IEP 508: Nature in Romantic and European Thought

AWAYMAVE - The Distance Mode of MA in Values and the Environment at Lancaster University

Week 5. Hegel on nature

| Tutor Details | Biblio | Assessment | Resources | discussion |

I.

Hegel: introduction

I.

Hegel: introduction

Hegel is one of the most famous, influential, and difficult of all philosophers. He wrote in the period from 1800-1831, and exerted a decisive influence on – among others – Kierkegaard (and existentialism), Marx and Engels (and therefore Marxism) and Simone de Beauvoir (and therefore feminism). Among Hegel’s most central ideas are: the idea that everything is historical and must be studied in its historical context (including different bodies of knowledge); the idea that everything is ‘dialectical’, which means that it tends to turn into its opposite; the idea that everything is interrelated, or as he puts it that ‘the true is the whole’; and the idea that people only become fully self-conscious through being recognised by other people. Some of his other famous ideas are his account of the struggle for recognition and the ‘master/slave dialectic’; the ‘unhappy consciousness’, the religious person who can’t find happiness in this world; and, in relation to nature, his idea that all of nature in some sense has a ‘mind’, has ‘intelligence’, and that all nature aspires to realise its ‘mindedness’ as fully as it can.

In Hegel’s early work – and above all his book the Phenomenology of Spirit (1807) – he traces the history of different forms of thought and exposes inadequacies in them all which propel human history on an endless progressive course. The mature Hegel (from 1817 onwards) is less interested in history and more in systematically organising all the knowledge we’ve obtained so far. Hegel therefore spent most of his mature life working on an Encyclopaedia of the Philosophical Sciences which put all this knowledge together. He divided it into 3 parts: the logic, the philosophy of nature, and the philosophy of mind. It’s worth noting that the logic is actually not (as you might think) about logic but is about metaphysics – it tries to describe all the most basic features and patterns in the universe.

Hegel’s Philosophy of Nature was first published in 1817 and then revised in 1827 and 1831. Like all the Encyclopaedia Hegel didn’t see it as a finished book but as a set of notes which he used in lecturing – he used to read out the paragraphs from the Encyclopaedia and then explain them orally. So you’ll see when you read the text that for example p. 278 begins with a paragraph (§339). Then there’s a bit that comes after it called Zusatz – this is an ‘addition’, which is where the editors of Hegel’s works added notes that were taken by Hegel’s students while he was giving his oral explanation of what his paragraph meant. Thus the additions aren’t necessarily reliable. It’s best to focus most on what Hegel says in his main paragraphs. (Some of these paragraphs include Remarks – these were added to the text by Hegel himself.)

The Philosophy of Nature hasn’t been studied as much as the rest of Hegel’s Encyclopaedia. This is largely because it’s so obscure. It draws on a lot of material from the sciences of Hegel’s time – material that usually no longer makes much sense. Also, the book uses a lot of technical terms. A good way to make sense of these is to refer to Michael Inwood’s A Hegel Dictionary which (as the title suggests!) explains lots of his technical terms.

II. Background to Hegel's view of nature: "Naturphilosophie"

What was the context in which Hegel developed his thoughts about nature?

The context was one of Germany influenced by the ideas of the German Romantics. As part of their proposal for the 'aestheticisation' of science and culture, the German Romantics put forward the idea that there could be a poetic science, a science that was influenced by and similar to literature. This gave rise to a movement known as Naturphilosophie (literally this means 'philosophy of nature’). This was a scientific movement that tried to study nature in a poetic and philosophically informed way. As well as the Romantics, the other main influence on this movement was the philosopher Schelling, who was a friend and contemporary of Hegel.

Schelling was one of the most important philosophers of the era, though he is now often forgotten and unjustly ignored. It was basically Schelling who came up with the idea of a ‘philosophy of nature’ – his first book on it was Ideas for a Philosophy of Nature (1797) and he went on to write On the World-Soul (1798) and First Sketch of a System of Philosophy of Nature (1799). During and after this time Schelling and Hegel were working closely together. As a result, Hegel went on to develop the original ideas concerning philosophy of nature in a more systematic and rigorous way than Schelling did. Instead, Schelling went through a number of dramatic changes in philosophical position, eventually abandoning the project of philosophy of nature altogether. In contrast, Hegel kept working on it until his death in 1831.

A

large number of influences came to bear on Schelling’s idea for

a philosophy of nature, and these are only just beginning to be explored.

Partly, though, the project is closely connected to German Romanticism

and the wish to re-enchant nature. Schelling thought that a philosophy

of nature could do this by working with a basic conception or interpretation

of nature as unified (on the basis of which experimental research

could be carried out). Schelling sought to interpret all the diverse phenomena

found in nature as exhibiting its fundamental unity.

A

large number of influences came to bear on Schelling’s idea for

a philosophy of nature, and these are only just beginning to be explored.

