblest of the senses, as the

basis of modern epistemology. Arendt neatly summarises the dominant tradition:

‘from the very outset, in formal philosophy, thinking has been thought

of in terms of seeing’ (1978: 110-1). Rorty has famously demonstrated

that post-Cartesian thought has generally privileged mental representations

‘in the mind’s eye’ as mirror reflections of the external

world (1980). He elaborates:

It is pictures rather than propositions, metaphors rather than statements, which determine most of our philosophical convictions ... the story of the domination of the mind of the West by ocular metaphors (Rorty 1980: 12-13).

The dominant conception of philosophy has thus been of the mind as a great mirror which to varying degrees and in terms of different epistemological foundations permit us to ‘see’ nature.

Of course this primacy of the eye is argued in different ways by different philosophers. Descartes’ analysis laid the foundation for modern epistemology by maintaining that it is representations of the external world which constitute the mind. All awareness of the external world is, he says, awareness of internal brain states. But how he asks can people know the world and act towards it when their thoughts are based on awareness of their own body? How do we know that anything which is mental represents anything that is outside the mind? He answers these questions through developing a threefold distinction between the senses: a physical reaction or sensation of a body in contact with other objects; a set of secondary feelings or qualities such as hunger, pain, colour and so on; and a mental grade involving perceptions and judgements of the external world. But perhaps most significant for our argument Descartes conceives of the mind as the inner eye which surveys representations for their fidelity. So there is in Descartes a most complex relationship posited between the many scraps of sensory data which we encounter through our different senses, including that of immediate sensation, and the necessity for these to be translated back from physical codes into mental images, in the mind’s eye. So although sight is the predominant metaphor in modern epistemology, Cartesian thought does not claim that the external world is seen in a wholly unmediated way through the visual sense which produces straightforward representations of that world in the mind.

In Science

There have been intensely complex interconnections between this visualist

discourse and the very discovery of and recording of nature as something

which is separate from human practice. Adler shows that before the eighteenth

century travel to other environments had been largely grounded upon discourse

and especially on the sense of hearing and the stability of oral accounts

of the world (1989). Particularly important was the way in which the ear

had provided scientific legitimacy. But this gradually shifted as eyewitness

observation of nature as the physical world became more important. This

resulted from the gradual working through of the scientific revolutions

of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Observation rather than the

a priori knowledge of mediaeval cosmology increasingly came to be viewed

as the only basis of scientific legitimacy; and this subsequently developed

into the foundation of the scientific method of the west (albeit one in

which such observations would demonstrate one or other religious truth).

Sense-data was typically thought of as that data produced and guaranteed

by the sense of sight. And such sight came to be understood within ‘science’

through what Jenks calls the ‘sanitised methodological form of ‘observation’’

(1995: 3). As Foucault shows in The Order of Things, from the eighteenth

century natural history came to involve the observable structure of the

visible world and not functions and relationships which remain invisible

to our senses (1970). A number of such sciences of ‘visible nature’

developed and these were organised around essentially visual taxonomies,

beginning most famously with Linnaeus in 1735. Such classifications were

based upon the modern episteme of the individual subject, of the seeing

eye and the distinctions that it can make. As Foucault strikingly claims:

‘man is an invention of recent date’, and such a ‘man’

is one who sees, observes and classifies as the notion of resemblance

gives way to that of representation or what Augustine terms the ‘lust

of the eyes’ (1970: 221/312/386).

Such scientific observation came to involve the imposition of a European

system of classification upon the rest of the world. Pratt summarises

the effects of the European-based system of order, what she calls an ‘anti-conquest’:

The (lettered, male, European) eye that held the system could familiarize (‘naturalize’) new sites/sights immediately on contact, by incorporating them into the language of the system (1992: 31).

So scientific observation eliminated the multiple forms of difference between different natures and imposed European-based systems of classifications throughout the world (partly of course because of the claim that such observations were closer to both nature and God).

