Final year students contribute to diverse media projects

As part of their final year dissertation, Media and Cultural Studies students have the option of creating media that intersects with particular research interests or aims they have developed during their time at Lancaster. This media project dissertation option was first launched in 2019-20, in response to student feedback, and to date students have created everything from Extended Play music albums and fashion lookbooks to family board games, slash videos and short animations. This diverse work created this year was shared at an online media showcase in June 2020, and a few examples are highlighted below.

Niamh Harrison:

At the centre of Niamh Harrison’s Media Project Dissertation was a podcast episode she produced, as part of a fictional podcast series titled ‘Clarity’. The episode investigated so-called ‘slacktivism’ and its impacts upon different social groups. In her dissertation, Niamh writes that slacktivism ‘evokes an image of inactively participating within digital social movements’ and ideas about forms of ‘amateurish activism’. The podcast invited four guests to critically explore different understandings of slacktivism and whether slacktivism leads to unity or division between social groupings. This included examining who might be excluded from slacktivist practices, slacktivism’s legitimacy, and motivations for performing slacktivism. Through doing this research, Niamh concluded that, overall ‘slacktivism is miscategorised’, with participants highlighting the need for a variety of roles within forms to achieve revolutionary change. ‘Slacktivism’, she writes in her accompanying critical reflection on the podcast and its production, ‘may be employed as a valuable tool for social issues, but it must be applied in real-life spheres to promote genuine change’.

Nurin Rashdan Fitri:

As she tells it, Nurin’s dissertation project started when a friend introduced her to the concept of a ‘third culture kid’:

“Van Reken and Pollock’s (2017) book ‘Third Culture Kid’ described the unique yet similar cross-cultural and highly mobile lifestyle that I have experienced during my childhood. In their words, I was “a child or person who has spent a significant part of his or her development years outside the parents’ culture” (ibid) and transitioning into adulthood I am considered an ‘Adult Third Culture Kid’. Later on, the book discusses one of the challenges faced by ATCKs (and TCKs alike) about the effects of new communication technology on sustaining the many relationships that adult TCKs fostered growing up as a child abroad... This inspired my project into finding more deep, nuanced insights about the use and the effect of using the features and tools of the Internet and social media to construct and explore ATCKs sense of identity and belongingness in the public sphere (McLuhan, 1964) and online communities.”

In addition to creating her own blog posts and video interviews with people who were already creating and leading ATCK communities online, Nurin also contributed to some of these communities by sharing her own stories on an episode of the podcast Floaters.

Evelyn Sun:

It was not contributing to an existing media community, but envisioning future ones that inspired Evelyn’s project, which started from an understanding of utopia: “utopian literature is essentially a kind of “social commentary”, the social criticism of the reality and social implication of the possible, by means of social rearrangement. By extension, the essence of utopia is to invite us to question the assumptions of our own society”.

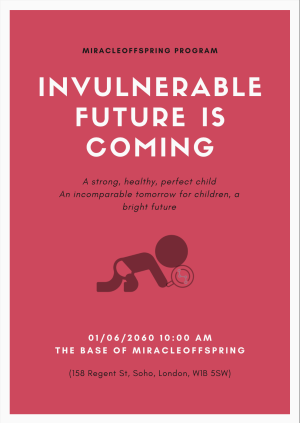

Evelyn’s media practice involved creating a pair of contrasting speeches, both delivered in the year 2060 in a society where technology had moved on considerably to allow for technologically-perfected offspring gestated outside of human bodies.

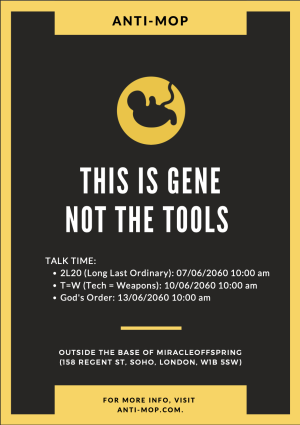

She first invited readers to imagine being part of the wealthy elite, listening to a corporate pitch for new ‘miracle offspring’ technology. But her second speech, presented in the style of public activist protests, highlighted the inequalities and injustices that a world with such advanced technology might still hold:

“What should we say to our children? They are the most natural thing in this world, they are the real human beings? But the real reason is that their parent cannot afford the expensive genetic programming fees, their parents are not even qualified to walk into the building behind them, so they can only stand here to do this resistance movement like today, which is under police supervision as if we’re going to break down and run into the building at any moment. Are we going to say that to our children? Will you say that? Will you? Will you?”

By evocatively painting a future world (where incidentally Covid-19 isn’t the last pandemic), Evelyn accomplished what great creative work often does – create an opportunity to shift the way we think about both aspects of our own personal lives and the cultural communities around us.

We can’t wait to see what kinds of projects our next cohort of students create.

Back to News