We have been renowned for groundbreaking historical research and teaching since 1964.

From the founding of the Department

1. Origins and early years

‘From the top downwards, the young idea is at the helm.’1 That is how the Lancashire Evening Telegraph summed up the state of things at Lancaster University during the first weeks of our first term in the autumn of 1964. Classes were then being held in the old Gillow and Waring factory on St Leonard’s Gate in the city centre, but an atmosphere of innovation prevailed. ‘The new university’, we read, ‘is being run by people in the prime of life, not old timers. Most of the staff are in their twenties, thirties and forties, and the impression is […] one of youth brimming with new, unstuffy ideas.’2

That quotation fits a narrative that is writ large in the historiography of the ‘plate-glass’ era in British higher education. The expansion of the university sector in the decades after the Second World War was driven by the demand to increase university places. That was the mission spelled out in the Robbins Report on higher education in 1963: to ensure university places would be ‘available to all who were qualified for them by ability and attainment’.3 For all that, though, the nation’s newly chartered universities (that Shakespearean-sounding seven: Sussex, Essex, Norwich, Kent, Warwick, York and Lancaster) embraced university expansion as an opportunity for curricular innovation.

Lancaster might not have pressed as far as other pioneering institutions, such as Keele University, in requiring students to specialise in multiple subjects. Still, our University’s mission in its first years involved drawing up ‘new maps of learning’.4 Those new maps were not just devised by junior staff. As Marion McClintock has pointed out, Lancaster’s new maps were largely the work of older men, including the sixteen original department heads, who were handpicked by Charles Carter, our first Vice-Chancellor, and the members of our Academic Planning Board.5

One member of that Board, Bruce Williams, expressed reservations about History becoming a central discipline in the (then) newly forming arts faculty. According to Williams, History’s place at Lancaster would ‘depend in some measure on getting historians who really understand what a civilisation is.’6 Lancaster historians, in so many words, would need to tend to more than their individual areas of expertise to remain relevant; they needed to be broadminded individuals who were capable of thinking across different orders of knowledge. Thankfully, our first Professor of History, Austin Woolrych, was more than up to that demand.

Notes

1 D. Sheppard, ‘It’s Such a Go-Ahead University’, Lancashire Evening Telegraph, 18 November 1964.

2 ‘Such a Go-Ahead University’.

3 Qt. H. Perkin, New Universities in the United Kingdom (OECD, 1969), p. 103.

4 M. Beloff uses this phrase in The Plateglass Universities (London: Secker and Warburg, 1968).

5 M. McClintock, Shaping the Future (University of Lancaster, 2011).

6 M. McClintock, University of Lancaster, Quest for Innovation: A History of the First Ten Years, 1964–1974 (Lancaster, 1974), p. 130.

2. 'Three men and a boy'

Austin Woolrych was one of the sixteen department heads who formed the University’s Shadow Senate during our fledgling years, and he remained History’s Head of Department for a full two decades. When he eventually stood down in 1983, an endearing tribute in one university newspaper jested that he had been selected on account of three things. The first was ‘the diversity of his previous employment’, which had included a stint as a sales clerk at Harrods department store.1 That job was followed by his service with the Royal Armoured Corps in north Africa, where he rose to the rank of Captain, and later, his academic post at the University of Leeds, where he rose to the rank of senior lecturer. The second and third things that allegedly earned Woolrych the job were his academic achievements, including his book Battles of the English Civil War (1961), and his ‘reputation as a vigorous and imaginative administrator.’2

Woolrych played a leading role in drawing up the 'new maps of learning' that guided our Department in its early years. Under his watch, History thrived. Two-thirds of the nearly 300 undergraduates who enrolled for studies at Lancaster in 1964 studied History in their first year, and they were taught by members of a department that comprised (what Woolrych affectionately termed) ‘three men and a boy’.3 Woolrych was one of the men; the other two were Keith Bell and David Hamer. Both Bell and Hamer only spent a few years at Lancaster. Bell was a politically engaged historian who appears to have left academia in the late 1960s due to health issues.4 Hamer, for his part, was a modern historian and a New Zealander who had studied at Oxford University. He taught in our Department from 1964 to 1970, when he took up a position at the University of Auckland.

