IEP 508: Nature in Romantic and European Thought

AWAYMAVE - The Distance Mode of MA in Values and the Environment at Lancaster University

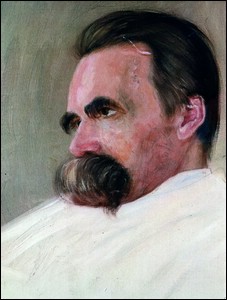

Week 7. Nietzsche

| Tutor Details | Biblio | Assessment | Resources | discussion |

I. Introduction

Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) is, of course, one of the most influential and famous philosophers of all time. He is perhaps best known for his pronouncement that 'God is dead', his theory of the eternal return and of the Ubermensch - the overhuman - (sometimes translated as 'superman') which, infamously, has led to Nietzsche's association with the Nazis who misused his ideas. He is also known for going mad - we won't consider either his madness or the political appropriations of his thought here, as these are not strictly philosophical questions. Our aim here is to see what Nietzsche had to say about nature, putting this in the context of his broader philosophical views.

A note on reading Nietzsche. You will probably find him much easier to read than the other thinkers we have considered so far (except Vogel). But there are disadvantages to this. One is that of being misled into thinking Nietzsche is saying things that are more familiar than they are in fact. That is, the simplicity of his writing can disguise the complexity - and often the extreme strangeness - of his thinking. Another problem is that Nietzsche often writes in aphorisms which can be easily read on their own, but don't obviously add up to any sense of an overall theory or doctrine being put forward. There are divergent views among readers of Nietzsche on the best way to respond to these difficulties. Perhaps the most Nietzschean response is to think that each of us must actively appropriate his aphorisms, forcing a meaning from them, as suits our own concerns. Why this should be the 'Nietzschean' response will hopefully become apparent in the following sections.

II. An Overview of Some of Nietzsche's Key Ideas

Nietzsche is not a systematic thinker in the way that Kant and Hegel are. He advanced different views at different times, and makes no attempt within any of his books to make his various claims consistent with one another. Nonetheless there are some key ideas which tend to recur, or they become prominent at one period in his thought and then get rethought in the context of different ideas later.

Nietzsche wrote a large number of books. Many of these are very influential - in different contexts, different books become the most important or relevant.

The

Birth of Tragedy (1872) - perhaps the major statement of Nietzsche's

aesthetics

The

Birth of Tragedy (1872) - perhaps the major statement of Nietzsche's

aesthetics

Untimely Meditations (1973-5) - includes an important essay on the philosophy of history

Human, all too Human (1876-1880) - the move to an aphoristic style with observations on many themes

The Gay Science (1882) - begins to blend into his next book

Thus Spoke Zarathustra (1883-5) - which Nietzsche saw as his greatest book - written in a pseudo-biblical style, it narrates the thoughts and educative efforts of the character Zarathustra (who is also the historical Zoroaster). Despite Nietzsche's liking for the book, it's usually been less popular with Nietzsche scholars.

Beyond Good and Evil (1886) - the return to aphorisms, particularly focused on the theme of morality, of which Nietzsche is highly critical

On the Genealogy of Morality (1887) - traces the prehistory of western morality, continuing the critical focus of Beyond Good and Evil. Perhaps Nietzsche's most 'systematic' and coherent work, written as a single continuous essay. The major source of his claims in ethics and politics.

The Will to Power. Posthumously published, as a selection from Nietzsche's notebooks put together by his editors supervised by his sister (herself, notoriously, a supporter of the Nazis). This makes the text rather unreliable since it isn't a book Nietzsche himself published, and so some scholars believe it should not be used at all. Others judge that despite its problems it provides an invaluable glimpse into some of the underlying principles of Nietzsche's thought.

So, what are some of the key ideas advanced in these books?

Nihilism

Nietzsche maintains that the modern western world is afflicted by a pervasive nihilism. What is nihilism? This is one of those terms that gets defined differently by different people. Usually, a nihilist might be taken to be someone who:

- denies any absolute moral values or more strongly

- that there is no basis for any moral values at all, and perhaps also

- that nothing can be known or communicated, and that existence is meaningless. The word nihilism first began to appear in the nineteenth century. It derives from the Latin word nihil - nothing (hence the word "annihilate" - to reduce to nothing and destroy utterly).

