ESG and sustainability – different but related ideas

Posted on

© Image by Geralt on Pixabay

© Image by Geralt on Pixabay

ESG (environmental, social and governance) are three letters that seem to be on the lips of everyone in the corporate and investment communities. Whilst historians will point to the many threads that have created the ESG narrative, a key development in making ESG ‘mainstream’ was the 2005 Freshfields Report commissioned by the United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative (UNEPFI). This concluded that integrating ESG considerations into investment analysis is “clearly permissible and is arguably required”.

ESG has advanced significantly since then. Not least in the last two to three years, driven by a combination of societal concerns, action on climate change through the Task-Force for Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) and the EU Non-financial reporting directive. So-called ESG investing has become a growing trend and is becoming embedded inside companies beyond the investor relations team. In these respects, ESG is a corporate and finance industry response to societal desire for sustainable development.

The rise of ESG has somewhat overshadowed sustainability itself. Sustainability is a broader concept which starts from an understanding of a ‘safe operating space’ for society, comprising environmental thresholds and societal foundations - issues such as climate change, inequality and nature. A sustainability lens requires organisations to understand their impacts upon these earth systems and society and mitigate and remediate any impacts upon them.

There is a need to be clear about the relationship between ESG and sustainability. These concepts are often conflated and used to mean the same thing, engendering vigorous debate (or, should we say, a row) between their proponents. It is our view that these concepts are distinct but connected, and that they both have their place. The purpose of this blog is to demonstrate the important ways in which they differ.

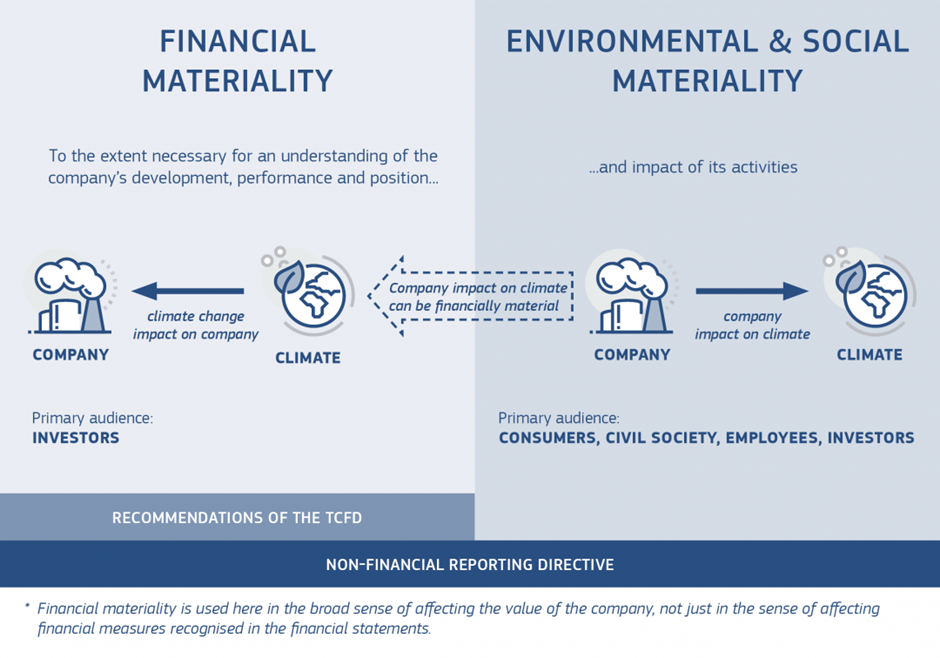

A key concept here is ‘materiality’. Materiality is all about the importance or significance of an issue. In discussing ESG and sustainability, the term ‘double materiality’ - championed by the European Union – is used to talk about the significance of the impacts business has on earth systems and society, and also the significance of these earth systems and societal issues on the business.

