Milking it for all its worth: sourcing plastic packaging free alternatives

Posted on

Figure 1: Milk delivery.

For some of us milk drinkers (plant-based or diary), the dwindling supply of milk presented us with a choice – do without, find a plastic-free alternative, or make your own.

Conversations ranged from “well it is only a month, I can do without” to the unbearable prospect of not being able to enjoy a cup of tea or coffee with milk (and of course, for those of us that did not drink milk this was not a problem). The path of least resistance seemed to be to replace plastic milk bottle with glass, which for some represented a return to happy memories of childhood when the milk was waiting on the doorstep every morning (and a race against the birds pecking the foil lids). Others managed to source their milk from a local vending machine, where bottles cost a euro and could be refilled.

Sourcing alternatives

A quick online search “is glass better than plastic for milk bottles?” provided 6.3 million hits. After an hour or so of reading, our conclusion was that glass replacements appeared a relatively sound choice with the following caveats:

- the bottle should be reused at least 20 times (depending on the source you read),

- produced from non-renewable energy sources

- if delivered, ensure it is local, and that the milk delivery service operates a rinse and collect service.

Biodegradable packaging options were also investigated (with over 3.5 million hits), though it appeared much harder to get to grips with which milk products we could purchase - the top pages appeared to focus on the manufacturing of the alternative packaging [something we will keep investigating].

Sourcing success varied within the team. A quick SOS message to a holidaying neighbour led to home delivery being arranged for one of us, although with the accompanying realisation that delivered milk in glass bottles cost 44% more than that purchased in plastic bottles in the supermarket. Visiting family in Italy, another team member walked 5K in the sweltering heat to the local raw milk vending station, only to discover it was no longer there, and the supermarket and local shop offered no plastic-free alternative (despite being surrounded by farms in the vicinity). The initial assumption is that the machine has been removed due to the practicalities of having to boil the milk before use and the longevity of the milk lasting up to three days [our investigations continue…watch this space!]

For several of us, the milk ran dry, and one member of the team made their own oat milk, which was then stored in a reused glass bottle. For those interested in making oat milk, you need a cup of rolled oats, 4 cups of water, a high-speed blender and a clean T-shirt. But be warned, over-blending can make the oat milk slimy! The first batch did not taste great. Persistence was key, the second batch had cashew nuts added for the improved taste, and created a newfound enthusiasm to keep experimenting until the recipe was perfected [note – oats and cashews were sourced pre-plastic free July – the oats came out of a cardboard box, but the cashews came out of a plastic packet].

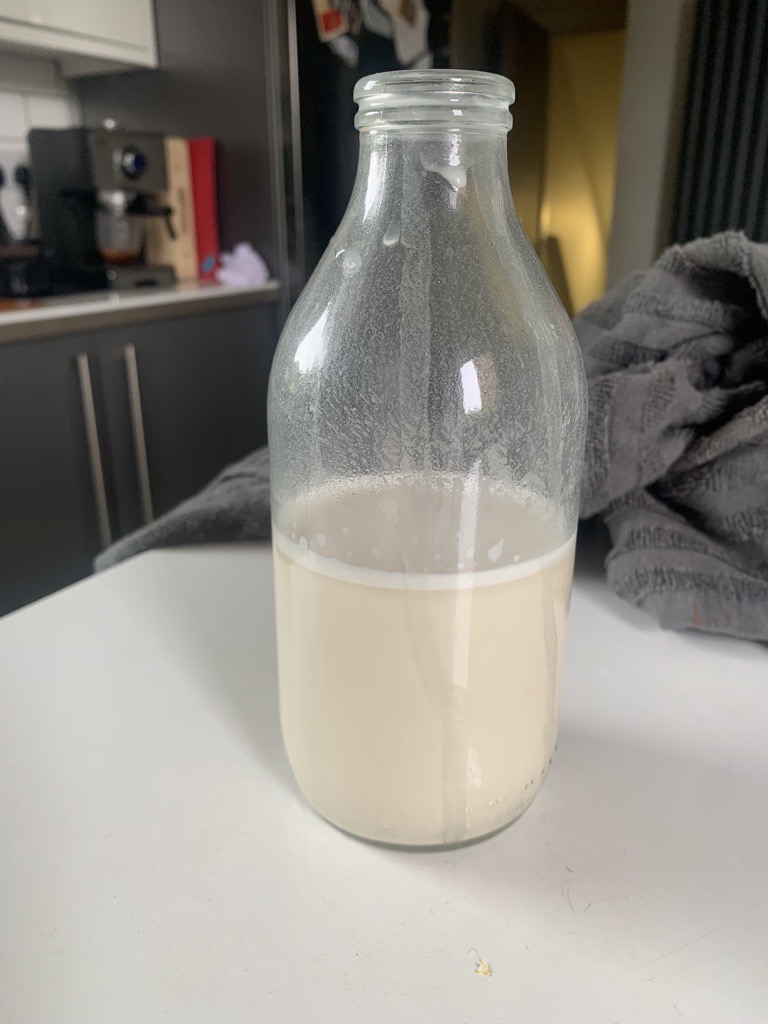

Figure 2: Homemade oat milk.

