The mouth of the Hexi corridor in Gansu, where the Gobi meets the Taklamakan. A herd of camel flee from the oncoming train. Only the telegraph wires and the distant greenery on the edge of the Qilian Mountain Range reveal the presence of mankind.

The Early History of The Region

On the eastern and western sides of the continent, the civilisations of China and the West developed. The western end of the trade route appears to have developed earlier than the eastern end, principally because of the development of the the empires in the west, and the easier terrain of Persia and Syria. The Iranian empire of Persia was in control of a large area of the Middle East, extending as far as the Indian Kingdoms to the east. Trade between these two neighbours was already starting to influence the cultures of these regions.This region was taken over by Alexander the Great of Macedon, who finally conquered the Iranian empire, and colonised the area in about 330 B.C., superimposing the culture of the Greeks. Although he only ruled the area until 325 B.C., the effect of the Greek invasion was quite considerable. The Greek language was brought to the area, and Greek mythology was introduced. The aesthetics of Greek sculpture were merged with the ideas developed from the Indian kingdoms, and a separate local school of art emerged. By the third century B.C., the area had already become a crossroads of Asia, where Persian, Indian and Greek ideas met. It is believed that the residents of the Hunza valley in the Karakorum are the direct descendants of the army of Alexander; this valley is now followed by the Karakorum Highway, on its way from Pakistan over to Kashgar, and indicates how close to the Taklamakan Alexander may have got.

This `crossroads' region, covering the area to the south of the Hindu Kush and Karakorum ranges, now Pakistan and Afghanistan, was overrun by a number of different peoples. After the Greeks, the tribes from Palmyra, in Syria, and then Parthia, to the east of the Mediterranean, took over the region. These peoples were less sophisticated than the Greeks, and adopted the Greek language and coin system in this region, introducing their own influences in the fields of sculpture and art.

Close on the heels of the Parthians came the Yuezhi people from the Northern borders of the Taklamakan. They had been driven from their traditional homeland by the Xiongnu tribe (who later became the Huns and transferred their attentions towards Europe), and settled in Northern India. Their descendants became the Kushan people, and in the first century A.D. they moved into this crossroads area, bringing their adopted Buddhist religion with them. Like the other tribes before them, they adopted much of the Greek system that existed in the region. The product of this marriage of cultures was the Gandhara culture, based in what is now the Peshawar region of northwest Pakistan. This fused Greek and Buddhist art into a unique form, many of the sculptures of Buddhist deities bearing strong resemblances to the Greek mythological figure Heracles. The Kushan people were the first to show Buddha in human form, as before this time artists had preferred symbols such as the footprint, stupa or tree of enlightenment, either out of a sense of sacrilege or simply to avoid persecution.

The eastern end of the route developed rather more slowly. In China, the Warring States period was brought to an end by the Qin state, which unified China to form the Qin Dynasty, under Qin Shi Huangdi. The harsh reforms introduced to bring the individual states together seem brutal now, but the unification of the language, and standardisation of the system, had long lasting effects. The capital was set up in Changan, which rapidly developed into a large city, now Xian.

The Xiongnu tribe had been periodically invading the northern borders during the Warring States period with increasing frequency. The northern-most states had been trying to counteract this by building defensive walls to hinder the invaders, and warn of their approach. Under the Qin Dynasty, in an attempt to subdue the Xiongnu, a campaign to join these sections of wall was initiated, and the `Great Wall' was born. When the Qin collapsed in 206 B.C., after only 15 years, the unity of China was preserved by the Western Han Dynasty, which continued to construct the Wall.

During one of their campaigns against the Xiongnu, in the reign of Emperor Wudi, the Han learnt from some of their prisoners that the Yuezhi had been driven further to the west. It was decided to try to link up with these peoples in order to form an alliance against the Xiongnu. The first intelligence operation in this direction was in 138 B.C. under the leadership of Zhang Qian, brought back much of interest to the court, with information about hitherto unknown states to the west, and about a new, larger breed of horse that could be used to equip the Han cavalry. The trip was certainly eventful, as the Xiongnu captured them, and kept them hostage for ten years; after escaping and continuing the journey, Zhang Qian eventually found the Yuezhi in Northern India. Unfortunately for the Han, they had lost any interest in forming an alliance against the Xiongnu. On the return journey, Zhang Qian and his delegation were again captured, and it was not until 125 B.C. that they arrived back in Changan. The emperor was much interested by what they found, however, and more expeditions were sent out towards the West over the following years. After a few failures, a large expedition managed to obtain some of the so-called `heavenly horses', which helped transform the Han cavalry. These horses have been immortalised in the art of the period, one of the best examples being the small bronze `flying horse' found at Wuwei in the Gansu Corridor, now used as the emblem of the China International Travel Service. Spurred on by their discoveries, the Han missions pushed further westwards, and may have got as far as Persia. They brought back many objects from these regions, in particular some of the religious artwork from the Gandharan culture, and other objects of beauty for the emperor. By this process, the route to the west was opened up. Zhang Qian is still seen by many to be the father of the Silk Road.

In the west, the Greek empire was taken over by the Roman empire. Even at this stage, before the time of Zhang Qian, small quantities of Chinese goods, including silk, were reaching the west. This is likely to have arrived with individual traders, who may have started to make the journey in search of new markets despite the danger or the political situation of the time.

