AwayMave Home Page | IEPPP Home Page | 406 Module Home Page | University Home Page | VP Home Page |

||

|

||

Reason, nature and the human being in the West: Part 3 |

||

AwayMave Home Page | IEPPP Home Page | 406 Module Home Page | University Home Page | VP Home Page |

||

|

||

Reason, nature and the human being in the West: Part 3 |

||

|

Thomas Gainsborough's Mr and Mrs Andrews (about 1748/9) |

The 18th Century is often defined in terms of a philosophical outlook, and there is no shortage of succinct statements of what it is supposed to have believed about human beings and the world they related to.

Contents |

THE 18TH CENTURY WAS SELF-CONSCIOUS ABOUT BELIEFS

This is partly because as a period it was self-conscious about beliefs - how to tell which beliefs were correct, how to enlarge the number of these, and what the importance of true beliefs, namely knowledge, was.

- AND INTERESTED IN KNOWLEDGE AS AN EDIFICE

It was also interested, in a way that was new, in human knowledge as a single edifice. The great Encyclopaedia of the Enlightenment philosophes, one of the monuments of the age, was concerned not only to set forth the sum of human knowledge, which was a not an innovative project, but to display "the order and connection of the parts of human knowledge" (D'Alembert, Preliminary Discourse to Diderot's Encyclopaedia, (first published 1751), Library of Liberal Arts edition, Trans. Richard N. Schwab, 1963, p.4).

|

| D'Alembert (1717-1783) courtesy BibMath |

(We also remember that Modern science was rooted in the exclusion of some material that had counted as knowledge before.)

The main springs of the project were D'Alembert (who was the Editor) and Diderot, contributors included Holbach, Montesquieu, Rousseau and Voltaire - the 'Encyclopedists'. For its anticlerical sentiment it was suppressed by Royal Decree in 1759.

The ruling philosophy also, most happily, placed emphasis not only on being open about beliefs but on expressing them as clearly as possible, so there is the bonus of having what they regarded as knowledge not only set out, but set out as intelligibly as they knew how.

| Condorcet on the Enlightenment |

The 18th Century saw itself, at any rate, as the flowering of the revolution begun in the seventeenth century: and it construed this revolution, which it thought of as beginning with a revolution in Mathematics and Astronomy, and broadening into one that embraced the whole of "science", as in essence the progressive application of human reason.

Leading Philosophes |

|

| Jean le Rond D'Alembert | 1717-1783 |

| Denis Diderot | 1713-1784 |

| Paul-Henri Thiry, Baron d'Holbach | 1723-1789 |

| Charles-Louis de Secondat, Baron de Montesquieu | 1689-1755 |

| Jean-Jacques Rousseau | 1712-1778 |

| Voltaire | 1694-1778 |

This was their self-placement. But of course a period is not in a position to see its own foundations clearly enough to be relied upon in judgements of this kind.

A note on the growth of Eurpean trade with the rest of the world which is an important part of the background to thought about nature is here. And there is also a note on land improvement.

We have already noted some of the leading features of the scientific world view as a consensus began to get established at the end of the 17th Century. Here I set out those points with one or two we omitted earlier:

|

Here is Simon Scharma's History of Britain site |

First, established science was seen as assuming that the universe and its basic elements were inert. The distinction between inert (or passive) and active was clearly recognized in medieval thought. A passive body was one which was simply washed about in the tide of events. It might move because it was pushed, or perhaps because it was pulled, but insofar as it was indeed 'passive' it 'took no initiative' of its own, as it were. An active thing, on the other hand, was one which was capable of launching into movement spontaneously. Active things were thought of as possessing a 'power' inside them which was capable of initiating change. Not everybody in the Enlightenment period thought there were such things!

Thomas Hobbes for example held that everything that happened in the Universe could be explained in terms of masses of small particles which were perfectly passive: they moved about, but only because they kept being bumped into by the others!

This is 'atomism' in a particularly clear form: the universe is made up entirely of indivisibly small particles - jostling about, but perfectly inert - and everything about the universe, all the changes that go on as well as all the appearances it presents to us - of colours, smells, sounds and so on - are to be explained in terms of these minute blobs and their senseless jiggling.

There were Enlightenment thinkers who were 'atomists' but who believed the atoms were active (Leibniz, at one point in his career at any rate, was one of these). Nevertheless, the passive conception predominated and it was this that entered into later conceptions of how the universe was thought of by the Enlightenment. It was thought of as made up of minute hard passive particles..