Nietzsche sees the current of nihilism getting stronger and stronger in western culture. He writes that

"What I relate is the history of the next two centuries. I describe what is coming, what can no longer come differently: the advent of nihilism. . . . For some time now our whole European culture has been moving as toward a catastrophe, with a tortured tension that is growing from decade to decade: restlessly, violently, headlong, like a river that wants to reach the end." (Will to Power)

But what does he mean by this? He doesn't use the word simply to mean that people are rejecting traditional moral values or becoming sceptical about the possibility of knowledge or of finding a meaning in life. He makes two central claims about nihilism:

(1) that 'the highest values devalue themselves' and

(2) that western humanity increasingly opts to will nothingness in preference to not willing at all.

Both of these claims fit into his overall prognosis of the direction of western values. In terms of (1), Nietzsche believes that our moral values have long been grounded on belief in a superior world beyond this world - to which we might progress after death. The idea of this unchanging world, beyond the mundane realm of the senses, has given rise to the ideal of truth (truth as a true insight or description of the 'real' world). But the pursuit of truth generates science, which turns against the belief in the 'real' world as something unjustified. Thus our values devalue themselves - they turn against themselves, corroding their own believability.

(2) For Nietzsche, western humanity has become hopelessly degenerate. Under the weight of centuries of moral codes and social restrictions, most of us can no longer 'will' in any meaningful sense at all. But without something to will, how can anyone keep going? The only solution is to will nothingness - not to pursue any positive goals, but simply to will the destruction of any life and positive goals that might crop up anywhere else.

Nietzsche's diagnosis of nihilism is interesting partly because of how it might relate to the diagnosis of an environmental crisis.

Stop

and think

Stop

and think

You might think here about whether you see any relation between the concept of nihilism and that of environmental destruction/degradation.

Perspectivism

Perspectivism

Perspectivism is another of Nietzsche's ideas. He is critical of the ideal of truth, believing as he does that it rests on a downgrading of the sensuous, perceptible world in favour of the supposedly 'real' world beyond. But then what is the status of his own claims? Doesn't he think they are 'true'? There is no simple answer to this, but certainly Nietzsche wants to return knowing to the body - to see knowing as a bodily activity - and as part of this he stresses that 'there is only a perspectival seeing, only a perspectival knowing'. One can only know from one's particular, embodied, place in the world. Most commentators have therefore made sense of his perspectivism in 2 ways: either

(1) that Nietzsche does still believe in truth, but what can be truly known is this world, known in a bodily-based way;

(2) that Nietzsche denies truth and believes we can only ever gain a multitude of perspectives; nonetheless, the more perspectives we get on any phenomenon, the closer we come to a complete knowledge of it.

The Ubermensch.

Nietzsche's idea of "the overman" (Ubermensch) is very well known, and underlies many of the areas of his thought, although he never explains the idea very fully - rather, he introduces it allusively in the prologue to Thus Spoke Zarathustra. As the name suggests, the overman would be a being who has gone beyond the human - someone who is more than 'human all too human'. Thus, Nietzsche refers to man as being a bridge between animal and Ubermensch. In some way, we need to overcome our own humanity. The Ubermensch is what we would get to, were we to achieve this. Thus Nietzsche states that 'man is something that must be overcome'. These ideas conceal a mass of complexity which we'll come back to later on this page.

The eternal recurrence

This idea also appears in Thus Spoke Zarathustra, among others; it's closely intertwined with Nietzsche's thinking of the Ubermensch. The basic thought is that everything in the universe - indeed, the whole course of the universe - is going to repeat itself again and again, ad infinitum. This repetition will happen in every detail, and consequently every detail of each of our lives will come back again and again - each of us will have to live our lives over and over again, in exactly the same form. There is no end to this process, as Nietzsche conceives it; nor did it have a beginning.