The Nature of the Route

The description of this route to the west as the `Silk Road' is somewhat misleading. Firstly, no single route was taken; crossing Central Asia several different branches developed, passing through different oasis settlements. The routes all started from the capital in Changan, headed up the Gansu corridor, and reached Dunhuang on the edge of the Taklamakan. The northern route then passed through Yumen Guan (Jade Gate Pass) and crossed the neck of the Gobi desert to Hami (Kumul), before following the Tianshan mountains round the northern fringes of the Taklamakan. It passed through the major oases of Turfan and Kuqa before arriving at Kashgar, at the foot of the Pamirs. The southern route branched off at Dunhuang, passing through the Yang Guan and skirting the southern edges of the desert, via Miran, Hetian (Khotan) and Shache (Yarkand), finally turning north again to meet the other route at Kashgar. Numerous other routes were also used to a lesser extent; one branched off from the southern route and headed through the Eastern end of the Taklamakan to the city of Loulan, before joining the Northern route at Korla. Kashgar became the new crossroads of Asia; from here the routes again divided, heading across the Pamirs to Samarkand and to the south of the Caspian Sea, or to the South, over the Karakorum into India; a further route split from the northern route after Kuqa and headed across the Tianshan range to eventually reach the shores of the Caspian Sea, via Tashkent.Secondly, the Silk Road was not a trade route that existed solely for the purpose of trading in silk; many other commodities were also traded, from gold and ivory to exotic animals and plants. Of all the precious goods crossing this area, silk was perhaps the most remarkable for the people of the West. It is often thought that the Romans had first encountered silk in one of their campaigns against the Parthians in 53 B.C, and realised that it could not have been produced by this relatively unsophisticated people. They reputedly learnt from Parthian prisoners that it came from a mysterious tribe in the east, who they came to refer to as the silk people, `Seres'. In practice, it is likely that silk and other goods were beginning to filter into Europe before this time, though only in very small quantities. The Romans obtained samples of this new material, and it quickly became very popular in Rome, for its soft texture and attractiveness. The Parthians quickly realised that there was money to be made from trading the material, and sent trade missions towards the east. The Romans also sent their own agents out to explore the route, and to try to obtain silk at a lower price than that set by the Parthians. For this reason, the trade route to the East was seen by the Romans as a route for silk rather than the other goods that were traded. The name `Silk Road' itself does not originate from the Romans, however, but is a nineteenth century term, coined by the German scholar, von Richthofen.

In addition to silk, the route carried many other precious commodities. Caravans heading towards China carried gold and other precious metals, ivory, precious stones, and glass, which was not manufactured in China until the fifth century. In the opposite direction furs, ceramics, jade, bronze objects, lacquer and iron were carried. Many of these goods were bartered for others along the way, and objects often changed hands several times. There are no records of Roman traders being seen in Changan, nor Chinese merchants in Rome, though their goods were appreciated in both places. This would obviously have been in the interests of the Parthians and other middlemen, who took as large a profit from the change of hands as they could.

The Development of the Route

The development of these Central Asian trade routes caused some problems for the Han rulers in China. Bandits soon learnt of the precious goods travelling up the Gansu Corridor and skirting the Taklamakan, and took advantage of the terrain to plunder these caravans. Caravans of goods needed their own defence forces, and this was an added cost for the merchants making the trip. The route took the caravans to the farthest extent of the Han Empire, and policing this route became a big problem. This was partially overcome by building forts and defensive walls along part of the route. Sections of `Great Wall' were built along the northern side of the Gansu Corridor, to try to prevent the Xiongnu from harming the trade; Tibetan bandits from the Qilian mountains to the south were also a problem. Sections of Han dynasty wall can still be seen as far as Yumen Guan, well beyond the recognised beginning of the Great Wall at Jiayuguan. However, these fortifications were not all as effective as intended, as the Chinese lost control of sections of the route at regular intervals.

After the Western Han dynasty, successive dynasties brought more states

under Chinese control. Settlements came and went, as they changed hands or lost

importance due to a change in the routes. The Chinese garrison town of Loulan,

for example, on the edge of the Lop Nor lake, was important in the third

century A.D., but was abandoned when the Chinese lost control of the route for

a period. Many settlements were buried during times of abandonment by the sands

of the Taklamakan, and could not be repopulated.

The settlements reflected the nature of the trade passing through the region.

Silk, on its way to the west, often got no further than this region of Central

Asia. The Astana tombs, where the nobles of Gaochang were buried, have turned

up examples of silk cloth from China, as well as objects from as far afield as

Persia and India. Much can be learned about the customs of the time from the

objects found in these graves, and from the art work of the time, which has

been excellently preserved on the tomb walls, due to the extremely dry

conditions. The bodies themselves have also been well preserved, and may allow

scientific studies to ascertain their origins.

The most significant commodity carried along this route was

not silk, but religion. Buddhism came to China from India this way, along the

northern branch of the route. The first influences came as the passes over the

Karakorum were first explored. The Eastern Han emperor Mingdi is thought to

have sent a representative to India to discover more about this strange faith,

and further missions returned bearing scriptures, and bringing with them India

priests. With this came influences from the Indian sub-continent, including

Buddhist art work, examples of which have been found in several early second

century tombs in present-day Sichuan province.

This was considerably influenced by the Himalayan Massif, an

effective barrier between China and India, and hence the Buddhism in China is

effectively derived from the Gandhara culture by the bend in the Indus river,

rather than directly from India. Buddhism reached the pastures of Tibet at a

rather later period, not developing fully until the seventh century. Along

the way it developed

under many different influences, before reaching central China. This is

displayed very cleared in the artwork, where many of the cave paintings show

people with clearly different ethnic backgrounds, rather than the expected

Central and East Asian peoples.

