Shorthand

(‘a man yt coulde write’):

That is, a shorthand writer. The early seventeenth century saw the popularisation of shorthand, which was immensely useful for making verbatim reports of, among other things, court cases.1 Quakers published detailed reports of their confrontations with the law: see, for example, Francis Howgill's trial at Appleby on 22nd-23rd August 1654 published in Besse Sufferings 2 (London: Hinde, 1753) 14-17. These are tidied up for publication, but the transcript of the hearing against George Fox on a charge of blasphemy (Long Journal fols 45r-49v) reads like a modern-day Linguistics transcript, with all the original ellipses and hesitations, and must have been taken down verbatim.

When Fox and his companions were in Launceston jail in 1656, ‘wee sent for a younge woman (one Anne Downer) from London who coulde write caracters to gett & dresse our meate & shee was very serviceable to us’. (According to George Whitehead, later her husband, she walked the 200 miles to Cornwall.) She was the daughter of a clergyman from Charlbury, and clearly well educated: she later became a notable Quaker minister. Her serviceableness consisted in her secretarial as well as her cooking skills.

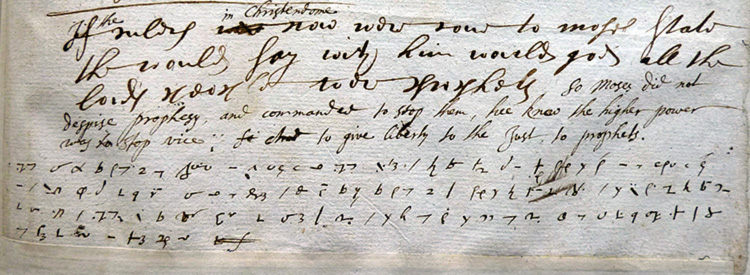

This short passage from the Spence MS (Long Journal) is at the bottom of a letter dated 1660 about the persecutions of Sir George Middleton:

Spence MS fol. 255r

1. See D. G. Lister 'Shorthand as a 17th century Quaker tool: some early shorthand systems and their use by Friends' Journal of the Friends Historical Society 51.3 (1967) 154-8.

Close this window to return