162 THE STONES OF VENICE CONSTRUCTION

detestable ugliness, wherever it occurs on a large scale. It is eminently characteristic of Tudor work, and it is the profile of the Chinese roof; (I say on a large scale, because this, as well as all other capricious arches, may be made secure by their masonry when small, but not otherwise). Some allowable modifications of it will be noticed in the chapter on Roofs.1

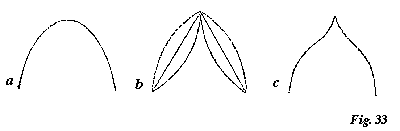

§ 17. There is only one more form of arch which we have to notice. When the last described arch is used, not as the principal arrangement, but as a mere heading to a common pointed arch, we have the form c, Fig. 33. Now this is better than the entirely reversed arch for two reasons: first, less of the line is weakened by reversing; secondly, the double curve has a very high æsthetic value, not existing in the mere segments

|

of circles. For these reasons arches of this kind are not only admissible, but even of great desirableness, when their scale and masonry render them secure, but above a certain scale they are altogether barbarous; and, with the reversed Tudor arch, wantonly employed, are the characteristics of the worst and meanest schools of architecture, past or present.

This double curve is called the Ogee: it is the profile of many German leaden roofs, of many Turkish domes (there more excusable, because associated and in sympathy with exquisitely managed arches of the same line in the walls below), of Tudor turrets, as in Henry the Seventh’s Chapel, and it is at the bottom or top of sundry other blunders all over the world.2

1 [See below, ch. xiii. § 3, p. 183.]

2 [For Ruskin’s other criticisms of this chapel, see Seven Lamps, ch. iv. § 8 (Vol. VIII. p. 146).]

[Version 0.04: March 2008]