The greatest flux of Buddhism into China occurred during the Northern Wei

dynasty, in the fourth and fifth centuries A.D.

This was at a time when China was divided into several different kingdoms,

and the Northern Wei dynasty had its capital in Datong in present day Shanxi

province. The rulers encouraged the development of Buddhism, and more missions

were sent towards India. The new religion spread slowly eastwards, through the

oases surrounding the Taklamakan, encouraged by an increasing number of

merchants, missionaries and pilgrims. Many of the local peoples, the Huihe

included, adopted Buddhism as their own religion. Faxian, a pilgrim from China,

records the religious life in the Kingdoms of Khotan and Kashgar in 399 A.D. in

great detail. He describes the large number of monasteries that had been

built, and a large Buddhist festival that was held while he was there.

Some devotees were sufficiently inspired by the new ideas that they headed off

in search of the source, towards Gandhara and India; others started to build

monasteries, grottoes and stupas. The development of the grotto is particularly

interesting; the edges of the Taklamakan hide some of the best examples in the

world. The hills surrounding the desert are mostly of sandstone, with any

streams or rivers carving cliffs that can be relatively easily dug into; there

was also no shortage of funds for the work, particularly from wealthy

merchants, anxious to invoke protection or give thanks for a safe desert

crossing. Gifts and donations of this kind were seen as an act of merit, which

might enable the donor to escape rebirth into this world. In many of the

murals, the donors themselves are depicted, often in pious attitude. This

explains why the Mogao grottoes contain some of the best examples of Buddhist

artwork; Dunhuang is the starting point for the most difficult section of the

Taklamakan crossing.

The grottoes were mostly started at about the same period, and coincided with

the beginning of the Northern Wei Dynasty. There are a large cluster in the

Kuqa region, the best examples being the Kyzil grottoes; similarly there are

clusters close to Gaochang, the largest being the Bezeklik grottoes.

Probably the best known ones are the Mogao grottoes

at Dunhuang, at the eastern end of the

Taklamakan. It is here that the greatest number, and some of the best examples,

are to be found. More is known about the origins of these, too, as large

quantities of ancient documents have been found. These are on a wide range of

subjects, and include a large number of Buddhist scriptures in Chinese,

Sanskrit, Tibetan, Uygur and other languages, some still unknown. There are

documents from the other faiths that developed in the area, and also some

official documents and letters that reveal a lot about the system of government

at the time.

For the archaeologist these grottoes are particularly valuable sources of

information about the Silk Road. Along with the images of Buddhas and

Boddhisatvas, there are scenes of the everyday life of the people at the time.

Scenes of celebration and dancing give an insight into local customs and

costume. The influences of the Silk Road traffic are therefore quite clear in

the mix of cultures that appears on these murals at different dates. In

particular, the development of Buddhism from the Indian/Gandharan style to a

more individual faith is evident on studying the murals from different eras in

any of the grotto clusters.

Those from the Gandharan school have more classical features, with

wavy hair and a sharper brow; they tend to be dressed in toga-like robes

rather than a loin cloth. Those of the Northern Wei have a more Indian

appearance, with narrower faces, stretched ear-lobes, and a more serene aura.

By the Tang dynasty, when Buddhism was well developed in China, many of the

statues and murals show much plumper, more rounded and amiable looking figures.

By the Tang dynasty, the Apsara (flying deity, similar to an angel in

Christianity) was a popular subject for the artists.

It is also interesting to trace the changes in styles along the length of

the route, from Kuqa in the west, via the Turfan area and Dunhuang, to the

Maijishan grottoes about 350 kilometres from Xian, and then as far into

China as Datong. The Northern Wei dynasty, that is perhaps the most responsible

for the spread of Buddhism in China, started the construction of the Yungang

grottoes in northern Shanxi province. When the capital of the Northern Wei was

transferred to Luoyang, the artists and masons started again from scratch,

building the Longmen grottoes. These two more `Chinese' grottoes emphasised

carving and statuary rather than the

delicate murals of the Taklamakan regions, and the figures are quite impressive

in their size; the largest figure at Yungang measures more than 17 metres in

height, second only in China to the great Leshan Buddha in Sichuan, which was

constructed in the early 8th Century. The figures are mostly depicted in the

`reassurance' pose, with right hand raised, as an apology to the adherents of

the Buddhist faith for the period of persecution that had occurred during the

early Northern Wei Dynasty before construction was started.

The Buddhist faith gave birth to a number of different sects in Central

Asia. Of these, the `Pure Land' and `Chan' (Zen) sects were particularly

strong, and were even taken beyond China; they are both still flourishing in

Japan.

Christianity also made an early appearance on the scene. The Nestorian sect

was outlawed in Europe by the Roman church in 432 A.D., and its followers were

driven eastwards. From

their foothold in Northern Iran, merchants brought the faith along the Silk

Road, and the first Nestorian church was consecrated at Changan in 638 A.D.

This sect took root on the Silk Road, and survived many later attempts to wipe

them out, lasting into the fourteenth century. Many Nestorian writings have

been found with other documents at Dunhuang and Turfan. Manichaeism, a third

century Persian religion, also influenced the area, and had become quite well

developed by the beginning of the Tang Dynasty.