In Travel

At the same time, the increasing eighteenth century emphasis upon the scientific eye meant that travellers to other countries could not expect that their observations of nature would become part of the scientific or scholarly understanding of that nature. No longer did mere travel to another environment, normally beyond Europe, provide that scientific authority. The first ever international scientific expedition took place in 1735. After that moment mere travel elsewhere did not provide scientific legitimacy for the observations that the travellers made and reported.

The scientific understanding of nature organised through scientific travel and observation thus came to be structurally differentiated from travel as such. The latter required a different discursive justification. And this was increasingly focused around not science but connoisseurship, of being an expert collector of works of art and buildings, of rare and exotic flora and fauna and of imposing and majestic landscapes. In particular, travel became more obviously bound up with the comparative aesthetic evaluation of different natures and less with eyewitness scientific observation. Travel entailed a different kind of vision and hence of a different visual ideology. Adler summarises:

Travellers were less and less expected to record and communicate their emotions in an emotionally detached, impersonal manner. Experiences of beauty and sublimity, sought through the sense of sight, were valued for their spiritual significance to the individuals who cultivated them (1989: 22).

The amused eye increasingly turned to a variety of natures which travellers were able to compare with each other and through which they developed a discourse for what one might term the comparative connoisseurship of nature). Barrell argues that such upper class travellers:

Had experience of more landscapes than one, in more geographical regions than one; and even if they did not travel much, they were accustomed, by their culture, to the notion of mobility, and could easily imagine other landscapes (1972: 63).

Various further developments took place during the course of the later

eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, first in Britain and then throughout

western Europe and North America. These served to constitute the new and

distinctive discourse of the ‘visual consumption of nature’,

which has been so significant for the past century or so. First, there

were huge increases in travelling to various places in England, Scotland

and then Europe, which contained natures which were deemed sufficiently

entertaining for the informed and amused eye. This pattern grew especially

after the highly innovative and influential ‘package tour’

devised by Thomas Cook in 1841. Infrastructures developed which permitted

many environments to become sites for ‘scenic travel’ on a

mass scale (see Ousby 1990, on ruins, natures, literary landscapes and

so on; and Pemble 1987, on the ‘Mediterranean passion’). Especially

important was the railway which involved the subduing of nature and the

new aesthetic of the swiftly passing countryside. Guidebooks, travel maps,

landscape paintings, postcards and snapshots all led to an increasing

visual objectification of an external and consumable nature, one in which

the poor, agricultural labourers and environmental ‘eyesores’

were generally excluded (see Novak 1980, on the aesthetics of painting

of nature in nineteenth century America).

Beginning with Margate in 1815 piers and promenades were built so as to enable ‘promenading’ and the visual appreciation of the sea (see Corbin 1992: 264). New practices developed by which nature was increasingly gazed upon, particularly the practices of leisurely walking both by the sea and over hills and mountains, as well as Alpine and other climbing (see Urry 1995b; Wallace 1993; chapter 6 below).

This increasing hegemony of vision in European societies and its ability to organise the other senses produced a transformation of nature as it was turned into spectacle. Paglia makes this point in dramatic fashion:

There is, I must insist, nothing beautiful in nature. Nature is a primal power, coarse and turbulent. Beauty is our weapon against nature...Beauty halts and freezes the melting flux of nature (1990: 57).

Certainly up to the later eighteenth century nature was generally perceived as hugely inhospitable. Such areas consisted of impenetrable forests, fearsome wild animals, un-scaleable mountains and ravines, hostile demons, unhealthy peasants and appalling odours issuing from the bowels of the earth, especially through the orifices of swamps and marshes. Even those areas of nature which were the first to be turned into the ‘beautiful’ had been regarded as a turbulent power only a few decades earlier. In the early years of the eighteenth century the English Lake District was viewed by Daniel Defoe as ‘the wildest, most barren and frightful’ of any that he had visited. And yet by the end of the century it had become the first such nature tamed for aesthetic consumption; nature turned into spectacle.