So, in a sense, Woolrych, Bell and Hamer were our founding fathers. But what about the boy? That was a youthful Marcus Merriman, who at the tender age of twenty four was appointed temporary assistant lecturer: his first proper job.

Merriman proved much more than temporary. He remained a loyal member of our History Department until he died in 2006. Across those 'four decades', as Michael Mullett (who joined the Department in 1971) has written, 'Marcus proved himself a superb teacher – and an actor to his fingertips. He displayed idiosyncratic brilliance in the classroom with his carefully researched, but amazingly theatrical, lectures, complete with displays of canonry and gunpowder.'5

The writing Merriman left behind attests to his sense of humour. As proof, consider the following anecdote, which he recalled when looking back on his first year at Lancaster:

'If before age 24 I had no boss, now, if I bungled (and I seemed to, all the time), there was someone to bawl me out. The nervousness of that subservience was all-pervasive and excruciating at first: “Marcus, do call me Austin” received a reply, “Yes, Professor”. Conversely, if I did OK, then my boss could praise. I well remember Austin bouncing into my office one day to tell me I had won a gold medal prize (sounds like an award for excellent flour). He’d been waiting all day to see me, so much so, he’d pestered Angela, our secretary, as to where-ever might I be. Angela had a good idea, having also been at Keith Bell’s party the night before.'6

Notes

1 ‘Founding Father’, Fulcrum, 85 (23 June 1983), 4; Lancaster University archive, UA.1/9/1/2. I am grateful to Marion McClintock for providing access to this item and other items from the University archive.

2 ‘Founding Father’.

3 ‘Founding Father’.

4 See Stanley Henig, ‘MP puts the record straight’, Lancaster Guardian (3 November 1967), 12. I am grateful to Alan James for this reference.

5 Michael Mullett, 'Dr Marcus Merriman', The Guardian, 10 April 2006 <https://www.theguardian.com/news/2006/apr/10/guardianobituaries.obituaries1> [accessed 19 October 2024]

6 Marcus Merriman, ‘That bloody first year’, Lancaster Comment, 45 (7 November 1974), 9–12; Lancaster University archive, UA.1/ 9/3/14.

3. 'Ambitious and spirited academics'

Marion McClintock has observed that the founding heads of Lancaster’s first sixteen departments ‘came with strong views about the direction of teaching and research that their disciplines should take’, and they were given licence to appoint ‘younger and less experienced staff’ to carry their views forward.1 That certainly rings true in Woolrych’s case. It has been observed that, in contrast to the trend evident at other plate-glass universities, where History was increasingly linked with the social sciences, Woolrych ensured that, at Lancaster, it was also linked with the arts.2

John Morrill has remarked that, as a scholar, Woolrych favoured empirical research to ‘methodologically driven study’, and that influenced the sort of History curriculum he wanted and the sort of people he wanted to teach it.3 That is not to say that Woolrych’s sense of the discipline was narrow. He saw to it that Lancaster offered both medieval and modern history in addition to ensuring that teaching covered subjects beyond British and European history. Woolrych also saw to it that there would be a strong place at Lancaster for social history, as well as the history of science and the regional history of the North West of England.

Still, the empirical leanings evident in Woolrych’s scholarship are equally evident in the more senior appointments he made during Lancaster’s first five years. Those appointments included then up-and-coming figures like Harold Perkin and Joseph Shennan (both of whom arrived in 1965), John Duncan Marshall (who joined the Department in 1966) and Geoffrey Holmes (who joined in 1969). None of these scholars came to Lancaster directly from London or Oxbridge. Like Woolrych, they had previously been at northern colleges and universities. Holmes, for his part, had been at Glasgow University, and Marshall had been a principal lecturer at Bolton Training College. What is more, like Woolrych, all these appointments were committed teachers, and they helped shape the academic and intellectual environment for the other, more junior colleagues who joined the Department over the course of its first decade, many of whom did come from Oxbridge.