Partly, though, the project is closely connected to German Romanticism

and the wish to re-enchant nature. Schelling thought that a philosophy

of nature could do this by working with a basic conception or interpretation

of nature as unified (on the basis of which experimental research

could be carried out). Schelling sought to interpret all the diverse phenomena

found in nature as exhibiting its fundamental unity.

He argued that nature’s unity has an inevitable tendency to divide into two halves. Once established, these halves continue to yearn and strain for the unity they have lost – they stand to one another in a dynamic, tense relationship. Thus Schelling defines them as polar forces. He says in On the World-Soul that: ‘It is the first principle of a philosophical theory of nature to start out in the whole of nature from polarity and dualism’. He interpreted all sorts of natural phenomena as exhibiting this polarity – e.g. positive and negative electricity, gravity, magnetism, and chemical processes. But he continued to think that the presence of polarity in these forms showed that natural things strive for their fundamental unity, which remains basic.

It is worth noting that electricity, chemistry, and magnetism were only just starting to be fully studied by scientists at this time. Scientists did not yet have any explanatory frameworks capable of satisfactorily making sense of the many recent discoveries in electricity, magnetism, chemistry and biology. Schelling and Hegel saw all these discoveries as exposing the need for new explanatory frameworks, to be provided by the field of philosophy of nature. Existing science was incapable of explaining these phenomena, they thought, due to the narrowly mechanistic approach it held, which could not accommodate the basic striving for unity that they thought pervaded the electrical, chemical, and biological domains.

However, Schelling did not think that the philosophy of nature should straightforwardly oppose science, i.e. that science should be abandoned and superseded by philosophy of nature. Rather, philosophy of nature was to provide a new and better framework in which scientific research could afterwards be done. So this is, again, the hope for a ‘new science’ – not the mechanistic science of the Enlightenment, but a science informed by the principles of unity and polarity, a science that rediscovers wholeness and vitality in natural things.

A considerable number of scientists took up Schelling’s ideas (Hegel’s versions of those ideas were never so popular). These scientists included, for example, Johann Ritter (1776-1810), who discovered electrochemistry and ultraviolet light, and Hans Christian Ørsted (1777-1851), who discovered electromagnetism. Generally these scientists carried out empirical research informed by Schelling’s idea of nature as structured through a hierarchy of polar forces.

This phase of 'Naturphilosophie' raises some interesting questions. For a while it was the dominant approach within the natural sciences. But around the 1820s there was a new movement in science back to empiricism - to the idea that experimental research should be carried out with as little reliance on theories as possible - one should experiment first and only on that basis generalise to conclusions and theories. This new empiricism became really entrenched and as a result Naturphilosophie came to be seen as a bad thing, a dead end that scientists went down for a while.

Historians of science, though, have defended the philosophy of nature by arguing that really these scientists weren’t doing anything radically different from normal scientists. All scientists have theoretical assumptions, arguably, and the Naturphilosophen had particular theoretical assumptions (in this case stemming from Schelling) that led them to some valuable discoveries. (The philosopher/historian of science Thomas Kuhn famously argued that Schelling’s influence contributed to the discovery of the principle of energy conservation.)

Clearly,

the way Naturphilosophie is seen - as good or bad - depends on

what broader views you hold about the nature of scientific research. At

this point you might like to consider what you think about the idea of

a science informed by philosophical theories about nature. Do you think

that all science is informed by philosophy anyway, even if cientists don't

realise it? Or is it possible to be more empirical, and if so, would a

more empirical be desirable?

Clearly,

the way Naturphilosophie is seen - as good or bad - depends on

what broader views you hold about the nature of scientific research. At

this point you might like to consider what you think about the idea of

a science informed by philosophical theories about nature. Do you think

that all science is informed by philosophy anyway, even if cientists don't

realise it? Or is it possible to be more empirical, and if so, would a

more empirical be desirable?

Further reading/resources on philosophy of nature:

i. See the entry on Naturphilosophie in the Routledge Encyclopaedia of Philosophy

ii. Dietrich von Engelhardt, ‘Romanticism in Germany’ in Romanticism in National Context, ed. Roy Porter and Mikulas Teich (Cambridge University Press 1988)

III . Hegel’s philosophy of nature: an overview

We can now turn to Hegel’s philosophy of nature itself. I'll start with an overview of some of his main concepts - then look at the Introduction and then the section on Organic life.

The main aim of Hegel’s philosophy of nature is to give a theoretical account of the natural world, which he sees as being organised into a hierarchy of stages. He divides the Philosophy of Nature into three main sections, called the ‘Mechanics’, the ‘Physics’, and the ‘Organic Physics’. Each of these three main stages describes a range of natural phenomena, and within that range all these different things are united by a central characteristic.

In

the introduction, Hegel defines the mechanical sphere

as the realm of what he calls ‘singular individual’ beings.