In The Will to Power he explains this as follows: there is a finite amount of matter in the universe, and an infinite amount of time, so in the end all matter is bound to come back into the same combinations that it was in earlier. But there are many problems with this. (1) What's the scientific evidence for it? (2) Why should it matter to me if I keep coming back, since the fact that every detail must recur means I won't be able to remember having had the life before anyway? (3) Since I won't remember any of the previous cycle(s), what justifies Nietzsche in claiming that the one who recurs is still me?

For these and other reasons, most people prefer a different version of the eternal recurrence which Nietzsche sets out in The Gay Science (section 341). Here he imagines someone confronted by a demon who tells them they will have to live their life over and over. He thinks that the right response is to fall to the ground worshipping the demon, having never before heard anything so divine. That is, the right response is to affirm the recurrence of one's life. The advantage here is that one can affirm the recurrence without it needing to really occur. What matters is how you respond to the idea of it occurring, but it doesn't need to be literally true. The demon's words provide a kind of 'test' of one's attitude to life. If you have an affirmative attitude, you will affirm the recurrence. You will be able to affirm even going back again and again through the really awful bits of your life (and by affirm, Nietzsche means not just 'accept' but positively want, endorse, support). Thus, the recurrence is an idea that it is particularly hard to affirm precisely because it entails going over and over these bad bits. If you can even affirm that, then you must have a really affirmative attitude to life - which Nietzsche thinks we should have.

This second version of the recurrence idea is called the 'existential' interpretation, rather than the first which is the 'cosmological' interpretation. The existential interpretation is linked to the idea of the Ubermensch, because Nietzsche believes that being able to affirm the eternal recurrence goes together with being an Ubermensch. To be able to affirm the recurrence is something that only comes about through a struggle, and this struggle is one at the end of which one would have overcome one's humanity. Thus, the propagation of the idea of the recurrence also acts as a necessary condition of people becoming spurred to overcome themselves.

The will to power.

This is among Nietzsche's most controversial ideas, and scholars have given it lots of different interpretations. Sometimes Nietzsche seems to regard it as a metaphysical principle underlying all life: for example, “Granted, finally that one succeeded in explaining our entire instinctual life as the development and ramification of one form of will – as will to power, as is my theory - ; granted that one could trace all organic functions back to this will to power…one would have acquired the right to define all efficient force unequivocally as will-to-power.” (Beyond Good and Evil, p.67). That is, all life would be underlain by will to power as a kind of principle which organises and structures everything. One of the problems with this idea is that it doesn't sit very consistently with Nietzsche's apparent rejection of truth - for isn't the idea that everything is will to power a metaphysical truth-claim of the sort that purports to describe an underlying 'real' world?

One way to get to grips more with this idea is to look at what Nietzsche says about the will to power in nature. Thus, in the next section we will look at Nietzsche's ideas of nature in the context of his theory of will to power; in the following sections we will look more at his ideas on the relation between nature and humanity, both in relation to the concept of the Ubermensch, and in relation to his criticisms of (traditional) morality.

III. The will to power in nature

Nietzsche discusses will to power in nature in his book Will to Power. Given the status of Will to Power as mentioned above, this means that we have to treat what he says here with some caution. Nonetheless, it's worth reading because the discussion occurs in the context of Nietzsche's sketching out of an overarching theory of will to power as the underlying force behind the whole world. As part of this, he explores how will to power manifests itself in nature in particular (that is, non-human nature - he comes on to will to power in humanity in the next section).

Please now read the first extract from Nietzsche for this block 'The Will to Power in Nature'

The text: an overview

(a) Nietzsche discusses mechanism, the idea that the world is made up of atoms of matter in motion.

He criticises this in 2 stages: (1) that mechanism cannot do without belief in forces; (2) that forces themselves must be ultimately understood as manifestations of will to power.

On the first point, his arguments against mechanism are quite obscure, but you can see elements of them in several places. For example, he suggests that one cannot understand how atoms themselves hold together - as single items - without postulating forces through which they cohere. He also suggests that 'laws' of motion do not explain anything - they simply redescribe (note his insistence throughout that science is not genuinely explanatory, that it passes off as explanations what are mere redescriptions of perceptible phenomena in mathematical terms). In order to really explain the behaviour of atoms and the bodies they make up, we need to explain what they do in terms of something within the atoms that makes them engage in this behaviour. For this we have to appeal to forces.