During this period, in the seventh century, the Chinese traveller Xuan Zhuang

crossed the region on his way to obtain Buddhist scriptures from India.

He followed the northern branch round the Taklamakan on his outward journey,

and the southern route on his return; he carefully recorded the cultures and

styles of Buddhism along the way. On his return to the Tang capital at Changan,

he was permitted to build the `Great Goose Pagoda' in the southern half of the

city, to house the more than 600 scriptures that he had brought back from

India. He is still

seen by the Chinese as an important influence in the development of Buddhism in

China, and his travels were dramatised by in the popular classic `Tales of a

Journey to the West'.

The art and civilisation of the Silk Road achieved its highest point in the

Tang Dynasty. Changan, as the starting point of the route, as well as the

capital of the dynasty, developed into one of the largest and most cosmopolitan

cities of the time. By 742 A.D., the population had reached almost two million,

and the city itself covered almost the same area as present-day Xian,

considerably more than within the present walls of the city. The 754 A.D. census

showed that five thousand foreigners lived in the city; Turks, Iranians,

Indians and others from along the Road, as well as Japanese, Koreans and Malays

from the east. Many were missionaries, merchants or pilgrims, but every other

occupation was also represented. Rare plants, medicines, spices and other goods

from the west were to be found in the bazaars of the city. It is quite clear,

however, despite the exotic imports, that the Chinese regarded all foreigners

as barbarians; the gifts provided for the Emperors by foreign rulers were

simply considered as tribute from vassal states.

From the point of view of those in the far west, China was still an unknown

territory, and silk production was not understood. Since the days of Alexander

the Great, there had been some knowledge of India, but there was no real

knowledge of, or contact with,

the `Seres' until about the 7th century, when information started to filter

along the Road. It was at this time that the rise of Islam started to affect

Asia, and a curtain came down between the east and west. Trade relations soon

resumed, however, with the Muslims playing the part of middlemen. The sea route

to China was explored at this time, and the `Sea Silk Route' was opened,

eventually holding a more important place than the land route itself, as the

land route became less profitable.

But the final shake-up that occurred was to come from a different direction;

the hoards from the grasslands of Mongolia.

The partial unification of so many states under the Mongol Empire allowed a

significant interaction between cultures of different regions. The route of the

Silk Road became important as a path for communication between different parts

of the Empire, and trading was continued. Although less `civilised' than people

in the west, the Mongols were more open to ideas. Kubilai Khan, in particular,

is reported to have been quite sympathetic to most religions, and a large number

of people of different nationalities and creeds took part in the trade across

Asia, and settled in China. The most popular religion in China at the time was

Daoism, which at first the Mongols favoured. However, from the middle of the

thirteenth century onwards, buddhist influence increased, and the early lamaist

Buddhism from Tibet was particularly favoured. The two religions existed side by

side for a long period during the Yuan dynasty. This religious liberalism was

extended to all; Christianity first made headway in China in this period, with

the first Roman Catholic archbishopric set up in Beijing in 1307. The Nestorian

church was quite widespread in China; Jews and Muslims also populated several of

the major cities, though they do not seem to have made many converts.

It was at this time that Europeans first ventured towards the lands of the

`Seres'. The earliest were probably Fransiscan friars who are reported to have

visited the Mongolian city of Karakorum. The first Europeans to arrive at

Kubilai's court were Northern European traders, who arrived in 1261. However,

the most well known and best documented visitor was the Italian Marco Polo. As a

member of a merchant family from Venice, he was a good businessman and a keen

observer. Starting in 1271, at the age of only seventeen, his travels with his father

and uncle took him across Persia, and then along the southern branch of the Silk

Road, via Khotan, finally ending at the court of Kubilai Khan at Khanbalik, the

site of present-day Beijing, and the summer palace, better known as Xanadu. He

travelled quite extensively in China, before returning to Italy by ship, via

Sumatra and India to Hormuz and Constantinople.

He describes the way of life in the cities and small kingdoms through which

his party passed, with particular interest on the trade and marriage customs.

His classification of other races centre mainly on their religion, and he looks

at things with the eyes of one brought up under the auspices of the Catholic

Church; it is therefore not surprising that he has a great mistrust of the

Muslims, but he seems to have viewed the `Idolaters' (Buddhists and Hindus) with

more tolerance. He judges towns and countryside in terms of productivity; he

appears to be have been quick to observe available sources of food and water

along the way, and to size up the products and manufacture techniques of the

places they passed through. His description of exotic plants and beasts are

sufficiently accurate to be quite easily recognizable, and better than most of

the textbooks of the period. He seems to have shown little interest in the

history of the regions he was passing through, however, and his reports of

military campaigns are full of inaccuracies, though this might be due to other

additions or misinformation.

The `Travels' were not actually written by Marco Polo himself. After his

return to the West in 1295, he was captured as a prisoner of war in Genoa, when

serving in the Venetian forces. Whilst detained in prison for a year, he met

Rustichello of Pisa, a relatively well-known romance writer and a fellow

prisoner of war. Rustichello was obviously attracted to the possibilities of

writing a romantic tale of adventure about Polo's travels; it should be

remembered that the book was written for entertainment rather than as a historic

document. However, the collaboration between them, assuming that the story has

not been embroidered excessively by Rustichello, gives an interesting picture of

life along the Silk Road in the time of the Khans. Some of the tales are no

doubt due to the romance-writing instincts of Rustichello, and some of those due

to Polo are at best third-hand reports from people he met; however, much of the

material can be verified against Chinese and Persian records. As a whole, the

book captured public notice at the time, and added much to what was known of

Asian geography, customs and natural history.