One of those younger colleagues, Martin Blinkhorn, later recalled that department heads at Lancaster ‘had to deal with young, obviously ambitious and often quite spirited academics, who […] weren’t necessarily […] easy people to boss about or control’.4 The History Department certainly had its disputes, and rightly so: disagreements are often productive. In fact, the predecessor of our University’s Regional Heritage Centre, the Centre for North West Regional Studies (CNWRS), partly came about as the result of a disagreement between John Marshall and Harold Perkin.

Marshall and Perkin both held strong convictions about their subject, and both were engaged in the study and teaching of social history. Both, moreover, recognised the need for university researchers to ‘think regionally’ about the issues, needs and problems of the area surrounding their institutions.5 So, the CNWRS came into being in 1973 as a way of enabling them to pursue their objectives more effectively. Perkin became a pioneer in social history. He was awarded the UK’s first chair in social history in 1967 and established the Social History Society in 1976. Marshall, for his part, became a leading figure in the fields of regional history and industrial archaeology. His legacy lives on in the work of the Department's Regional Heritage Centre today.

Notes

1 ‘Innovation and Evolution’, p. 178.

2 See L. Le Claire, ‘Austin Woolrych: An Appreciation’, in Soldiers, Writers and Statesmen of the English Revolution, ed. by I. Gentles, J. Morrill and B. Worden(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), pp. 1–17 (pp. 8–11).

3 J. Morrill, ‘Austin Herbert Woolrych 1918–2004’, Proceedings of the British Academy, 153 (2008), 391–413 (p. 401).

4 Qt. in M. McClintock, ‘Innovation and Evolution: Lancaster Learning, 1964–74’, in Utopian Universities: A Global History of the New Campuses of the 1960s, ed. by Jill Pellew and Miles Taylor (London: Bloomsbury, 2020), pp 157–89 (p. 178).

5 Marion McClintock and David Shotter (eds), Serving the Region: A History of the Centre for North-West Regional Studies at Lancaster University (Lancaster: Lancaster University Press, 2006), p. 1.

4. A decade of development and change

By 1969, what had begun as ‘three men and a boy’ had become a Department of two dozen academics. A few years later, that number rose to twenty five and included of a young Ruth Henig, later Baroness Henig, who sadly passed away earlier this year. Henig stands out in the Department’s programme guide for 1973 as our only female academic. She is listed therein as specialising in ‘20th-century international relations, with special reference to the United Nations’, a focus evident in her later publications in international and diplomatic history, including League of Nations: The Makers of the Modern World (2010).1

Henig was also a cofounder and co-author in the Lancaster History Pamphlets project, which enhanced the Department's renown in the early 1980s. The pamphlets produced by the project can still be purchased today and provide concise, student-facing analyses of canonical historical topics.

Henig, however, was not the only woman who made waves in the History Department during its first decades. Around the same time, Elizabeth Roberts began completing a pioneering PhD that involved a wholly new research method, oral history. Her work has since proved pivotal to the emergence of oral history as a field of study and practice. It also underpinned Roberts’s seminal book, A Woman’s Place: An Oral History of Working Class Women 1890–1940 (1984) and her working-class oral history archive.

In terms of its gender balance, the History Department has come a long way since the early ’70s. That is not to say, though, that the historians at Lancaster during our first decade were not diverse in other respects. For one thing, they were an international bunch from the get-go. David Hamer was from New Zealand (as noted in Part 2), and Marcus Merriman was an American. He had been born in Baltimore, and by the early 1970s, he was not the only Yankee knocking around the department. He had been joined by Leon Beier and Bob Bliss. Around this time, moreover, the Department had welcomed another scholar from the southern hemisphere, Ralph Gibson. He had been born in Derbyshire but grew up in Australia, and he went on to become a prominent historian of modern France.

