Fourth Encounter: In the Heart of the Conch: Libraries

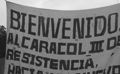

Find each other? Where? Let’s start looking in a library, one that is situated in the centric heart of a caracol, a conch: in La Garrucha. La Garrucha is one of five administrative centres on the land that the Zapatistas have reclaimed since 1994, and that now makes up Zapatista territory. The administrative centres are called caracoles because the Zapatista Good Government Councils meet here and they practice democracy as a journey to the heart, to the centre. If the journey is long, winding, or difficult, they won’t give in and they won’t give up: they’ll walk that path. They govern according to the principles ‘to rule by obeying’ and ‘everything for everyone, nothing for us.’

We find the library in La Garrucha because someone we met on the journey shows us where it is, and takes us. The library is a small room with books piled on shelves that are pushed to the back wall. And here we find Rogelio Ruedas Segura, who will tell us more about it. More precisely: about the library that used to be here, and about a library that has been burnt.

My name is Rogelio Ruedas Segura, and since 1995 I was involved in the construction of the library in the community Francisco Gómez. This is a very interesting story. When the Zapatistas rise up in 1994, and when a war takes place until 12th of January 1994, civil society sees on TV the massacre that the president Carlos Salinas de Gortari perpetrates against the indigenous people. Civil society exercises political pressure to stop the war. The army and the EZLN are obligated to dialogue. Peace negotiations are initiated. The command of the EZLN is located in the community Guadalupe Tepeyac, and the Subcomandante Insurgente Marcos, the military commander of the EZLN decides to rename this community Aguascalientes Guadalupe Tepeyac. The name is a reminder of the town Aguascalientes, where Emiliano Zapata and Pancho Villa signed peace treaties with each other and with a delegation of Venestiano Carranza, to end the Mexican revolution. Carranza betrays the peace treaty and orders the assassination of Zapata and Villa.

After the Uprising, many groups from Mexican civil society and the Zapatistas start finding each other. People form collectives and brigadas go out to work with Zapatista communities. Rogelio was one of them:

I worked with a collective called ‘Caravana Mexicana Para Todos Todo’, ‘Mexican caravana Everything for Everyone‘, and we went to Zapatista territory. We had been setting up a library in the community Guadalupe Tepeyac. We had started a campaign among intellectuals and artists, and asked for donations of books. We got together 13,000 books within one or two months. An important collection of very interesting books. And we set up the library.

The Zapatistas invite national and international civil society to meetings: one of the first is the Democratic National Convention. They build an ‘Aguascalientes’ to receive their visitors and to hold the meeting. The building has the shape of a sea shell, or a conch: The Sea Shell of the End and the Beginning

In February 1996 the government of the newly elected Mexican president Ernesto Zedillo betrays the peace negotiations with the EZLN, and sends in the army to arrest the Subcomandante Marcos. The army enters the town of Guadalupe Tepeyac, and they destroy it. The Subcomandante Marcos said at the time that the government had betrayed its own words, and that it had destroyed a space that symbolised peace in Mexico: the entire Aguascalientes, including the library. They burnt all of it. The entire construction had been made of wood, the library, all the buildings. The army burnt it all.

In February 1996 the government of the newly elected Mexican president Ernesto Zedillo betrays the peace negotiations with the EZLN, and sends in the army to arrest the Subcomandante Marcos. The army enters the town of Guadalupe Tepeyac, and they destroy it. The Subcomandante Marcos said at the time that the government had betrayed its own words, and that it had destroyed a space that symbolised peace in Mexico: the entire Aguascalientes, including the library. They burnt all of it. The entire construction had been made of wood, the library, all the buildings. The army burnt it all.

Did you read the ‘Story of the Questions’ in the previous post? The letter that frames the story was written from Guadalupe Tepeyac. The children mentioned in the letter – Heriberto, Eva, Toñita –are known as ‘the children of Guadalupe Tepeyac.’ Those who hold power in the Global North did not pay these events much mind. Ernesto Zedillo, after his presidential term ended, became a professor at Yale University. I’m sure they have a library there, too, though it may hold different types of books.

The Subcomandante Marcos said at the time that the Zapatistas would not respond with violence. If the army destroyed a space that symbolised peace, we would build many Aguascalientes, many spaces of peace. And we decided to build a library in each Aguascalientes, in each space of peace. We built this library in 1996, and it was an unusual and lively library until 2003. Here we gave workshops for the kids, and school was held in here. There were many materials. The library was full of life.

In 2003 there is a political change. The Aguascalientes are no longer called Aguascalientes, they are transformed into caracoles. It’s a change in the political and military administration. But the Zapatistas communities are surrounded by the army, and this leads to very specific and complex pressures. And the library had to be closed. There was no one who could look after it. It stayed closed for a while, then the community opened it again but used it in a different way. Now it’s sometimes a shop, sometimes people sleep here, whatever they need the space for. The library itself became less important. This is why the books haven’t been looked after, why they are dirty and damaged, why many books are missing. They are in disorder. The libraries in the other caracoles are in similar conditions. It’s because of the military pressure on the communities. It is difficult to maintain a library under these circumstances. The urgency is not to read, but to survive. There are many immediate needs, like keeping up the cornfields. Reading takes a backseat. For now.

Rogelio’s collective ceased to exist in 2003. A story of defeat? Only if you want to read it that way. Rogelio doesn’t: he points out that the Zapatista communities are engaging with the problems they are facing, and that many of those who were part of his collective continue to visit the Zapatistas communities and now, ten years later, still carry out different types of work in their support now.

A story of defeat? How about we finally start caring about the Mexican army burning spaces of peace on Zapatista territory? How about we finally start caring about the paramilitary attacks on Zapatista communities? How about we finally start caring about a situation that makes it difficult to read not because people don’t know how to read, but because danger doesn’t leave them the mindspace? How about we finally start turning our love for literature into a commitment to concrete, tangible, locatable peace?

***

brought together stories of resistance from many different cultural and political contexts. Those who donated the books wanted to share with the Zapatistas poetic words of resistance that mattered to them, and the Zapatistas accepted this gift and engaged with those words and stories.

Consider that reading takes time and effort which have to be taken away from other important tasks. Imagine you have the opportunity to share poetic words of resistance from your calendar and your geography. Imagine you’re part of building a space of peace. A space where people find each other.

Which book would you put inside that space of peace, so that others can find you? In which poem will we find the seed of your dignity? Which story takes us on a long-winded journey – as if we were travelling through a conch – to the centric heart of your resistance?