Exercise

2.1:

Exercise

2.1:

Think about the objects around now. Perhaps, a pen, a computer, a note book. What are the primary ways in which you experience these objects – do you smell, hear, taste and touch them as well as see them? how do you know that a pen is a pen for example? Is it because of its visual form, for a more complex combination of sensory inputs? How does your experience of them change when you close you eyes?

THE VISUAL CONSTRUCTION OF NATURE

The significance of these ways in which the sense sight has been privileged among the senses with its associations with truth, objectivity and comprehension is the way in which this visual discourse naturalised. This is particularly apparent in the visual depiction of nature with the development of landscape painting, illustration and photography. Robert Romanyshyn (1989) traces the development of modern ‘perspective’ in painting and photography and its influence on depictions and understandings of the natural.

Please read chapter 2 of Romanyshyn's Technology as Symptom and Dream. This is available from the 426 area of the discussion site.

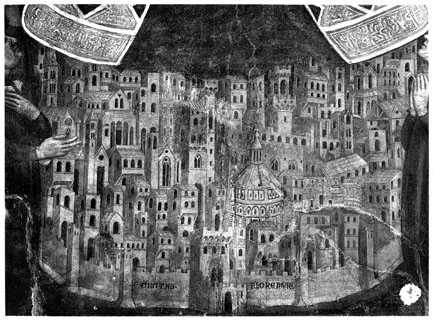

Romanyshyn traces the birth of modern linear perspective to its invention

in 1425 by Filippo Brunelleschi and later codification by Leon Battista

Alberti in his treatise on painting De Pictura. The invention of the linear

perspective is a technical revolution technique whereby painters would

develop a series of projections from a single (vanishing) point (see Plates

1 and 2). Romanyshyn gives two images of Florence that demonstrate the

birth of this single linear perspective. The first depiction, a fresco

by Loggi del Bigallo dating from 1350 (Plate 3), lacks a centralising

visual centre. Rather its depiction of the city includes many perspectival

points, from different horizontal positions and also from above. The image

is chaotic. Buildings viewed simultaneously from different angles seem

to crowd each other. The image also adopts an allegorical tone as two

figures, each side of the city’, seem to boarder the image. The

second depiction (plate 4), dating from 1480 after the invention of the

linear perspective, is much more ordered. The city is viewed from a single,

elevated position, with relative depth, position and height developed

from this single viewing position. The city appears less chaotic, more

rational and indeed it is this imposition of order that signals the roots

of modern map making.

What is significant about the invention of linear perspective is that it represents a new ‘way of seeing’ the world. As Romanyshyn suggests the development of this artistic technique became a cultural vision which has shaped the contemporary technological world. The discourse associated with linear perspective suggests that it is a more accurate way of visually depicting the world. It is however also a particular way of ‘understanding’ the world. Linear perspective is a celebration of the eye of distance, a created convention which not only extends and elaborates the natural power of vision to survey things from afar, but also elevates that power into a method, a way of knowing. With the invention of linear perspective painting itself is transformed. Rather than the chaotic, impressionistic depictions of mediaeval (an earlier) painting modern painting seems to become more realistic, colder and more rational. In the second image of Florence, the figures that bordered the earlier depiction are no longer present. Indeed, all the figures that do appear in the image are objects, viewed in the same way as other buildings, trees and geological features. That is to say that painting, in this period has undergone a radical change. It has become cartographic, and rationalised. Through the application of the single perspective it is assumed that painting may become simply a ‘mirror of the world’.

The parallels here with photography are obviously strong. The invention of the single, linear perspective leads to the transformation of the eye into a technology and a definition of the world to suit the eye. The world becomes knowable through the rational, scalar depictions of maps and charts, graphs and scale drawings, blueprints and diagrams. Panosfky demonstrates the deep connections between the birth of linear perspective with the vanishing point and the development of modern mathematics and physic. Visual depiction therefore becomes a fundamental way in which the world is made knowable and also represents a prerequisite for the mechanisation of life and industry.