These trends have continued in our own time. Our academic staff in History currently includes scholars from countries including Spain, Israel, Austria, Italy, China, Mexico, Switzerland and the United States. Just this past year, we were delighted to appoint our newest colleague, Dr Baihui Duan, a specialist in the environmental history of East Asia. Many of our British colleagues, moreover, have studied or taught at institutions overseas. All of this has helped ensure that History at Lancaster has come to embrace and maintain a broad outlook. Breadth needs to be balanced by depth, and the depth of our connections with the communities across our region remains a core part of the Department's identity. The decision to rebrand the University’s Centre for North West Regional Studies as the Regional Heritage Centre in 2014 and place it within History has helped ensure this.

Notes

1 History at Lancaster’, History Department programme guide, Lancaster University (1973), p. 17. Lancaster University archive.

5. 'New maps of learning'

The 'new maps of learning' that guided History students during the Department's early years were drawn up in accordance with the broad educational ethos articulated in the first Lancaster University prospectus. Rather than encouraging ‘specialisation on a narrow front’, the University aspired to promote ‘the study of interlocking groups of subjects’ that ‘cross traditional faculty boundaries’.1 This aim was imperative to the design of Lancaster's distinctive three-part Part I programme, which enabled students to explore multiple subjects and even change degrees after their first year. Michael Winstanley (who joined the Department in 1978) has recalled that 'History was always a net gainer' in this process.2

Part II comprised nine courses, which were completed over two years and required four essays each as well as summative examinations. History students completed eight courses in their major subject as well as a 'Free Ninth Unit', which permitted a choice of subjects from across the University. This 'ninth unit' was the only course examined at the end of year two, the other eight being examined at the end of year three.

Second-year History survey courses from the period included options such as 'History of Britain from the 9th to the mid-15th century', 'Renaissance Europe' and 'The Foundations of Modern Science, 1687–1904'. Third-year Special Subjects included selections ranging from 'The Reign of Richard II' and 'Social Problems and Policies in Tudor England' to 'Science in British Society, 1830–1870' and 'The Spanish Republic and the Civil War, 1913–1939'. Alongside these, there were also specialised third-year options like 'The Byzantine Empire to 1204', 'The Regional History of North-West England, c. 1660–1900' and 'The Rise of Nationalism in Africa and South Asia'.

The Department's curriculum has continued to evolve since this period, but much of what distinguished us academically in our first years has remained central to our mission. The Department has continued to champion the history of science as well as international and diplomatic history. We are also still a powerhouse for social history and the home of the Social History Society. In recent years, moreover, new areas of expertise have emerged. We have gained a global reputation for excellence in fields ranging from military and international history to the digital humanities.

In addition to the Regional Heritage Centre, our Department is also home to the Centre for War and Diplomacy (established 2018) and the Digital Humanities Centre (established 2022), both of which promote research, teaching and engagement that affirms the continued relevance and importance of History in Lancaster’s increasingly dynamic and interdisciplinary academic culture. What is more, History colleagues play a leading role in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Health Hub, which facilitates collaboration between researchers in the arts, humanities and social sciences around themes related to health and wellbeing. Collectively, this activity is helping to ensure History’s prominence at Lancaster as we move forward into our next sixty years.

Our University began in an era of expansion and innovation in British higher education. Now, three score years later, we are engaged in making major innovations as part of the University’s Curriculum Transformation Project. Yesterday’s ‘new maps of learning’ are being redrawn to meet the needs of the present generation. What the University will look like in sixty years remains to be seen. However, thanks to the enterprising spirit of colleagues past and present, History, as one of our founding subjects, will continue to have a place within it.

Notes

1 University of Lancaster, Prospectus 1963–64 (Lancaster, October 1963), pp. 11–12.

2 Email communication from Michael Winstanley, 17 September 2024.

Memories from our first 60 years

We were delighted to hear from History graduates over the course of our anniversary year, as well as from current and retired members of staff. We are especially grateful to the individuals below, who have given us permission to share their recollections.

