82 THE STONES OF VENICE CONSTRUCTION

and, in reasoning upon the superstructure, we shall never suppose it to be done. The mind of the spectator does not conceive it; and he estimates the merits of the edifice on the supposition of its being built upon the ground. Even if there be a vast tableland of foundation elevated for the whole of it, accessible by steps all round, as at Pisa,1 the surface of this table is always conceived as capable of yielding somewhat to superincumbent weight, and generally is so; and we shall base all our arguments on the widest possible supposition, that is to say, that the building stands on a surface either of earth, or, at all events, capable of yielding in some degree to its weight.

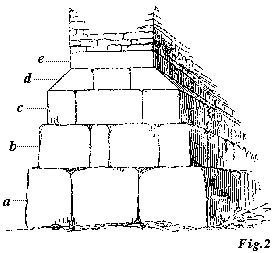

§ 8. Now let the reader simply ask himself how, on such a surface, he would set about building a substantial wall, that should be able to bear

1 [Where the Cathedral is surrounded by a wide marble platform with steps.]

[Version 0.04: March 2008]