It

is in this way that visual depiction becomes irresolutely associated with

truth and accuracy. In the twentieth century the sense of sight and its

power over the other senses has been stunningly changed by what Sontag

calls the promiscuous practices of photography (1979). The visual sensing

of nature has been transformed by the widespread adoption of such novel

discourses. Adam summarises:

It

is in this way that visual depiction becomes irresolutely associated with

truth and accuracy. In the twentieth century the sense of sight and its

power over the other senses has been stunningly changed by what Sontag

calls the promiscuous practices of photography (1979). The visual sensing

of nature has been transformed by the widespread adoption of such novel

discourses. Adam summarises:

The eye of the camera can be seen as the ultimate realisation of that vision: monocular, neutral, detached and disembodied, it views the world at a distance, fixes it with its nature, and separates observer from observed in an absolute way (1995a: 8).

Photography has been enormously significant in democratising various kinds of human experience. As Barthes says, it makes notable whatever is photographed (1981: 34). Photography also gives shape to the very processes of travel so that one’s journey consists of being taken from one ‘good view’ to capture on film, to a series of others. It has also helped to construct a twentieth century sense of what is appropriately aesthetic and what is not worth ‘sightseeing’; it excludes as much as it includes.

The photograph involves an emphasis upon instantaneous results rather than upon process. There is minimisation of performance, compared with other ways in which nature can be represented (such as through music, sketching, painting, singing, sculpting, potting and so on). Ruskin for example considered that the proper seeing of landscape could only come about through sketching or painting and not through anything as instantaneous as composing a photograph. More generally photography produces the extraordinary array of circulating signs and images which constitutes much of the visual culture of the late twentieth century.

Photography has come to enjoy exceptional legitimacy because of its power to present the physical and social world through what appear to be unambiguously accurate modes of representation. Slater notes for example that in the mid-nineteenth century Fox Talbot’s first photography book was entitled The Pencil of Nature (1995: 223). Nature appears to represent itself. Photography came to be characterised as ‘natural magic’.

LANDSCAPE AS A CULTURAL IMAGE

Whilst the invention of linear perspective heralded the radical technical

possibility of transforming a three dimensional scene into a two-dimensional

representation it also naturalised a certain way of understanding such

visual depictions. The eye, indeed the single eye, is regarded as the

centre of the visual world. Cosgrove says that ‘Visual space is

rendered the property of the individual, detached observer’ as a

result of what we have characterised as the possessive gaze (1985: 49;

and see Barrell 1972; Berger 1972; Bryson 1983; Cosgrove 1984; Jay 1993).

In the nineteenth century this conception of landscape as linear perspective

was augmented by romantic conceptions of other natures, of sublime and

barren landscapes in which a more multi-sensual relationship of the individual

to the physical world was to be experienced and represented. In both cases

though what was important was the presumed power relation between viewer/artist

and the viewed/observed. It is the former who have the privileged viewpoint

and power to compose the view and to see the painting. Landscape implies

mastery and possession of the scene and of its representation.

Indeed we should emphasise here that ‘nature’ and ‘landscape’

are not a self-evident set of entities which are simply there, waiting

to be ‘sensed’. Rather as Cosgrove explains, ‘a landscape

is a cultural image, a pictorial way of representing or symbolising surroundings’

(1988, 1). The modern notion of the detached observer, though intimately

connected to notions of mimetic truth, is a ‘cultural idea’.

The linear perspective is, therefore, not a ‘natural’ way

of seeing the world, but rather is one with a deep history and context.

Similarly, ‘landscape’ is not purely natural, but is rather

a ‘cultural idea’ – an accumulation of ways of seeing

the world. Depictions of landscape in painting, illustration and photography

are imbued with subtle cultural ideas of the meaning of natural landscapes.