Professor Corinna Peniston-Bird

I joined the department when it was 35 years old, first as a Research Associate and then as a Lecturer. I was appointed as the latter when the department was being led by the social historian Eric Evans. Eric was an impressive leader not least for making sure that he benefitted from the viewpoints of those likely to disagree with him. The only other female academic in History when I arrived was Sarah Barber, who rapidly became both a colleague and a friend, and with whom I co-taught and co-published (the MA module and edited collection History Beyond the Text). I always found it peculiar that undergraduates saw nothing odd in the gender balance of the staff even though the student body was much more equally divided. The Department has a very different profile now, although it has still only had one female head in its history, Ruth Henig, Baroness Henig, who sadly died recently.

I learned a great deal about collegial relations working closely with members of the Professional Services team, particularly when the Part I office in the Furness Building was the site of the staff pigeonholes, the fax (!) and the printer, and thus any concentrated work was vulnerable to constant interruptions. In those days only professors had carpets or office chairs with arms, until new appointments arrived and gained those perks by chance. I loved teaching in my office in Furness, which was designed to ensure wherever the students’ gaze wandered they would learn some relevant history from the postcards, posters and books that lined every square inch of the walls. Teaching spaces are more accessible now though, with appropriate equipment trumping character.

Some of the colleagues who stand out from those early days include Stephen Constantine, who began me on my journey with postgraduate researchers, Mike Winstanley and Sandy Grant, who kindly popped in for chats when I first arrived, and Jeffrey Richards, who always welcomed new staff with a wonderful meal at his favourite restaurant and was renowned for not using email (a passing fad). Alan Warburton had me in stitches within seconds and we enjoyed bouncing off each other in our first year lectures. I awaited the return of Thomas Rohkämer from sabbatical with some trepidation having heard much of his intellect, only for him to become a good friend and academic collaborator also. There were many colleagues about whom we could no doubt swap stories, such as Michael Mullett who began his charismatic lectures with a resonant ‘ladies and gentlemen!’, or Marcus Merriman (for many now, a name on a lecture theatre) one of the department’s original members, who insisted on calling me ‘COR’ before regailing me with stories of his mother’s war experiences. —James Taylor had to toil to get rid of the legacy of his cigar smoke when he inherited Marcus’s office.

And then most importantly there are all the students I have had the privilege to meet over the years. I am invited to follow many of their lives and careers after their years at Lancaster, and I especially appreciate them being in touch, even if (and especially when!) it is to tell me that they still can’t watch films without analysing their gender dynamics. Long may it continue.

Dr Michael Lambert

I studied for a PhD in history at Lancaster University from 2013 to 2017, with Dr John Welshman as my supervisor and Professor Ian Gregory as my internal examiner. My project, ‘“Problem families” and the post-war welfare state in the North West of England, 1943–74’, was funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) in partnership with a voluntary organisation, Community Futures, based in Preston.

The principal source materials for my thesis were the records of Brentwood, in Marple, which was a residential rehabilitation centre for so-called ‘problem families’ from the 1940s to the 1970s. Being able to visit and have a look inside what was Brentwood at 137 Church Lane (now flatlets for older people) at the invitation of the Marple Local History Society back in 2015 was a privilege given that the place was central in my research for so long.

One photo I have from my PhD years is of me and John Welshman setting up our event for 'Campus in the City' in 2014, using some materials from my research and his to try and engage people passing through St Nicholas’s Arcades, in Lancaster, about the history of social care. Although not entirely successful in the end, it was a formative experience for me in public engagement and impact which has been part of my academic identity ever since.

For one thing, the experience paved the way for me to appear on national breakfast television, where I have drawn on research from my PhD to campaign for a state apology for the historic forced adoption of children of unmarried mothers from the 1940s to the 1970s. Instances of this came up directly in files I was using for my research, and these formed the basis of evidence I submitted to a major Parliamentary inquiry on the issue back in 2021.