For another team member, the milk drought lasted less than 30 minutes. This member forgot to remind their husband that they would go without milk (rather than buy in plastic packaging). Husband popped out to get the newspapers, and so too did plastic packaging appear in the fridge.

For the successful plastic packaging/glass swap, the milk arrived on the doorstep. One thing not really anticipated was the fact that the bottles occupy a different space in the fridge, which meant fridge reconfiguration was required, especially to find space that was secure for these fragile and slippery bottles.

What has this meant for us as consumers and our everyday lives?

Just over a week into Plastic Free July has heightened our sensitivity towards our own consumption of food plastic packaging. To make changes we have started to gain an enriched appreciation that our consumption choices need an investment of time, a range of options to cater for our diverse needs, the right infrastructure, and a certain level of financial freedom.

Time played a crucial factor; time to research online, to visit supermarkets, to communicate with others (in and outside the household), to learn new skills (oat milk creation), or to walk to source the milk. Clearly, investigating, arranging, making, or sourcing alternatives requires a conscious decision to make space within already busy schedules. And these investments of time may be ongoing since we were not always successful in our efforts (e.g., milk station in Italy or the first attempts at oat milk). Further ongoing investments are attached to bill payments for deliveries, remembering to leave the bottles outside, homemade milk-making, and time to walk and source the waste. As consumers, we recognised that we found the time because we are curious, concerned and enthused about the topic of plastic packaging – for those of us making milk changes, doing so was not problematic.

Catering for diverse needs – we recognised that some of the changes we made are tied in with ableism; we were able to read, walk, create, and pick up the glass bottles. For most of the team, the swaps were managed with relative ease, but what if we were unable to pick up those glass bottles? The plastic packaging alternatives are light, easier to grab hold of, and less likely to smash/leak if knocked over. So, is glass the answer here? If the plastic milk bottle, for instance, disappears, who is then included and excluded from the product purchase?

The right infrastructure must be in place, whether that is a digital infrastructure to research and order online, a telephone network to connect with the local organisation, organisation attached to a reuse/recycling infrastructure (rinse and collect), the kitchen equipment to make your own or a supermarket with the appropriate distribution and supply chains. As consumers, we were reliant on, or took for granted, the fact that we had access to all these different infrastructures to educate ourselves on plastic packaging-free alternatives, contact the local organisations to make our new purchases, had faith that the reuse/recycling systems worked, home infrastructures that held the right ingredients and equipment to make milk, and/or access to supermarkets and their supply chains to offer the products. This question of infrastructure raises more questions about access -- what about those consumers who do not have access? what do they do? do they already use plastic packaging-free alternatives? Is that choice taken away? If it is, does it matter?

Financial ability - from our experience, having milk delivered in glass bottles adds a 44% price increase to milk purchased from supermarkets in plastic containers. Clearly, the consumer has to have the financial resources available to make this choice. Despite feeling great about supporting a local business, where money is tight, then the costs of making these changes can be prohibitive. Costs add up too, especially if you go down the route of making your own milk alternatives, which may require the purchase of new equipment such as that high-speed blender to make oat milk [even the non-electrical options require a pestle and mortar and physical strength to grind/crush the oats – taking us back to the points earlier about time and ableism].

So far, Plastic Free July has provided the impetus, focus and desire to make changes, and we are developing an enriched awareness of what it means to go “plastic-free”. But, as our experience of the challenges associated with moving to plastic packaging-free milk shows, we can see a whole range of complexities attached to everyday consumption practices, and this is for a team of people who are in relatively privileged positions to make some of those changes. Imagine what it’s like for consumers who do not have such resources (financial, delivery options, skills, time, energy, physical ability) available to them.

Authors: Dr Alison Stowell, Prof. Maria Piacentini, Dr Matteo Saltalippi, Dr John Hardy, Dr James Cronin, Dr Charlotte Hadley, Prof. Linda Hendry, Dr Alex Skandalis, Dr Savita Verma.

Related Blogs

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed by our bloggers and those providing comments are personal, and may not necessarily reflect the opinions of Lancaster University. Responsibility for the accuracy of any of the information contained within blog posts belongs to the blogger.

Back to blog listing