This is particularly evident in the 19th century depiction of the American

‘wilderness’. Nineteenth century myths of the American wilderness

and its ‘loss’ and fall from innocence were shot through with

religious symbolisms (see Novak 1980). Typical American landscapes were

seen to involve the complex intertwining of God and nature. Nature was

presumed to be something which was viewed through the eyes of an all-seeing

God and not just through the eyes of humans or even of the landscape artists

of the pre-Civil War period. Novak argues that various myths of nature

prevailed - that of nature as primordial Wilderness, as Garden of the

World, as the original Paradise, and as Paradise regained - derived from

Christian theology. Most were based upon two presumptions: that nature

and God were indissoluble, and that there was a realm of human practice

outside and beyond such a nature that was less worthy in God’s eye.

American landscape painting therefore contributed to the social construction

of the American wilderness in these terms. Depictions of these landscapes

operate simultaneously as visual representations of the natural and cultural

metaphors of the American wilderness

In the same way, the representation of the English countryside in landscape painting is imbued with cultural ideas about ‘nature’. Some particularly important ideas, or ways of seeing, landscape in 18th and 19th century landscape painting included:

Gardening

The 18th century saw a massive transformation of British countryside with increasing urbanisation, the growth of market of towns, slavery and mechanical improvements in farming. Ironically at the same time as such transformation ‘landscape’ became an aesthetic and cultural ideal for the middle classes. The ‘natural’ therefore assumed an idealised imaginary at the same time as it transformation and lost. This idealisation was imbued within the Victoria tradition of gardening. The creation of the ‘landscape garden’ went hand in hand with the increasingly instrumentalised production methods in agriculture. The garden became the boundary between lawn and wilder country. As the garden depended on a completely non-functional, non-productive use of land it became an aesthetic expression of Victorian ideals of nature. As the real landscape began to look increasingly artificial, the garden began to look increasingly natural, like the pre-enclosed landscape.

Garden designers were employed to produce new landscapes to surround the houses of the affluent - gardens which were intended to be visually consumed and thereby to convey civilised images of a now-tamed nature (see Pugh 1988, on the eighteenth century garden). Such gardens were viewed as though they were landscape paintings and did not particularly emphasise or develop other senses, especially that of smell (although one can also note the popularity of scented plants and in particular the rose especially from the 19th century). Indeed with the extensive enclosures of the land beyond the garden there was often a continuity of scenery between the garden inside and the tamed nature outside (Bermingham 1986). Much landscape painting showed the owner of the land exhibiting visual mastery over it. Such developments contributed to what we term the ‘possessive’ gaze, which is the new found ability to look at the world as if it could be owned (see also Berger 1972).

The Sublime

Important in such a spectacle-isation of nature were the development of various visual discourses, especially that of the sublime, which enabled the more terrifying aspects of nature to be reinterpreted as part of a meaningful aesthetic experience. This discourse of the visual derived from the writings on aesthetic judgement of Kant and especially in the British context Burke. For the latter the experience of the sublime is one of simultaneous terror and delight; he was particularly concerned with how both these feelings can be physiologically experienced at the same time Burke laid particular emphasis upon how the threatened self would be able to overcome danger through effort, through strenuous action which produces an act of removal from the terrifying threat.

In England such notions of the sublime came to be applied to the subterranean caverns of the Peak District, the Craven region in Yorkshire with its Gothic-like scars and gorges, and then in its most elaborate form to the Lake District (see Ousby 1990). The emphasis in the sublime involved an intense emotional reaction to landscape, to the dizzying claustrophobic fear induced by height, the rapid movement of water and especially overhanging rocks and crags that were seen as immensely threatening to visitors. A bewildering simultaneous mixture of excitement and horror is experienced. The discourse of the sublime includes the widespread use of terms such as desolate, wild, primeval, hideous, frightful, tremendous, and dreadful. Such a discourse helped to make a spectacle out of nature, to attribute value to what had previously been considered repellent about nature, and to further organise the other senses around the visual. Subsequently through the poetry and travel writings of particularly Wordsworth, aspects of the sublime became incorporated into English romanticism, together with some features of the so-called cult of the picturesque.

