The Virginia Company and the Attempted Settlement of the East Coast of America

The Virginia Company was a joint-stock company established by James I and VI by charter in 1606 to colonise and exploit the East coast of America. The name was applied to it later: there were originally two groups of stockholders, the London Group ‘called the First Collonie’, and the Plymouth Group, which was composed of ‘sondrie Knights, gentlemen and others of the cities of Bristoll, Exeter, the towne of Plymouth, and other places, called the Second Collonie’. The Plymouth colony was unsuccessful, and lapsed after a year.

The London Company established the settlement of Jamestown, but despite the efforts of their leader John Smith, who deployed the slogan ‘those that don’t work, don’t eat’, they ran into difficulties with supplies and with the Powhatan tribe. Smith was injured in a gunpowder explosion, and returned to England in October 1609. The chapter of disasters continued, and during the winter of 1609–1610 about 440 of the 500 current inhabitants starved to death or died of other diseases. They may have resorted to cannibalism to keep themselves alive. A relief expedition by Lord de la Warr, their new governor and major shareholder, rescued the colony from extinction.

It was rescued financially by the cultivation of a new strain of tobacco obtained from Trinidad by the planter John Rolfe, who had arrived in 1610 on the Sea Venture from Bermuda,

where they had been shipwrecked. This tobacco was more palatable to the English taste than the native variety, and the colony soon came to depend on it for its financial survival. Rolfe,

whose wife and child had died in Bermuda, also took the diplomatic step of marrying Pocahontas, the daughter of chief Powhatan, and there was peace between the Indians and the settlers for a while. In 1616

they went to England the the suggestion of the Company on a publicity mission. Pocahontas (now Rebecca) was a great success, but died in 1617 just before embarking again for Virginia. Rolfe returned and

continued tobacco-farming. He died just before the 1622 Massacre.

It was rescued financially by the cultivation of a new strain of tobacco obtained from Trinidad by the planter John Rolfe, who had arrived in 1610 on the Sea Venture from Bermuda,

where they had been shipwrecked. This tobacco was more palatable to the English taste than the native variety, and the colony soon came to depend on it for its financial survival. Rolfe,

whose wife and child had died in Bermuda, also took the diplomatic step of marrying Pocahontas, the daughter of chief Powhatan, and there was peace between the Indians and the settlers for a while. In 1616

they went to England the the suggestion of the Company on a publicity mission. Pocahontas (now Rebecca) was a great success, but died in 1617 just before embarking again for Virginia. Rolfe returned and

continued tobacco-farming. He died just before the 1622 Massacre.

By 1621, the Company was in financial difficulties, partly due to the Government's attitude on tariffs which made it difficult for them to export their tobacco crop. In 1622, the Massacre led to ‘"perpetual war without peace or truce" ’ with the Powhatan Indians, with the aim of wiping them from the face of the earth. In 1624 the Crown took control of the territory as a crown colony.

John Smith meanwhile publicised the colony and his role in it in A True Relation of Virginia (1608), and The Generall Historie of Virginia, New-England, and the Summer Isles (1624).1 He describes the country, its natural resources, and the interesting customs and attire of its inhabitants:

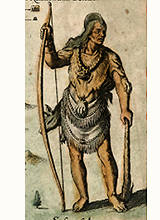

We haue seene some vse mantels made of Turky feathers, so prettily wrought & woven with threads that nothing could be discerned but the feathers. That was exceeding warme and very handsome. But the women are alwayes covered about their middles with a skin, and very shamefast to be seene bare. They adorne themselues most with copper beads and paintings. Their women, some haue their legs, hands, breasts and face cunningly imbrodered with divers workes, as beasts, serpents, artificially wrought into their flesh with blacke spots. In each eare commonly they haue 3 great holes, whereat they hang chaines, bracelets, or copper. Some of their men weare in those holes, a small greene and yellow coloured snake, neare halfe a yard in length, which crawling and lapping her selfe about his necke oftentimes familiarly would kisse his lips. Others weare a dead Rat tyed by the taile. Some on their heads weare the wing of a bird, or some large feather with a Rattell ... Others a broad peece of Copper, and some the hand of their enemy dryed.

Illustrated with images cannibalised from de Bry’s engravings of John White’s watercolours of the Roanoke Native Americans seen on Sir Richard Grenville’s 1585 expedition,2 these descriptions make thrilling reading for the armchair traveller, and may even have encouraged some adventurers to try the voyage for themselves. Thomas Hariot’s earlier A Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia (1590), for which the de Bry engravings were first made, is equally attractive and possibly slightly more temperate. 3 Neither of them suggests the possible horrors in store for the settlers.

1. London: Printed by I[ohn] D[awson] and I[ohn] H[aviland] for Michael Sparkes, 1624. Return.

2. John White (c.1539–c.1593) accompanied Grenville on his first expedition to Roanoke. His water-colour drawings of the Native Americans were engraved by

Theodore de Bry in 1590 for Harriot’s Briefe and True Report, and become a staple of illustrated books on America and on world costume. He returned to Roanoke

in 1587 as its governor with over 100 would-be colonists including his daughter and her husband; they found that the first colonists had all been killed by the Indians. In the late autumn, with the colonists

beginning to run out of provisions, he returned to England for supplies. The journey was disastrous, and White arrived in England to find that all shipping had been frozen because of the threat of the Armada.

When he finally managed to return in 1590, the colonists including his daughter and 3-year-old grandaughter, had vanished, leaving a message carved on a tree which suggested that they had gone to a

neighbouring island. The weather got worse, and the search for them had to be abandoned. White returned to England, and never discovered what had happened to them.

For a comparison of White's drawings and de Bry's (very Europeanised) engravings, see the Virtual Jamestown

website. Return.

3. Thomas Harriot (c.1560-1621) was on the 1585 expedition to Roanoke. He was Raleigh's mathematics tutor, and specialised in navigation. He could also speak Algonquin, which he had learned from two Native Americans, Manteo and Wanchese, who had been brought to England. He had learned a great deal about their native land and its people before setting sail. He wrote the Briefe and True Report on his return. He is rumoured to have introduced the potato into Britain. Unfortunately he had also learned the habit of smoking tobacco, and died of cancer of the nose. He was a proficient practising astronomer, and in 1609 bought a telescope with the help of which he drew a detailed map of the moon, several months before Galileo. Return.

Close window to return.