The predominant form of Enlightenment atomism, gives us one clear example of what it was to think of nature as in itself 'inert'.

There is another great picture rooted in the Enlightenment but meaningful to us still today, and that is the metaphor of the universe as a great machine. This too invites the idea that nature is passive. Clockwork is a contrivance of parts, each of which is brought into movement by something else. None of the parts 'takes any initiative' of its own.

Part of the Enlightenment Project was to bring to bear the scientific mindset upon the human being itself, and when this was done generally speaking the passive conception of nature was taken. One influential approach was to think of 'ideas' as passive mental 'atoms'. Sensations dropped through the letterbox of the senses, then linked up in various ways and through various mechanisms. The object of the science of the human understanding was to work out the principles which governed the way in which such data of sense combined and otherwise related to each other - just as it was the object of the science of the natural world to establish the principles according to which atoms interacted to produce the observed phenomena of physics.

A third aspect of the Romantic conception of the 'Enlightenment' mindset was this. A part of atomism was - and still is - the idea that much of the ordinary experience we have as human beings is somehow a product of the interaction of atoms which in themselves have only a small number of simple properties. Atomism proposes to explain our experience of colour for example by reference to the movement of atoms which themselves are not coloured at all. Sound is put forward as some sort of movement of atoms. Smell similarly. Different atomists give different lists of the properties atoms are supposed to possess - and sometimes the same atomist gives different lists on different occasions! But the general thrust is to reduce. The world of human experience turns out, according to atomism, to be much more varied and rich than the reality underlying it all, which is for most atomists, a colourless, silent, odourless, tasteless skitter of tiny specks.

|

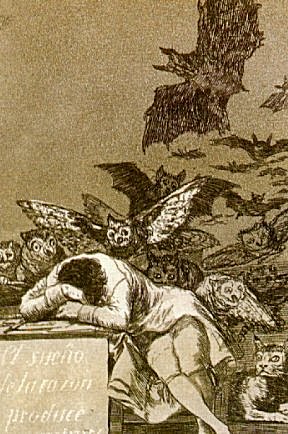

| Goya, The Sleep of Reason Generates Monsters |

The Enlightenment is often known as the Age of Reason. One justification for this epithet was that it had turned its back on the authority of the Church and the Bible and sought to base knowledge instead on whatever could be discovered and verified by human beings on their own. 'The motto of the Enlightenment,' Kant tells us, is this: S'apere aude! Have courage to use your own understanding.' (Kant, An Answer to the Question: "What is Enlightenment?", 1784.)

In this context 'reason' stood for the power of unaided human thought.

But 'reason' is sometimes used to make a different contrast, not between finding out ourselves and taking things on authority from something or somebody else, but between knowledge acquired by thought on its own (if indeed there is any) and knowledge acquired through experience. Emphasis on reason in this sense is to be found in the Enlightenment too, for example in the key role that had been ascribed, particularly in early phases of the scientific revolution, to mathematics. Some of the pioneers had certainly seen in mathematics the one and only key to understanding, so that science for them amounted to the progressive application of this form of reasoning to all the possible fields of human knowledge.

Reason for the 18th Century thinkers embraced a great deal that was later distinguished from it. It corresponds most closely to the later comprehensive notion of thinking itself.

This is brought by this typical passage by the philosophe D'Alambert, (as it was evident also in the account of 'reason' given by Locke which we looked at earlier).

"Physical beings act on the senses. The impressions of these beings stimulate perceptions of them in the understanding. The understanding is concerned with its perceptions in only three ways, according to its three principal faculties: memory, reason and imagination. Either the understanding makes a pure and simple enumeration of its perceptions through memory, or it examines them, compares them, and digests them, by means of reason; or it chooses to imitate them, and reproduce them through imagination. Whence results the apparently well-founded general distribution of human knowledge into history, which is related to memory; into philosophy, which emanates from reason; and into poetry, which arises from imagination."

D'Alembert, Preliminary Discourse to Diderot's Encyclopaedia.

It would be quite misleading however to think of the 18th Century as extolling reason at the expense of experience. Its ideology is actually that experience, reasoned about, is the chief or only source of human knowledge.