The Picturesque

During the nineteenth century there was a general growth in viewing nature as picturesque. Though this notion of the picturesque shares some similarities with the sublime, picturesque depictions of landscapes appeal to softer effects of nature - Meandering curve of river, groupings of rocks and trees, interplay of light and shade, subtle gradations of colour. Ruskin as the most significant commentator writing in English claimed that the ‘greatest thing a human soul ever does in this world is to see something ... To see clearly is poetry, prophecy, and religion’ (cited Hibbitts 1994: 257). Nature came to be understood according to Green as scenery, views, and perceptual sensation. He suggests that partly because of the writings of the romantics: ‘Nature has largely to do with leisure and pleasure - tourism, spectacular entertainment, visual refreshment’ (1990: 6). The different discourses of the visual legitimated the turning into spectacle of different ‘natures’: in England, the awesome sublime landscapes of the Lakes; the sleek, well-rounded beautiful landscapes of the Downs; and the picturesque irregular and quaint southern villages full of thatched roofs.

Exercise

2.2:

Exercise

2.2:

Listen to the discussion of the sublime on the BBC’s radio 4 program In Our Time, and think about how, in this discussion, the speakers reproduce cultural understandings of the natural. Think about contemporary equivalents of the sublime and contribute your thoughts on the course discussion site. Programme available at:

http://www.bbc.co.uk/radio4/history/inourtime/inourtime_20040212.shtml

The cultural ideas of landscape inherent in 18th and 19th century gardening and cults of the sublime and picturesque imbue contemporary understandings of landscape. It is almost as if the ‘English Countryside’ is created in this period as areas such as the Lake District, Peak District and North Yorkshire Dales are re-valued at the very same time as radical transformations in these landscapes. As such, the ‘English Countryside’ is not purely natural – it is rather a cultural creation based in particular meanings, stories and narratives of landscape.

THE TEMPORALITY OF LANDSCAPE

Please read Chapter 11 of Ingold's The Perception of the Environment.

For Ingold, the notion that landscape is a cultural production is a problem. He disagrees with the idea that our ‘ideas of nature’ and the history of depicting landscapes actually determine the meaning of natural environments. He states:

The idea that meaning covers over the world, layer upon layer, carries the implication that the way to uncover the most basic level of human beings’ practical involvement with their environments is b y stripping these layers away. In other words, such blanketing metaphors actually serve to create and perpetuate an intellectual space in which human ecology or human geography can flourish, untroubled by any concerns about what the world means to the people who live in it. We can surely learn from the Western Apache, who insist that the stories they tell, far from putting meanings upon the landscape, are intended to allow listeners to place themselves in relation to specific features of the landscape … stories help to open up the world not to cloak it.

For Ingold, the notion that landscapes are solely the product of cultural creation is too strong an analysis. He suggests that such an analysis understates the importance of how such landscapes are actually lived. This is a deep criticism, that goes to the primacy of visual depiction and representation. Ingold suggests that in addition to their visual depiction landscapes are also lived spaces, and that as such the cultural construction of ‘landscape’ is always a relational exercise. Ingold is offering an alternative understanding of the canonical history of depictions of the natural. Whereas, authors such as Cosgrove suggest that landscape is unknowable outside this accumulated, cultural depiction Ingold suggests that such cultural constructions are malleable. The meanings of landscape, for Ingold, operate as temporary stories that open up the natural rather than prohibiting alterative meanings.

Exercise

2.3:

Exercise

2.3:

Think about the proposition made by Ingold about how the cultural ideas we have of landscape work in a temporary and provisional fashion. Think particularly about how this relates to the landscapes that you experience daily – how to the official meanings of these spaces compared with the experience of being in them? On the module discussion site, submit a photograph, picture, drawing or postcard of one of your favourite landscapes and describe what it is about this place that is significant to you.

Web notes by Mathew Kearnes April 2005

| Tutor Details | Biblio | Assessment | Resources | discussion |