These two flows of materiality have been characterised as ‘inside-out’ and ‘outside-in’ impacts, built around a common core set of issues (see Fig 1). ‘Inside-out’ describes our common understanding of how companies and organisations impact society and the environment. (in the figure below, ‘Environmental and social materiality’). For the last twenty years this has been the focus of corporate sustainability programmes on (for example) responsible sourcing addressing human/labour rights and the environmental impacts of supply chains. Sustainability programmes have sought to reduce those impacts, and more recently begun to focus on how to make a positive impact (for example, through regenerative agriculture and initiatives such as being a living wage employer). The consequences of the inside-out (sustainability) lens are significant – they relate to lives being lost, livelihoods destroyed, forests being razed. They also involve the concepts of thresholds, planetary boundaries and systems.

Figure 1

The double materiality perspective of the Non-Financial Reporting Directive in the context of reporting climate-related information (Source: https://sustainabilityknowledgegroup.com/commission-guidelines-on-non-financial-reporting-supplement-on-reporting-climate-related-information-the-key-takeaways/tfcd/)

The double materiality perspective of the Non-Financial Reporting Directive in the context of reporting climate-related information (Source: https://sustainabilityknowledgegroup.com/commission-guidelines-on-non-financial-reporting-supplement-on-reporting-climate-related-information-the-key-takeaways/tfcd/)

Outside-in impacts, or financial materiality, on the other hand are the basis for ESG. The question is how will an earth systems issue, for example climate, impact the company and its enterprise value (total financial value). Investors need to know this information to assess the value of the company, and to understand what a company’s response is and whether it can mitigate these impacts. This understanding guides investment decisions. The consequences of an ESG lens on materiality is therefore on share prices, and consequently the value of pensions.

The worrying thing is when the two concepts are conflated, the aims of each approach will be undermined. And, the bigger worry is that approaching sustainability challenges through only an ESG lens lowers the bar.

For example: TCFD is concerned about financial materiality – the outside in perspective. Most companies, having disclosed their climate related financial risks, offer up their Net-Zero Plan as a response. Whilst that certainly addresses some of the risks, managing for net-zero (i.e., a sustainability-led approach) is not the same as addressing the financial risks. To illustrate this; carbon pricing (a tax on greenhouse gas emissions) is seen as crucial for helping society get to Net-Zero, and most corporate Net-Zero plans do discuss the need for a carbon price. However, the financial impact on companies of carbon prices at a level that are needed for Net-Zero are viewed as too disruptive for many sectors. Mitigating this financial risk would imply that a firm might wish to delay carbon pricing legislation until it can be financially accommodated. These are very different perspectives to be working with.

Recent real world examples of the confusion on ESG and Sustainability

- A recent survey by the National Association of Corporate Directors found that 59% of US board directors think ESG data will receive as much scrutiny as financial reporting in the next three years. Presumably they mean sustainability data. ESG data is all about corporate financial values – surely more than 59% of board directors care about that already.

- A recent job advert from a major UK company sets out its sustainability credentials, but then deviates to talk about ESG “At [xxx], caring about the impact we have on the world around us is part of who we are, and this is a stand-out opportunity for an experienced ESG communications professional to tell that story and take a lead in the development and co-ordination of our ESG communications activity.” Does the company want to communicate all the good things its doing to reduce its impact upon earth systems and society, or just to explain how it is addressing its fiduciary duty.