These are material beings which are not structured by any overarching

unity, which don't have any form or organising structure. In this sphere,

he says, the idea has ‘the determination of mutual externality and

of infinite singularisation. Unity of form … is external to this’

(EN §252/1: 217).

In

the introduction, Hegel defines the mechanical sphere

as the realm of what he calls ‘singular individual’ beings.

These are material beings which are not structured by any overarching

unity, which don't have any form or organising structure. In this sphere,

he says, the idea has ‘the determination of mutual externality and

of infinite singularisation. Unity of form … is external to this’

(EN §252/1: 217).

Hegel thinks that the ensuing physical sphere contains beings which are divided: they have structures, but these structures only imperfectly manifest themselves within their material parts. For example, he says that crystals have a structure but this is not properly manifest in the parts of the crystal - although they are organised into a single body, still it seems each part could be split off and maintain an independent existence. So the parts aren't fully integrated into the whole structure.

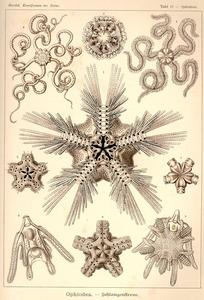

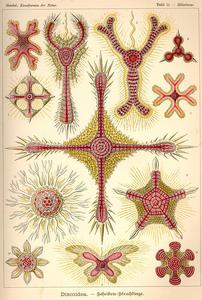

Finally, the organic sphere contains a type of matter that is unified with its structure, unambiguously organised by and reflecting the unity of the whole. That is to say, there is a holistic structure to the living organisms that populate this third sphere. Within these organisms ‘the real differences of form are also brought back to the ideal unity, which has found itself and is for itself’ (§252).

So, broadly, Hegel thinks that nature progresses or develops from a stage in which it consists of matter which is not organised, to matter which is only partly and imperfectly organised, and finally to matter which is fully and manifestly organised. He puts this in more general terms by saying that throughout all of its forms, nature is divided into a material aspect and a conceptual aspect, and these become increasingly unified as nature progresses. The conceptual aspect is the element of unity, wholeness and structure; the material aspect is the element of diversity and lack of integration.

It is crucial to note that when Hegel says that nature has a conceptual aspect, he is using ‘conceptual’ in a way peculiar to himself. Concepts, he believes, are not items that only exist in the human mind. A concept is not just something that we think about. Concepts also exist objectively, independently of whether human thinkers are thinking about them. Hegel says in his Encyclopaedia Logic:

The central message of this paragraph is that throughout the world, there is a structure of forms of thought on which all other beings depend. These forms of thought are not merely ‘subjective’ categories: rather, they objectively exist within the world, independently of human thought about them. Human beings may come to think using categories which have the same content as these objective forms (and when this happens humans are having thoughts that are 'true', thoughts that accurately describe the world’s independent structure). Nonetheless, the independent structure itself is not something that only exists within the human mind. Hegel calls his position ‘idealism’: in the sense that reality is fundamentally made up of, or structured ed by, thought (i.e. ideas).[T]houghts can be called objective thoughts; and among them the forms which are … usually taken to be only forms of conscious thinking have to be counted too. Thus logic coincides with metaphysics, with the science of things grasped in thoughts, which used to be taken to express the essentialities of things. … To say that there is understanding, or reason, in the world is exactly what is contained in the expression ‘objective thought’. This expression is, however, inconvenient precisely because thought is all too commonly used as if it belonged only to spirit, or consciousness, while the objective is used primarily just with reference to what is unspiritual. … [Hence] the logical is to be sought in a system of thought-determinations in which the antithesis between subjective and objective (in its usual meaning) disappears. This meaning of thinking and of its determinations is more precisely expressed by the ancients when they say that nous governs the world. (§24)

The aim of Hegel’s Encyclopaedia as a whole is to describe these objective forms of thought in all the domains where they are present: in the Logic, as the basic forms behind all existence; in the philosophy of nature, as present in nature, and in this case these forms of thought (conceptual structures) are combined with matter in different ways - as nature develops, the forms of thought increasingly pervade and organise matter; and finally in the Philosophy of Mind Hegel looks at how these forms of thought are present in the human mind.

You

could pause here to think about this:

You

could pause here to think about this:

What do you understand by the idea of 'objective thoughts'? Does it make any sense that there could be thoughts existing independently of anyone thinking them?

What might be an example of such an 'objective thought'?

Further reading/resources on Hegel’s philosophy of nature:

i. http://www.gwfhegel.org/Nature/

ii. Stephen Houlgate, ed., Hegel and the Philosophy of Nature (SUNY Press 1998)

iii. Robert Stern, Hegel, Kant and the Structure of the Object (Routledge 1990), ch. 4. Explains how Hegel’s theory of nature anticipates holism.

iv. Alison Stone, Petrified Intelligence: Nature in Hegel's Philosophy (SUNY Press 2004)

Web notes by Alison Stone updated 2005

| Tutor Details | Biblio | Assessment | Resources | discussion|