Despite the presence of the Mongols, trade along the Silk Road never reached

the heights that it did in the Tang dynasty. The steady advance of Islam,

temporarily halted by the Mongols, continued until it formed a major force

across Central Asia, surrounding the Taklamakan like Buddhism had almost a

millennium earlier. The artwork of the region suffered under the encroach of

Islam. Whereas the Buddhist artists had concentrated on figures in painting and

sculpture, the human form was scorned in Islamic artwork; this difference led to

the destruction of much of the original artwork. Many of the grottoes have been

defaced in this way, particularly at the more accessible sites such as Bezeklik,

near Turfan, where most of the human faces in the remaining frescoes have been

scratched out.

The encroach of the deserts into the inhabited land made life on the edges of

the Taklamakan and Gobi Deserts particularly difficult. Any settlement abandoned

for a while was swallowed by the desert, and so resettlement became increasingly

difficult. These conditions were only suitable in times of peace, when effort

could be spent countering this advance, and maintaining water sources.

However, as trade with the West subsided, so did the traffic along the Road,

and all but the best watered oases survived. The grottoes and other religious

sites were long since neglected, now that the local peoples had espoused a new

religion, and the old towns and sites were buried deeper beneath the sands.

The study of the Road really took off after the expeditions of the Swede Sven

Hedin in 1895. He was an accomplished cartographer and linguist, and became one

of the most renowned explorers of the time. He crossed the Pamirs to Kashgar,

and then set out to explore the more desolate parts of the region. He even

succeeded in making a crossing of the centre of the Taklamakan, though he was

one of only three members of the party who made it across, the rest succumbing

to thirst after their water had run out. He was intrigued by local legends of

demons in the Taklamakan, guarding ancient cities full of treasure, and met

several natives who had chanced upon such places. In his later travels, he

discover several ruined cities on the south side of the desert, and his biggest

find, the city of Loulan, from which he removed a large number of ancient

manuscripts.

After Hedin, the archaeological race started. Sir Aurel Stein of Britain and

Albert von Le Coq of Germany were the principle players, though the Russians and

French, and then the Japanese, quickly followed suit. There followed a period of

frenzied digging around the edges of the Taklamakan, to discover as much as

possible about the old Buddhist culture that had existed long before. The

dryness of the climate, coupled with the exceedingly hot summers and cold

winters, made this particularly difficult. However the enthusiasm to discover

more of the treasures of the region, as well as the competition between the

individuals and nations involved, drove them to continue. Although they produced

reports of what they discovered, their excavation techniques were often far from

scientific, and they removed whatever they could from the sites in large packing

cases for transport to the museums at home. The manuscripts were probably the

most highly prized of the finds; tales of local people throwing these old

scrolls into rivers as rubbish tormented them. Removal of these from China

probably did help preserve them. However, the frescoes from the grottoes also

attracted their attention, and many of the best ones were cut into sections, and

carefully peeled off the wall with a layer of plaster; these were then packaged

very carefully for transport. To their credit, almost all these murals survived

the journey, albeit in pieces.

The crowning discovery was of a walled-up library within the Mogao grottoes

at Dunhuang. This contained a stack of thousands of manuscripts, Buddhist

paintings and silk temple banners. The manuscripts were in Chinese, Sanscrit,

Tibetan, Uighur and several other less widely known languages, and they covered

a wide range of subjects; everything from sections of the Lutras Sutra to

stories and ballads from the Tang dynasty and before. Among these is what is

believed to be the world's oldest printed book. This hoard had been discovered

by a Daoist monk at the beginning of the twentieth century, and he had appointed

himself as their protector. The Chinese authorities appear to have been aware of

the existence of the library, but were perhaps not fully aware of its

significance, and they had decided to leave the contents where they were, under

the protection of the monk. On hearing of this hoard, Stein came to see them; he

gradually persuaded the monk to part with a few of the best for a small donation

towards the rebuilding of the temple there. On successive visits, he removed

larger quantities; the French archaeologist Pelliot also got wind of this

discovery, and managed to obtain some. The frescoes at Dunhuang were also some

of the best on the whole route, and many of the most beautiful ones were removed

by the American professor Langdon Warner and his party.

The archaeological free-for-all came to a close after a change in the

political scene. On 25th May 1925 a student demonstration in the treaty port of

Shanghai was broken up by the British by opening fire on them, killing a number

of the rioters. This instantly created a wave of anti-foreign hostility

throughout China, and effectively brought the explorations of the Western

Archaeologists to an end. The Chinese authorities started to take a much harsher

view of the foreign intervention, and made the organisation of the trips much

more difficult; they started to insist that all finds should be turned over to

the relevant Chinese organs. This effectively brought an end to foreign

exploration of the region.

The treasures of the ancient Silk Road are now scattered around museums in

perhaps as many as a dozen countries. The biggest collections are in the British

Museum and in Delhi, due to Stein and in Berlin, due to von Le Coq. The

manuscripts attracted a lot of scholarly interest, and deciphering them is still

not quite complete. Most of them are now in the British Library, and available

for specialist study, but not on display. A large proportion of the Berlin

treasures were lost during the Second World War; twenty eight of the largest

frescoes, which had been attached to the walls of the old Ethnological Museum in

Berlin for the purposes of display to the public, were lost in an Allied Air

Force bombing raids between 1943 and 1945. A huge quantity of material brought

back to London by Stein has mostly remained where it was put; museums can never

afford the space to show more than just a few of the better relics, especially

not one with such a large worldwide historical coverage as the British Museum.