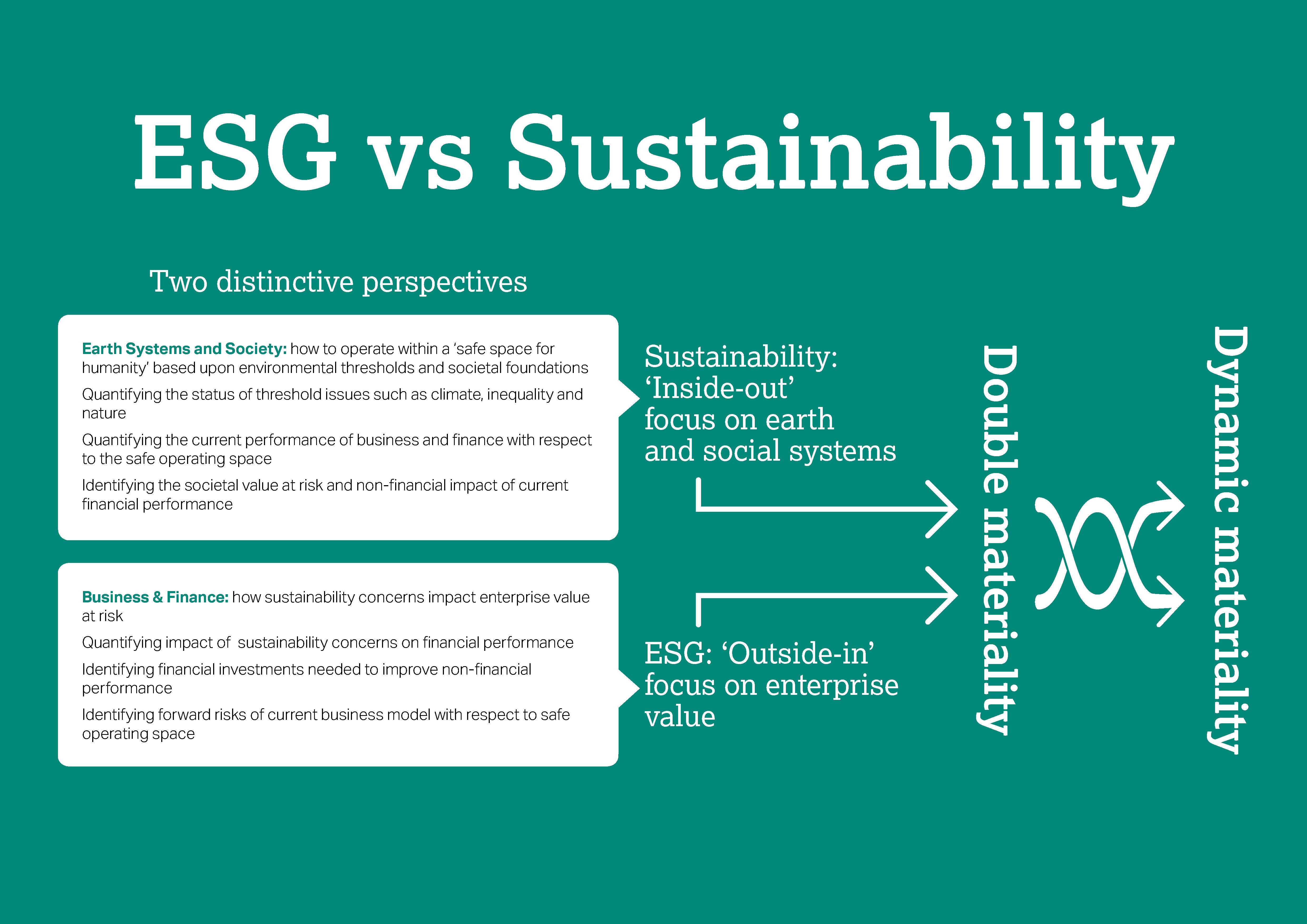

We do believe that ESG has been, and can continue to be, an important driver for societal progress. And we do need to make it deliver what it can. Part of that will be developing better guidance for boards, regulators, and sustainability professionals to translate ecological and social justice issues into questions that are salient for business. It will be about evolving from double materiality to dynamic materiality – recognising that one affects the other. See Figure 2 for an example of how this could be communicated.

Figure 2

At the same time, we also need to understand ESG’s limitations. In particular, we will need a way for investors to deal with the system level risks and thresholds that ESG is not able to articulate reliably.

It will also be about not conflating the two, not sowing confusion, keeping sight of the various ways that are needed to drive forward progress. This is the current challenge for sustainability professionals, ESG professionals, boards and accountancy firms.

In our next blog, we will build on these ideas to talk about business and biodiversity perspectives.

Jan Bebbington is the Director of the Pentland Centre for Sustainability in Business

Duncan Pollard is an Honorary Professorial Fellow in the Pentland Centre for Sustainability in Business

Related Blogs

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed by our bloggers and those providing comments are personal, and may not necessarily reflect the opinions of Lancaster University. Responsibility for the accuracy of any of the information contained within blog posts belongs to the blogger.

Back to blog listing