In making these points, Nietzsche is engaging with the science of his time. This recalls Hegel's approach in the Philosophy of Nature. A bit like Hegel, Nietzsche seeks to reinterpret scientific claims so that they fit in with his own metaphysics. He is often drawing on those scientists who are closer to his own views - scientists who have already criticised mechanism.

[There is a good, though quite technical, account of how Nietzsche is drawing on some contemporary scientific discussions of mechanism in Peter Poellner, Nietzsche and Metaphysics (Oxford University Press, 1995), ch. 2. 2. 'atoms and force']

Then (2) Nietzsche thinks forces must be understood to manifest will to power. The more typical idea is that there are just forces as given 'things' within nature - e.g. that nature just contains a 'force of attraction' as one of the entities that make it up. This idea of force, and the belief in atoms as fixed things, are merely projections onto nature of the ways we think about ourselves as human beings. We imagine that when we do actions, there is something within us - some 'will' or 'intention' - that makes us do these actions. Analogously, we suppose that nature is made up of 'atoms' which have 'forces' within them that make them act.

But Nietzsche insists that this way of thinking is fictitious even with respect to humans. When we act, there is no will behind our actions - we just are acting. The acting is fundamental - only retrospectively do we hypothesise that there is some 'will' behind the actions (elsewhere, Nietzsche says that we hypothesise a will in order to claim that people could have acted other than they did so that they can be blamed and punished if what they do is 'evil'). So, for Nietzsche, there is never a 'doer behind the deed' ... just the deed itself.

What is there then in nature? Apparently no atoms, no forces, but only activities. Or, as Nietzsche puts it, 'dynamic quanta, in a relation of tension to all other dynamic quanta: their essence lies in their relation to all other quanta, in their "effect" upon the same. The will to power not a being, not a becoming, but a pathos - the most elemental fact from which a becoming and effecting first emerge' (p. 339). What does this mean? Well, clearly, the passage can be interpreted in several ways, but perhaps as a first stab we could say this: everything that is most basically consists in certain characteristic patterns of action which invariably come into particular sorts of relations with other characteristic patterns of action.

- What does this imply for our general understanding of will to power? - There's no will involved in the ordinary sense (so the phrase is a bit misleading). Rather, the phrase conveys that all things act in certain characteristic ways (this is, in a sense, their 'nature'). Moreover, they desire to persist in their characteristic mode of activity. Again, this isn't because they 'will' to do so, but because they just are that form of activity so they can hardly want to be anything else. In a sense, then, the will to power conveys a kind of process ontology where certain processes, patterns of activity, are the fundamental building-blocks of the world.

(b) Organic life.

Nietzsche then goes on to offer an interpretation of organic life as a manifestation of 'will to power' in the sense just set out. His basic definition of life is this: 'A multiplicity of forces, connected by a common mode of nutrition, we call "life" ' (p. 341). To try to reconstruct what he says systematically:

- some patterns of action are more 'active', forceful, masterful than others. Thus, when the active and the less active come into contact, the weaker patterns will cling to the stronger ones and become incorporated under them.

- when this happens quite a few times a stable hierarchy of patterns of action builds up, and this stable hierarchical structure is what we ordinarily think of as an organism

[so note that for Nietzsche the model of an organism is aristocratic -it consists of relations of dominance and subordination. It's not an egalitarian sort of thing.]

- organisms seek to expand their 'power' by taking over or incorporating other things (hence, hunger).

- if they expand beyond their own powers, then they divide up again into separate entities.

(Nietzsche also includes some criticisms of Darwin.

Exercise

Exercise

Have a think about what he is trying to say about Darwinian evolution here. Are his criticisms on the mark?)

Some general questions which you could consider here:

(a) what is original about Nietzsche's view of nature and organic life? What are the points of contrast and comparison with other views of nature with which you may be familiar?

(b) what, if anything, is appealing about his view of nature?

Web notes by Alison Stone Updated March 2005

| Tutor Details | Biblio | Assessment | Resources | discussion|