Exploring John Ruskin’s relationship with and appreciation of printmaking as an art form.

When John Ruskin first encountered the work of J.M.W. Turner, it was through the medium of engraved prints in a book of poems given to him in 1832 for his thirteenth birthday.

The influence of that book, Samuel Rogers' Italy, lasted a lifetime. Fifty-seven years later, struggling against mental illness to complete what would be the final chapter of his autobiography, one of the things Ruskin chose to write about was the importance of a select group of Turner's engraved prints. In Praeterita, Ruskin writes "I had no sooner cast eyes on the Rogers vignettes than I took them for my only masters, and set myself to imitate them as far as I possibly could".

Illustration from Samuel Rogers' 'Italy': Lake of Como, engraved by E. Goodall after Turner

Ruskin's engagement with the art of printmaking was not a random pursuit, but a major occupation. For The Seven Lamps of Architecture, The Stones of Venice and Modern Painters alone, he produced over 150 etched, engraved and lithographed plates and more than 200 engravings on wood. Some of these he produced himself, and others were made in collaboration with professional engravers, under Ruskin's careful supervision. Printmaking became far more to Ruskin than the merely practical matter of illustrating his books. He even elevated its importance above that of photography: “a square inch of man's engraving is worth all the photographs that ever were dipped in acid” (The Cestus of Aglaia). It was an art form which he deemed to be of high symbolic value, as it was dominated by the image of the engraver’s ‘pen of iron’, recording the noblest truths permanently into plates of steel. Ruskin saw the heavy responsibility shouldered by the printmaker: the technical difficulty of engraving, the many weeks of labour involved, the permanence of the result and the potential for printing hundreds and thousands of images.

Engravings after Ruskin from 'Friendship's Offering': Glacier des Boisand The Coast of Genoa, 1844

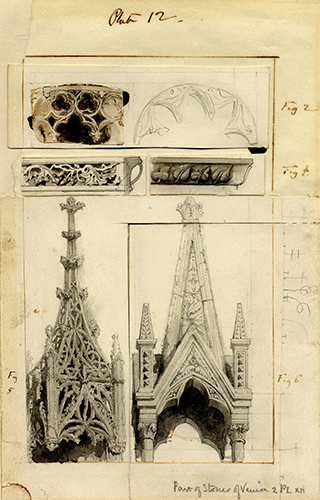

This exhibition began with a selection of original prints which provided a background to Ruskin's engagement with the medium of printmaking. It then offered the opportunity to explore a wide range of aspects of his own printmaking activities. By looking at progress proofs (none of which had been exhibited before), visitors to the Museum were able to view Ruskin's methods of work: developing a print and guiding the engraver towards the final image. They could also encounter the rich complexity of Ruskin’s ideas about engraving and its symbolic links to fundamental aspects of life, like the value of honest hard work. Works by Ruskin shown in this exhibition included an engraved print on the title page of his Collected Works, which was a symbol of his permanent love for Rose La Touche, as well as engravings of his own drawings of fine Gothic architecture which he made in an effort to preserve a permanent record of its beauty before it became more affected by decay and industrialisation.

John Ruskin: Linear and Surface Gothic (ink wash drawing) and Linear and Surface Gothic, engraved by R.P. Cuff for 'The Stones of Venice' (Vol. 2)

Other prints on display in this exhibition included Blake’s Newton, Millais’ Summer Indolence and Hunt’s Desolation of Egypt.

newweb.jpg)

John Everett Millais: Summer Indolence, 1861 (from 'Passages from Modern English Poets: illustrated by the Junior Etching Club')

The above description for this exhibition is an edited version of text written by Alan Davis: Visiting Fellow, The Ruskin Programme.