The Chinese have understandably taken a harsh view of the `treasure seeking'

of these early Western archaeologists. Much play is made on the removal of such

a large quantity of artwork from the country when it was in no state to formally

complain, and when the western regions, in particular, were under the control of

a succession of warlord leaders. There is a feeling that the West was taking

advantage of the relatively undeveloped China, and that many of the treasures

would have been much better preserved in China itself. This is not entirely

true; many of the grottoes were crumbling after more than a thousand years of

earthquakes, and substantial destruction was wrought by farmers improving the

irrigation systems. Between the visits of Stein and Warner to Dunhuang, a group

of White Russian soldiers fleeing into China had passed by, and defaced many of

the best remaining frescoes to such an extent that the irate Warner decided to

`salvage' as much as he could of the rest. The Chinese authorities at the time

seem to have known about the art treasures of places like Dunhuang, but don't

seem to have been prepared to protect them; the serious work of protection and

restoration was left until the formation of the People's Republic.

Their only consolation is that many of the scrolls which had been purchased

from native treasure-hunters at the western end of the Taklamakan at the

beginning of the century were later found to have been remarkably good

forgeries. Many were produced by an enterprising Muslim in Khotan, who had

sensed how much money would be involved in this trade. This severely embarrassed

a number of Western Orientalists, but the number of people misled attests to

their quality.

The fight of man against the desert, one of the biggest problems for the

early travellers, is finally gaining ground. There has been some progress in

controlling the progress of the shifting sands, which had previously meant

having to resite settlements. The construction of roads around the edges of the

Taklamakan has eased access, and the discovery of large oil reserves under the

desert has encouraged this development. The area is rapidly being

industrialised, and Urumchi, the present capital of Xinjiang, has become a

particularly unprepossessing Han Chinese industrial city.

The railway connecting Lanzhou to Urumchi has been extended to the border

with Kazakhstan, where on 12th September 1990 it was finally joined to the

former Soviet railway system, providing an important route to the new republics

and beyond. This Eurasian Continental Bridge, built to rival the Trans-Siberian

Railway, has been constructed from LianYunGang city in Jiangsu province (on the

East China coast) to Rotterdam; the first phase of this development has already

been completed, and the official opening of the railway was held on 1st December

1992. It is already promised to be at least 20% cheaper than the route by sea,

and at 11,000 kilometres is significantly shorter. From China the route passes

through Kazakhstan, Russia, Byelorussia and Poland, before reaching Germany and

the Netherlands. The double-tracking of the railway from Lanzhou to the border

of the C.I.S. has now been put high on the Chinese development priority list.

Archaeological excavations have been started by the Chinese where the

foreigners laid off; significant finds have been produced from such sites as the

Astana tombs, where the dead from the city of Gaochang were buried. Finds of

murals and clothing amongst the grave goods have increased knowledge of life

along the old Silk Road; the dryness of the climate has helped preserve the

bodies of the dead, as well as their garments.

There is still a lot to see around the Taklamakan, mostly in the form of

damaged grottoes and ruined cities. Whilst some people are drawn by the

archaeology, others are attracted by the minority peoples; there are thirteen

different races of people in the region, apart from the Han Chinese, from the

Tibetans and Mongolians in the east of the region, to the Tajik, Kazakhs and

Uzbeks in the west. Others are drawn to the mysterious cities such as Kashgar,

where the Sunday market maintains much of the old Silk Road spirit, with people

of many different nationalities selling everything from spice and wool to

livestock and silver knives. Many of the present-day travellers are Japanese,

visiting the places where their Buddhist religion passed on its way to Japan.

`China: A Guidebook to Xinjiang', Xinjiang Educational Press, Urumqi 1988.

Marco Polo, `The Travels', translated by R. Latham, Penguin, 1958.

Jin Bohong, `In the footsteps of Marco Polo', New World Press, Beijing 1989.

Xinjiang Educational Press, `China: A Guidebook to Xinjiang', Urumqi 1988.

Shaanxi Travel and Tourism Press, `The 40 Scenic Spots along the Silk Road',

Xian (1990****?)

Zhang Yehan (Ed.), `Si Lu You (Silk Road Tour)', Xinjiang People's Publishing

House, Urumchi, Vol.1 (1988), Vol.2 (1990).

Brian Hook (Ed.) `The Cambridge Encyclopedia of China', Cambridge U.P.,

(1991,2nd ed.)

Also the exhibition `The Crossroads of Asia', Fitzwilliam Museum (Cambridge), on until

mid-December 1992.

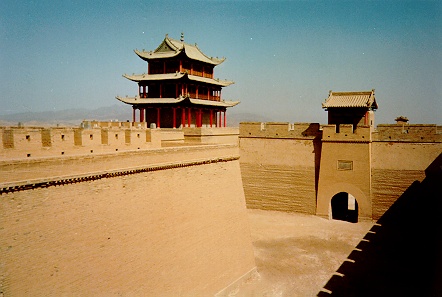

The fort at Jiayuguan marks the Western end of the Great Wall. The most recent fort was built as late as the Ming Dynasty; the massive fortifications are still clearly evident and only the wooden gate towers have been recently restored.