My undergraduate dissertation supervisor from when I was at the University of Liverpool (2005–08) was also a Lancaster alumnus of old, and he was very pleased to see me return to studying in his old stomping ground when we crossed paths in 2014. Unintentionally, as usual for me, I have also ended up rummaging through the Lancaster University Archives under the guidance of Marion McClintock (the University's living institutional memory) whilst researching the history of how and why social work and medicine developed as subjects here.

I've since tried to bring the new generation of cutting-edge historical research to Lancaster through my roles first in the Department of Sociology and now in the Faculty of Health and Medicine. In 2023, I helped Kyle Melles, a Fulbright Scholar from the University of Washington in St Louis, present work in progress to the Centre for War and Diplomacy. This was thanks to the diplomatic intervention of Professor Corinna Peniston-Bird.

Dr Carole Patterson

I graduated in 1980, having been a member of Lonsdale College. Dr Stephen Constantine was an amazing tutor for my final year option: ‘Social Conditions in Britain, 1918–1939’. He wrote a reference for me to apply to medical school in 1984, and I completed my MBBS in Newcastle in 1990.

Some forty years on, I am still working as a doctor, GP and specialist in palliative care. I currently work in two hospices in County Durham: Hospice Willowburn and St Cuthbert’s Hospice.

Stephen’s passion for the history of the welfare of people was inspiring and his personal support of my wild idea that a history graduate could possibly become a doctor was exceptional.

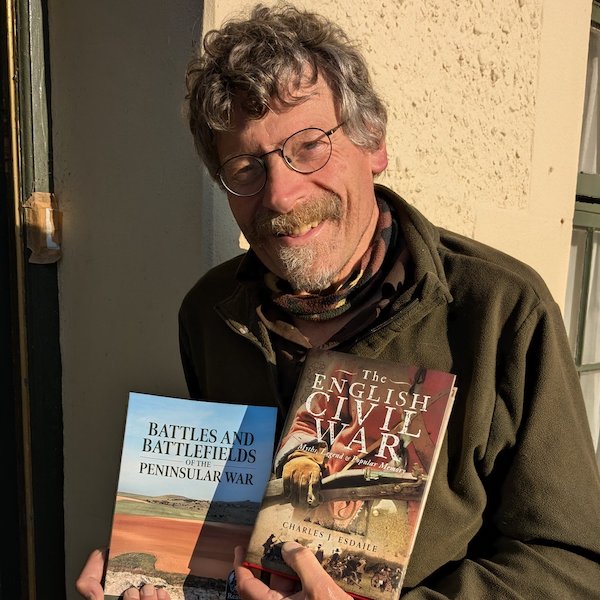

Professor Emeritus Charles J. Esdaile

I first came to Lancaster on 14 January 1977, and you can see the impression it made! I instantly decided it was the place for me. Not only did the academic side of things appeal, but also, as a country boy from a small village, I loved the semi-rural setting. I was thrilled about the opportunity offered by the major-minor system that enabled learning a new language and, still more importantly, the fact that it was possible to study my over-riding obsession of the time, the Spanish Civil War.

All the same, I was still very nervous when my mother drove me up from Surrey the following October, but thanks in part to the kindness of my personal tutor, Dr Stephen Constantine, I settled in well enough and was soon immersed in the mixture of medieval and modern history offered to all freshers. Though not always very happy, I prospered and even managed to win the Queen’s Studentship for 1980; however, honesty now compels me to admit that my crowning achievement was probably avoiding failing Czech, the fresh language that I had eventually settled on!

After a summer spent travelling in Spain, I then embarked on the degree proper. Year two was Tudors and Stuarts, modern Europe, Czech history and a sprawling – yet fascinating – course that brought together southern and eastern Africa and southern Asia via the nexus of the Indian Ocean. In year three, I selected to study Yugoslav history, war and society in modern Europe and I took a Special Subject module on the Spanish Civil War. Along the way I also wrote not one but two dissertations: one on relations between the Basque nationalist movement and the government of the Second Republic between 1931 and 1937, and the other on the myth and reality of the International Brigades. It was a hard, hard slog, but by dint of the unstinting support and encouragement of my tutors (see below), I did well: well enough, indeed, to be accepted for the PhD on which I had long since set my heart.

