Dear Reader,

Forgive me for disappearing on you without previous warning. I’ll be truthful and make it worse: I’m not sorry, I won’t explain myself, I won’t apologise, and I won’t change my ways. Will you bear with me in spite of my disappearances? I’d like you to, but it’s up to you.

Anyway, I have something for you. A Zapatista community gave me a story for you. Yes, it’s a gift. As readers and ‘critics’ we are used to people asking for our attention and offering us stories or poems. Or we take pieces of writing that we find worthy of our time and attention. But this story comes to you in a different way. No-one is asking for your attention, your approval, or your opinion.

This is how I explained ‘you’ to them: a group of people who would like to learn about others, from different places, through their stories and poems. In this conversation, ‘to learn’ means something like this: you’re listening with an open heart. You’re willing to ask questions about your ways; maybe you’re even willing and able to change them. You will not provide recognition, because this means that you force their images and stories into your concepts. You will not exercise privilege; you will hear their story with humility, with an open heart, and without judgement.

Think of it as learning to receive.

The theorists of coloniality say that colonialism created the ‘condemned.’ They are those who have been deprived of their ability to give, because everything has been taken from them. Conversely, this means that those of us who are privileged within coloniality cannot receive in equality from an ‘Other.’ We can only ‘give’ – spell ‘impose’ – what we think other people need so that they can become more like us. And we get all squirmy when we’re told that there are people who should be the equivalent of the condemned and who refuse the sentence, who refuse to beg, who don’t take charity, who aren’t interested in our recognition, who don’t want to become like us. We get all squirmy and our words become all wriggly and we exercise different types of violence, because before those who refuse to accept condemnation we feel as privileged people without the ability to receive from an ‘Other’ in equality. In spite of everything we’ve done, we have never said we’re sorry; we have never apologized; we have never publicly and collectively committed to changing our ways.

The theorists of coloniality say that colonialism created the ‘condemned.’ They are those who have been deprived of their ability to give, because everything has been taken from them. Conversely, this means that those of us who are privileged within coloniality cannot receive in equality from an ‘Other.’ We can only ‘give’ – spell ‘impose’ – what we think other people need so that they can become more like us. And we get all squirmy when we’re told that there are people who should be the equivalent of the condemned and who refuse the sentence, who refuse to beg, who don’t take charity, who aren’t interested in our recognition, who don’t want to become like us. We get all squirmy and our words become all wriggly and we exercise different types of violence, because before those who refuse to accept condemnation we feel as privileged people without the ability to receive from an ‘Other’ in equality. In spite of everything we’ve done, we have never said we’re sorry; we have never apologized; we have never publicly and collectively committed to changing our ways.

With this story they’re giving us another chance.

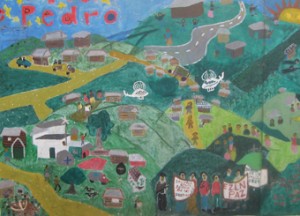

The story comes without the cultural translator Subcomandante Marcos, and directly from a village that is also a space of peace. The people who gave you this story are from three different indigenous cultures, and they built their village after that terrible year of 1996 when paramilitary groups waged a war in the Highlands of Chiapas against Zapatista communities and all other indigenous communities that positioned themselves against the hegemonic neoliberal paradigm; for example the pacifist community called Las Abejas, the Honeybees, who became victims of the terrible massacre of Acteal. Many people were displaced, among them about 2000 Zapatistas. Zapatista communities from other areas received the displaced Zapatistas on recuperated land, and built new homes. This village is one of them. The mural on the photo tells their story in image.

They also write and sing their own stories, but those aren’t meant for people who don’t share their commitment. Every night, a group of them gets together to write and practice corridos. Those are ballads, which are performed with music. They write them down in a thick note pad. They also built their own library. It contains – among other books, posters, poems, and printed and written material of all kinds – the educators’ companion books for the history classes in their school. Those books tell the story of their past — and of their past in their present — as a story of resistance to conquest, colonisation, and capitalism; as a story of knowledge of Self, respect for the Other, delight in equal difference, companionship with their natural environment, and of the unity of wisdom and knowledge. All of the materials – stacks and stacks of them – are written and illustrated by hand.