The Han dynasty set up the local government at Wulei, not far from Kuqa on

the northern border of the Taklamakan, in order to `protect' the states in

this area, which numbered about 50 at the time. At about the same period the

city of Gaochang was constructed in the Turfan basin. This developed into the

centre of the Huihe kingdom; these peoples later became the Uygur minority who

now make up a large proportion of the local population. Many settlements were

set up along the way, mostly in the oasis areas, and profited from the passing

trade. They also absorbed a lot of the local culture, and the cultures that

passed them by along the route. Very few merchants traversed the full length

of the road; most simply covered part of the journey, selling their wares a

little further from home, and then returning with the proceeds. Goods therefore

tended to moved slowly across Asia, changing hands many times. Local people no

doubt acted as guides for the caravans over the most dangerous sections of the

journey.

The Bezeklik Grottoes in the Flaming Mountains near Turfan hang precariously off a cliff above a steep gorge. However, the Buddhist carvings and murals within these caves were not sufficiently remote to escape both the onslaught of Islam and the intentions of foreign archaeologists and treasure seekers. Now there is a new threat: that of numerous coach loads of foreign and domestic tourists, keen to see what's left.

The grotto building was not confined to the Taklamakan; there is a large

cluster at Bamiyan in the Hindu Kush, in present-day Afghanistan. It is here

that the second largest sculpture of Buddha in the world can be found, at 55 metres high.

The Greatest Years

The height of the importance of the Silk Road was during

the Tang dynasty, with relative internal stability in China after the divisions

of the earlier dynasties since the Han. The individual states has mostly been

assimilated, and the threats from marauding peoples was rather less.

The muslim food street in Xian, the modern city that was once Changan, the Tang Dynasty capital. This street leads off the main westward thoroughfare only a stone's throw from the Drum Tower in the centre of the city which could justifiably lay claim to being the eastern end of the Silk Road; much of the muslim culture of Western China is still in evidence here.

After the Tang, however, the traffic along the road subsided, along with

the grotto building and art of the period. The Five Dynasties period did not

maintain the internal stability of the Tang dynasty, and again neighbouring

states started to plunder the caravans. China was partially unified again in

the Song dynasty, but the Silk Road was not as important as it had been in the

Tang.

The Mongols

Trade along the route was adversely affected by the strife which built up

between the Christian and Muslim worlds. The Crusades brought the Christian

world a little nearer to Central Asia, but the unified Muslim armies under

Saladin drove them back again. In the Fourth Crusade, the forces of Latin

Christianity scored a triumph over their Greek rivals, with the capture of

Constantinople (Istanbul). However, it was not the Christians who finally split

the Muslim world, but the Mongols from the east. Whilst Europe and Western Asia

were torn by religious differences, the Mongols had only the vaguest of

religious beliefs. Several of the tribes of Turkestan which had launched

offensives westwards towards Persia and Arabia, came to adopt Islam, and Islam

had spread far across Central Asia, but had not reached as far as the tribes

which wandered the vast grasslands of Mongolia. These nomadic peoples had

perfected the arts of archery and horsemanship. With an eye to expanding their

sphere of influence, they met in 1206 and elected a leader for their unified

forces; he took the title Great Khan. Under the leadership of Genghis Khan, they

rapidly proceeded to conquer a huge region of Asia. The former Han city of

Jiaohe, to the west of Turfan, was decimated by the Mongols as they passed

through on their way westwards. The Empire they carved out enveloped the whole

of Central Asia from China to Persia, and stretched as far west as the

Mediterranean. This Mongol empire was maintained after Genghis' death, with the

western section of the empire divided into three main lordships, falling to

various of his descendants as lesser Khans, and with the eastern part remaining

under the rule of the Great Khan, a title which was inherited from by Kublai

Khan. Kubilai completed the conquest of China, subduing the Song in the South of

the country, and established the Yuan dynasty.

The Decline of the Route

However, the Mongolian Empire was to be fairly short-lived. Splits between

the different khans had erupted as early as 1262. Although the East was

considerably more stable, especially under the rule of Kubilai, it also

succumbed to a resurgence of Chinese nationalism, and after several minor local

rebellions in the first few decades of the fourteenth century, principally in

the south of China, the Yuan dynasty was finally replaced by the Ming dynasty in

1368. With the disintegration of the Mongol empire, the revival of Islam and the

isolationist policies of the Ming dynasty, the barriers rose again on the land

route between East and West.

The Id Kah Mosque in Kashgar, spiritual centre of the town. Islam was one of the later imports along the Road, and now has a firm footing throughout Xinjiang.

The demise of the Silk Road also owes much to the development of the silk

route by sea. It was becoming rather easier and safer to transport goods by

water rather than overland. Ships had become stronger and more reliable , and

the route passed promising new markets in Southern Asia. The overland problems

of `tribal politics' between the different peoples along the route, and the

presence of middlemen, all taking their cut on the goods, prompted this move.

The sea route, however, suffered from the additional problems of bad weather and

pirates. In the early fifteenth century, the Chinese seafarer Zhang He commanded

seven major maritime expeditions to Southeast Asia and India, and as far as

Arabia and the east coast of Africa. Diplomatic relations were built up with

several countries along the route, and this increase the volume of trade Chinese

merchants brought to the area. In the end, the choice of route depended very

much upon the political climate of the time.

The ruins of Gaochang city, near Turfan. More than 1500 years ago this city was the centre of the Huihe kingdom; now the local Uygur people tend their flocks of sheep and goats in what were once the houses and streets of the provincial capital.