The Enlightenment also made 'reason' mark an inferior placement of feeling. For example, classifications appealed to properties which could be observed through the senses: especially shape, size, how the parts were arranged in space, how many there were. Plants were never classified on the basis, for example, of how they made you feel - of the pleasure they prompted as you encountered them, or of the emotions they conjured up within you as they were eaten. And that whole dimension of the role of plants in our lives was discounted as not relevant to the project of science.

Human emotion did enter into Enlightenment discourse in one form however. It was thought to play a part, and a key part, in the determination of human action. David Hume is famous for his view that ... and many other thinkers of the period thought of the relationship between human emotion and human reason and action in the same way. It is when we ask about what determined the emotions in their turn that we see what the Romantics were objecting to. For Hume and other Enlightenment thinkers saw emotion in quasi mechanical terms. We were born with a repertoire of emotional responses, and particular responses were triggered by eventualities impinging upon us. Once triggered a response then motivated action.

This treats the emotions as cogs in a machine. They play a part in the machinery which produces action. But they don't originate it.

[This conception of the role of feeling in human life is reflected in the old concept of the 'passions', which was displaced by the concept of 'emotion' in the late 18th Century (Roger Smith, Human Sciences, p. 60). They were interpreted as the result of influences impinging from without.]

What do you think?How do we think of feelings and their role in life today? How seriously do we respect the view that we should be guided by our feelings (eg when piloting a war plane)? |

In thinking of the human being as a 'subject for science' Enlightenment thinkers seemed to be committed to the idea that what needed to be understood about human behaviour was its causation. I have said that a leading idea was to treat thought in the same way - what was to be understood was what brought such and such a thought about, and to regard thoughts, including feelings, as playing a part in the machinery which brought about behaviour. But this way of thinking of the human being brought with it the suggestion - the implication perhaps - that human beings were at the mercy of the causal forces. In this way human freedom seemed to be under threat. If what you did was a result of the sort of causes which it was the business of science to identify, this seemed to take responsibility for your actions out of your hands. It wasn't just feelings that seemed like cogs in the clockwork from this point of view - it seemed implied that the human being as a whole was a component in some gigantic machine.

The characteristic of a machine is that each part of it comes into play when caused to do so by some other part acting upon it. Without a prompt, a part remains motionless. So in a machine, nothing happens without a cause. This nostrum, when applied to the universe as a whole, is the thesis of determinism. Determinism's thesis that 'every event has a cause' means that the occurrence of any event can be tied to a change in the circumstances that obtained at the time of its occurrence: in Leibniz' words, "Everything remains in the state in which it is if there is nothing to change it..." (Leibniz, Letter to Foucher, in Leibniz, Philosophical Writings trans. Morris, London, 1934, Everyman p. 48)

Determinism stands against the idea that some things that happen as it were spontaneously. Their occurrence is not fixed by prior conditions. And it has seemed to some that human freedom depends on there being some of these 'spontaneous' events - namely human 'acts of will'. Human acts of will, on this view, aren't determined by what has gone before. They are 'free'. And only if we think of them as free can we think of human action as anything other than bits of the universal machine turning.

The power to initiate change, exercised by human beings, on this view, when they act freely, means that sometimes a change happens while the circumstances in which it occurs remain unchanged. It is clearly a peculiar power: it is a power to bring something about, but one which is thought of as somehow not belonging to the circumstances within which the event in question occurs.

The determinism of the Enlightenment was expressed in its commitment to the idea that the universe was 'governed' by 'laws'.

|

Thomas L. Hankins, Science & the Enlightenment, Ch 1. A stimulating concise overview of the Enlightenment is offered by Robert C. Solomon in the prolegomenon to his Continental Philosophy since 1750, Oxford, 1988, OUP, pp.. 8-16, then Part 1 Section 2. A classic study of the Enlightenment: Carl Becker, The Heavenly City of the 18th Century Philosophers, New Haven & London, 1st Ed 1932, Yale University Press edition. |

As we discussed in Block 2, the Enlightenment belief was that the physical matter of which the universe was made up behaved in ways that were in principle law-governed.

What do you think?Are we still living in the Enlightenment? Or has the Postmodern era begun? |

Credits

Goya, The Sleep of Reason Generates Monsters, Courtesy UNIVERSITE BORDEAUX

I

Revised 06:06:04

IEPPP 406 Part 3 Home Page

IEPPP 406 Home Page

Reason, Nature and the Human Being in the West

Part of a module of the MA

in Values and the Environment Lancaster University

Send Mail to the Philosophy

Department