So much for my studies. What of the people who taught me? Thanks to the major-minor system, not all my work was done in History; I also had to answer to the long-defunct Department of Central and South-East European Studies (a sad loss of the post-1979 cuts, and also, along with Russian, a most unfortunate one given what was to come in 1989). So, I didn’t come across as many members of staff as other people, but Austin Woolrich, John Mackenzie, John Gooch and, especially, my Special-Subject tutor, Martin Blinkhorn, are all figures whom I remember with a huge amount of respect, gratitude and affection: their kindness, scholarship, patience, good counsel and, above all, faith in me are things that will live with me.

In fairness, work hard though I did, life wasn’t all grind. There was probably more I could have done in terms of extra-curriculum stuff, but one thing I did do was to enlist in the ranks of the Sealed Knot, the great English-Civil-War re-enactment society founded by Brigadier Peter Young. It’s still going strong today. The result was many adventures (some of them quite frightening), but also many lasting friendships and, in addition, a series of alternative insights into the past which are incorporated into my latest book, The English Civil War: Myth, Legend and Popular Memory.

My latest book? Well, yes: again at Lancaster, I went on to do my PhD under Martin Blinkhorn’s supervision. However, in this respect, things didn’t work out as planned in that I ended up studying something completely different from what I had initially intended. Thus, obviously enough, I had wanted to do something on the Spanish Civil War, but, very sensibly, Martin told me to go away and find something else on the grounds that, with Franco dead just five years before, the field had become overcrowded with young tyros of the likes of your humble correspondent. I honestly think it was the single most important moment of my life: a conversation which changed everything at a stroke and set me on a path which opened the way to successes of a sort to which I could never have aspired otherwise.

For this, as so much else, I cannot thank Martin enough, while it was to him, too, that I owe both the doctorate I went on to obtain and, in large part, the academic career that I went on to enjoy at the universities of Southampton and Liverpool. The subject we eventually came up with was the origins of the military praetorianism that was so much a feature of Spanish politics from the end of the Napoleonic period right up till 1936. This, in turn, lead me to a specialisation in Napoleonic Spain that was to form the bedrock of my list of publications right up to my retirement in 2020 and, indeed, beyond. That said, I did eventually return to the Spanish Civil War, writing two books on the conflict that I hope represent a genuine addition to the historiography while also returning to certain themes that I had flagged up in my two undergraduate dissertations. Insofar as this is concerned, could there be any greater tribute to the teaching I received at Lancaster?

An academic is generally a teacher as well as an author, of course, and, in this respect, too, I recognise that Lancaster had a great impact. The open-door policy that I met at the hands of Martin and his colleagues is something that I strove hard to emulate until the day of my retirement. I hope that I achieved at least some good along the way. If I did, it was Lancaster that provided the model.

To conclude, then, I am so very happy that I went to Lancaster and remain hugely proud of my connection with the place. What’s more, I know that the Department maintains many aspects of its old ethos. Thus, my youngest daughter, Bernadette, was a student in its hallowed halls from 2019 to 2022, and the best efforts of COVID notwithstanding, graduated with a First. Although her experiences are not mine to tell, I know that she was very happy and that I could not be prouder than when I saw her walk across the same stage I graduated on all those years ago: for all that, too, my humble and most sincere thanks.

Professor Clifford J. Rogers

Between 1988 and 1989 I was an exchange student at Lancaster, coming from Rice University. I had the privilege of studying under John Gooch, Martin Edmonds, and Marcus Merriman, including writing a thesis on the relationship between developing military technology and political enfranchisement in the Middle Ages.

