Explosive London housing bubble will spread to the rest of the UK

12 June 2014

12 June 2014

Escalating house prices are no longer just a London quirk – research by a team of LUMS economists supports the view that the housing market is the biggest issue for the UK economy.

It is easy to see why people are talking about the possibility of another UK housing bubble, just six years after the last crash. House prices in London, for instance, have gone up 17% in the past year alone.

Many feel rising prices are the normal results of increased incomes, a shortage of housing supply, or other perfectly logical factors. However, our research at Lancaster University suggests this may not be the case. The findings indicate that a housing bubble is developing in London, with the risk of spreading to the property markets in the rest of the UK.

A bubble is defined as a prolonged departure of house prices from reasonable causes, typically due to expectations and speculation on a market where prices are going to keep on rising. Critically a bubble involves prices growing fast, showing “explosive” behaviour.

Bubbles are more dangerous than simple price rises as they have the potential for a sudden crash, leaving homebuyers with large mortgages and negative equity.

We have gathered data on house prices across the UK since start of the housing boom under Margaret Thatcher in the 1980s. We then analysed the data using a statistical method recently developed by Yale economist Peter Phillips to identify bubbles, known as the Backward Supremum Augmented Dickey-Fuller, or BSADF. Using the BSADF were we able to identify periods during which the housing market experienced explosive price increases which may not be explained by the normal factors that determine house prices.

The following graphs show there is indeed evidence consistent with a house price bubble in London, and that it is likely to spread nationally.

The first graph below shows the estimated BSADF figure for the London and UK house markets since 1983. The blue line is the “critical value” – the point above which we can be sure price rises are no longer linked to normal factors such as increased incomes. Periods when the BSADF crosses above the blue line are indicative of explosive behaviour.

BSADF statistic over time for UK housing market Paya et al

BSADF statistic over time for UK housing market Paya et al

As the graph shows, London was in “bubble territory” from late 1985 until early 1990 and again from late 1999 until the third quarter of 2008, when the financial crisis hit.

London’s line has just gone back above the blue line, in the first quarter of 2014, so the capital’s house prices just turned explosive.

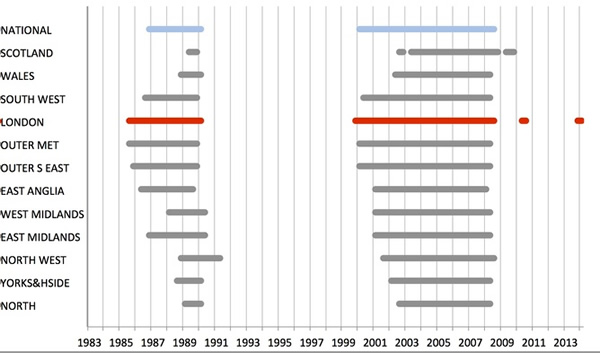

The next graph shows when the price rises were above the bubble threshold line for each region in the UK since 1982. Importantly there’s strong evidence of a precedent for London and its metropolitan area leading all other regions, and the likelihood of the same kind of ripple effect in the rest of the UK.

Explosive house price rises by UK region  Both previous housing booms began in London and spread from there. Paya et al

Both previous housing booms began in London and spread from there. Paya et al

The ripple effect is simply the result of buyers looking for more affordable property elsewhere. Armed with positive equity, money pours into regions around London, and then further afield, increasing demand and prices.

Intuitively, price rises in London cause price rises in the surrounding areas, as people who cannot afford to buy a house in the capital settle for their second-best choice. And buyers bid up prices to profit from the price gap between London and surrounding regions.

The data is consistent with Mark Carney’s view that the housing market is the biggest issue for the economy. It is easy to see why housing will be a central feature of the banking sector’s next “stress test” carried out by the Bank of England – rapid price rises are no longer something the rest of the country can dismiss as a London quirk.

Image Nate Edwards | CC BY-NC

![]()

| Follow the discussion via The Conversation comments |

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article. They also have no relevant affiliations.

The opinions expressed in our Comment and Analysis articles and in any attached comments are personal, and may not reflect the opinions of Lancaster University Management School. Responsibility for the accuracy of the information contained within these articles resides with the author.