The attitude of the later Chinese dynasties was the final blow to the trade

route. The isolationist policies of the Ming dynasties did nothing to encourage

trade between China and the rapidly developing West. This attitude was

maintained throughout the Ming and Qing dynasties, and only started to change

after the Western powers began making inroads into China in the nineteenth

century. By the beginning of the Eighteenth Century, the Qing dynasty subdued

the Dzungar people, however, and annexed the whole Taklamakan region, forming

the basis of present-day Xinjiang province. This restored China to the state it

had been in in the Han dynasty, with full control of the western regions, but

also including the territories and Tibet and Mongolia.

Foreign Influence

Renewed interest in the Silk Road only emerged among western scholars towards

the end of the nineteenth century. This emerged after various countries started

to explore the region. The foreign involvement in this area was due mostly to

the interest of the powers of the time in expanding their territories. The

British, in particular, were interested in consolidating some of the land north

of their Indian territories. The first official trip for the Survey of India was

in 1863, and soon afterwards, the existence of ancient cities lost in the desert

was confirmed. A trade delegation was sent to Kashgar in 1890, and the British

were eventually to set up a consulate in 1908. They saw the presence of Russia

as a threat to the trade developing between Kashgar and India, and the power

struggle between these two empires in this region came to be referred to as the

`Great Game'. British agents (mostly Indians) crossed the Himalayas from Ladakh

and India to Kashgar, travelling as merchants, and gathering what information

they could, including surveying the geography of the route. At a similar time,

Russians were entering from the north; most were botanists, geologists or

cartographers, but they had no doubt been briefed to gather whatever

intelligence they could. The Russians were the first to chance on the ruined

cities at Turfan. The local treasure hunters were quick to make the best of

these travellers, both in this region and near Kashgar, and noting the interest

the foreigners showed towards the relics, sold them a few of the articles that

they had dug out of the ruins. In this way a few ancient articles and old

manuscripts started to appear in the West. When these reached the hands of

Orientalists in Europe, and the manuscripts were slowly deciphered, they caused

a large deal of interest, and more people were sent out to look out for them.

The Present Day

The Silk Road, after a long period of hibernation, has been increasing in

importance again recently.

A group of chinese tourists enjoy the singing sands on the edge of Mingshashan as dusk settles over the Dunhuang oasis; behind the stony Taklamakan lurks menacingly, kept temporarily at bay by the irrigation systems built up with the hard toil of local people over countless generations.

The trade route itself is also being reopened. The sluggish trade between the

peoples of Xinjiang and those of the Soviet Union has developed quickly; trade

with the C.I.S. is picking up rapidly with a flourishing trade in consumer items

as well as heavy industry. The new Central Asian republics had previously

contributed much of the heavy industry of the former Soviet Union, with a

reliance for consumer goods on Russia. Trade with China is therefore starting to

fulfill this demand. This trading has been encouraged by the recent trend towards

a `socialist market economy' in China, and the increasing freedom of movement

being allowed, particularly for the minorities such as those in Xinjiang. Many

of these nationalities are now participating in cross-border trade, regularly

making the journey to Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan.

Restoration and Tourism

Since the intervention of the West last century, interest has been growing in

this ancient trade route. The books written by Stein, Hedin and others have

brought the perceived oriental mystery of the route into western common

knowledge. Instilled with such romantic ideals as following in the footsteps of

Marco Polo, a rapidly increasing number of people have been interested in

visiting these desolate places. Since China opened its doors to foreign tourists

at the end of the 1970s, it has realised how much foreign currency can be

brought to the country by tapping this tourist potential. This has encouraged

the authorities to do their best to protect the remaining sites; restoration of

many of the sites is presently underway. The Mogao grottoes were probably the

first place to attract this attention; the Dunhuang Research Institute has been

studying and preserving the remains of the grottoes, as well as what was left of

the library. Restoration is presently underway; the outside of the grottoes was

faced in a special concrete to prevent further subsidence, and some of the

murals are being touched up by a team of specially trained artists and

craftsmen.

A corner of the sunday market in Kashgar, the former crossroads of Asia, where the the spirit of the Silk Road lives on. Every week, the different peoples from Western China are joined by countless others from Pakistan and the former Soviet Republics in one of the world's busiest and most lively open-air markets. In this quiet corner a Uygur trader sells spices, many of which have no doubt come from much further afield.

Although Xinjiang is opening up, it is still not an easy place to travel

around. Apart from the harsh climate and geography, many of the places are not

fully open yet, and, perhaps understandably, the authorities are not keen on

allowing foreigners to wander wherever they like, as Hedin and his successors

had done. The desolation of the place makes it ideal for such aspects of modern

life as rocket launching and nuclear bomb testing. Nevertheless, many sites can

be reached without too much trouble, and there is still much to see.

Conclusions

From its birth before Christ, through the heights of the Tang dynasty, until

its slow demise six to seven hundred years ago, the Silk Road has had a unique

role in foreign trade and political relations, stretching far beyond the bounds

of Asia itself. It has left its mark on the development of civilisations on both

sides of the continent. However, the route has merely fallen into disuse; its

story is far from over. With the latest developments, and the changes in

political and economic systems, the edges of the Taklamakan may yet see

international trade once again, on a scale considerably greater than that of

old, the iron horse replacing the camels and horses of the past.

BOOKS

Peter Hopkirk, `Foreign Devils on the Silk Road', Oxford U.P., 1980.

oliver@atm.ch.cam.ac.uk