462 APPENDIX, 21

ground-plan and elevation being strangely confused in the design. In this pond water is represented by parallel zigzag lines, in which fish are swimming about. On the surface are birds and lotos flowers; the herbage at the edge of the pond is represented by a border of symmetrical fan-shaped flowers; the field beyond by rows of trees, arranged round the sides of the pond at right angles to each other, and in defiance of all laws of perspective.

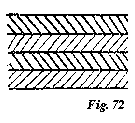

In the fresco, No. 170, we have the representation of a river with papyrus on its bank. Here the water is rendered

In the Assyrian Pantheon one aquatic deity has been discovered, the god Dagon, whose human form terminates in a fish’s tail. Of the character and attributes of this deity we know but little.

The more abbreviated mode of representing water, the zigzag line, occurs on the large silver coins with the type of a city or a war-galley (see Layard, ii. p. 386). These coins were probably struck in Assyria, not long after the conquest of it by the Persians.

In Greek art the modes of representing water are far more varied. Two conventional imitations, the wave moulding and the Mæander, are well known. Both are probably of the most remote antiquity; both have been largely employed as an architectural ornament, and subordinately as a decoration of vases, costume, furniture, and implements. In the wave moulding we have a conventional representation of the small crisping waves which break upon the shore of the Mediterranean, the sea of the Greeks.

Their regular succession, and equality of force and volume, are generalised in this moulding, while the minuter varieties which distinguish one wave from another are merged in the general type. The character of ocean waves is to be “for ever changing, yet the same forever;”1 it is this eternity of recurrence which the early artist has expressed in this hieroglyphic.

1 [Coleridge: Hymn before Sunrise, in the Vale of Chamouni-“For ever shattered and the same for ever.”]

[Version 0.04: March 2008]