Following Prof. Gooch’s recommendation, I then went to Ohio State University to get my PhD in military history. After that I was an Olin Fellow at Yale, then joined the faculty at West Point, where I’ve now taught for 29 years (counting one year as a Leverhulme Visiting Professor at the University of Wales, Swansea).

Because of my chance to work with Dr. Merriman, it was a special pleasure for me when one of my own students, Daniel Berardino, recently won the Merriman Essay Prize sponsored by Lancaster’s Centre for War and Diplomacy.

Professor Emeritus John Hedley Brooke

I write as a historian of science and as a former member of the Department who joined a exciting and rapidly expanding Lancaster University in 1969, when, under the leadership of Austin Woolrych, the Department was welcoming historians with an unusually diverse range of interests and expertise. Austin had already appointed a historian of science, Robert Fox, whose initiative and highly successful teaching of the subject to both humanities and science students was rewarded with two further appointments following my own: Roger Smith, who was to achieve distinction as a historian of the human sciences, and Peter Harman (now deceased), who was to become an international authority on James Clerk Maxwell, one of the greatest British scientists of the nineteenth century.

The degree structure of the University (with its three-subject Part I, its major/minor scheme for Part II and its free-ninth unit) was uniquely propitious for the subject to prosper and for our group to be designated a small ‘centre of excellence’ in one of the first research assessment exercises. As I developed my own interests in the historical interactions between science and religion, I found myself teaching not only budding historians, but also students specialising in the sciences and religious studies. When in 1999, I left Lancaster and became the first holder of the Andreas Idreos Chair in Science & Religion at the University of Oxford, it was a special pleasure to rejoin Robert Fox, who for some years had been Professor of the History of Science in Oxford’s History Faculty and who was subsequently awarded the Sarton Medal: the most prestigious prize bestowed by the History of Science Society.

My 30 years in the department were invariably stimulating and rewarding, and were immeasurably enhanced by having met my wife within the University when she was secretary of the student music society. I particularly valued the college system and became Senior Tutor, and then Principal, of Bowland College. Some memories of early days derive from my membership of the staff cricket team, which surprisingly included some of the university’s most senior figures, including its future Vice-Chancellor, Philip Reynolds, one of its most illustrious professors, Ninian Smart (religious studies), its Registrar, Merton Atkins, and future Registrar Stephen Lamley, then the Admissions Officer. We all played with greater enthusiasm than skill and perplexingly I came to be entrusted with the captaincy, but it was a wonderful way to become acquainted with colleagues throughout the University. The History Department staff was to have its cricket team, which took special delight in beating a team from English. It marked a return to the game for Geoffrey Holmes, then the Department’s most distinguished academic, who for weeks afterwards regaled us with the exquisite stroke he had played on receiving his first ball!

But for a more serious (and yet also comic) memory I recall one of my earliest tutorials in the Department. In my group of five or six (happy days!) I had been allocated the colourful figure of Allan Chapman. Allan was a conspicuous figure on the Lancaster campus not least for his unique sartorial appearance, regularly sporting a three-piece suit complete with bow tie and watch chain – not the typical dress of northern undergraduates at the time. For me this had one memorable consequence. At its first meeting, one member of the group arrived late and, peeping sheepishly around my door, witnessed Allan in full flight commanding attention with his fluency and sartorial authority. Unsurprisingly, the belated recruit immediately inferred that Allan must be his tutor, to whom he apologised profusely for his lateness. Memorable embarrassment all round, though I suspect Allan enjoyed the incident and may have savoured the pleasure of sitting in the tutor’s chair. A first step perhaps towards his eventual life in Oxford with a high reputation as a tutor and public speaker, eventually winning a Lancaster University Alumni Award in 2014.

History Department would like to thank Aimee Wilkinson, Department of History Intern, as well as Rebecca Sheppard, Alison Wilkinson and Christopher Donaldson for their contributions to this page. Aimee Wilkinson's internship was generously sponsored by Lancaster University's Careers and Employability Services.