Here goes the story they picked for you. You can listen to it told, in Spanish, if you click on the audio.

When it was told we were sitting in front of the mural; adults and children from the community, from several cities in Mexico, from several countries. After this story was told, the same person told another one. Then another person told one. And then another person told a story. And so on.

***

This is the story of the Rabbit and the Tiger. One day the Rabbit and the Tiger ran into each other. The Tiger said that he wanted to go to war with the Rabbit. The Tiger asked the Rabbit whether he wanted to go to war with him, and the Rabbit agreed. Each of them went away and they got together their warriors and they set up their warfare. The Tiger first got together the deer, the tepizcuincle, the wild boar, and the animal we call tejón. The rabbit sat down and had a think about who he would get together to go to war. And so he united the wasps, all the different types of wasps that we have here. Those who can get into the ears, the eyes, the nose. Those are the ones the little Rabbit brought together.

And now that they had their warriors together they proposed that there should be war. So on the agreed day they came to meet each other, and the Tiger and the Rabbit faced each other. The little Rabbit sent all the wasps into the noses and eyes of the Tiger and the tejón and all the Tigers’ warriors, and they stung! The Tiger and his warriors ran away, they couldn’t go to war any more. And so the little Rabbit won, because he sent all the wasps up the noses and ears. The little Rabbit was very little, but he still won. Because he was smarter.

The Tiger ran back home. On the next day he wanted to pursue the Rabbit, who had also gone away. The Rabbit had arrived at the banks of a river. That’s where the Tiger found him. By the bank of the river was a tree, half on the bank and half in the water. And when the Tiger arrived he saw the face of the rabbit in the water. But the rabbit wasn’t in the water, he was outside. The Tiger thought ‘How do I get the Rabbit out of the water?’ And he thought: ‘I’ll drink all the water because this way I can get hold of the Rabbit.’ He started to drink all the water, and he collapsed, it was too much water. The Tiger died.

The Tiger ran back home. On the next day he wanted to pursue the Rabbit, who had also gone away. The Rabbit had arrived at the banks of a river. That’s where the Tiger found him. By the bank of the river was a tree, half on the bank and half in the water. And when the Tiger arrived he saw the face of the rabbit in the water. But the rabbit wasn’t in the water, he was outside. The Tiger thought ‘How do I get the Rabbit out of the water?’ And he thought: ‘I’ll drink all the water because this way I can get hold of the Rabbit.’ He started to drink all the water, and he collapsed, it was too much water. The Tiger died.

The Rabbit was pleased because he had won over the Tiger. He started to take the skin off the Tiger, because the Tiger’s fur is very beautiful. The little Rabbit used it for his drum, and he wrapped his guitar with it. His guitar looked very pretty. The next day he met the Fox. And the Fox said ‘Your guitar is very pretty, let me play it for a little while.’ The little Rabbit was suspicious because he thought that the Fox might not return the guitar. But he lent the guitar to the Fox, and the Fox started to play. The Fox gave it back, and then they went home.

The next day they ran into each other again, and the Fox said: ‘Let me borrow your guitar again, I want to play.’ And now the rabbit trusted him because he’d already returned the guitar once. The Fox started to play – and there he ran away with the guitar. And the Rabbit was left without a guitar. The Rabbit started to think about how he might get the guitar back.

The next day he saw the Fox, sitting in the sun and playing the guitar. So he thought, ‘How will I get my guitar back?’ And he united all the ants, red ones and black ones. And when they saw the Fox sitting there, they started to sting him all over his body. The Fox starts to scratch himself, and he dropped the guitar. And the Rabbit got hold of his guitar and was very happy.

That’s it. The End.

***

Will you make the story your point of departure? It can be the centre of your conch: from here, you could start to walk by asking questions. That is: if you take this decision. If you do, you could start with this question: Do we have a story we could share with them, in equality?

http://olharesnomadas.blog.com/