184 THE STONES OF VENICE CONSTRUCTION

to me possible that in the East the bulging form may be also delightful, from the idea of its enclosing a volume of cool air. I enjoy them in St. Mark’s chiefly because they increase the fantastic and unreal character of St. Mark’s Place; and because they appear to sympathise with an expression, common, I think, to all the buildings of that group, of a natural buoyancy, as if they floated in the air1 or on the surface of the sea. But assuredly, they are not features to be recommended for imitation.*

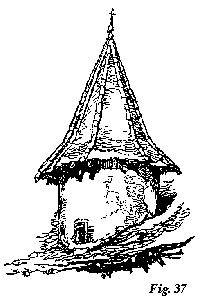

§ 4. One form, closely connected with the Chinese concave, is, however, often

§ 5. The true gable, as it is the simplest and most natural, so I esteem it the grandest of roofs; whether rising in ridgy darkness, like a grey slope of slaty mountains, over the precipitous walls of the Northern cathedrals, or stretched in burning breadth above the white and square-set groups of the Southern architecture. But

* I do not speak of the true dome, because I have not studied its construction enough to know at what largeness of scale it begins to be rather a tour de force than a convenient or natural form of roof, and because the ordinary spectator’s choice among its various outlines must always be dependent on æsthetic considerations only, and can in no wise be grounded on any conception of its infinitely complicated structural principles.

1 [For this effect in the case of the Ducal Palace, see Stones of Venice, vol. ii. ch. vii. § 10.]

[Version 0.04: March 2008]