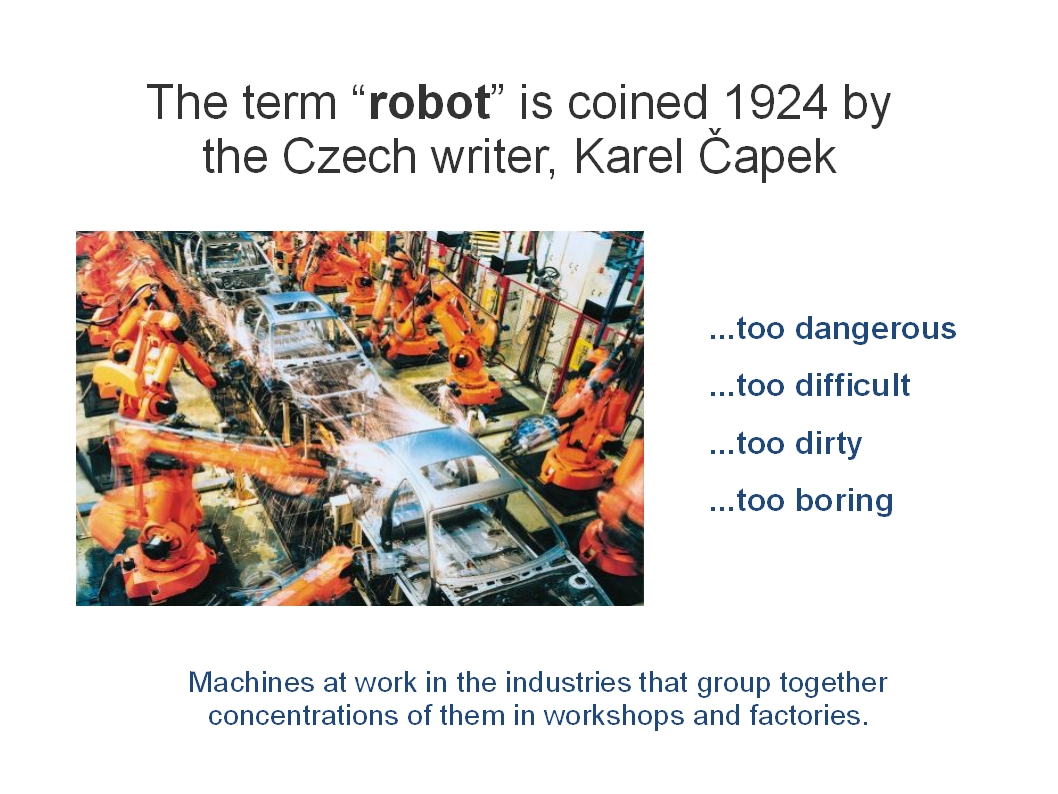

The "robot" as we know it today can be of many different types. For example, millions of automatons have been put to work over the past decades in the industries. These industrial robots operate according to prescription and mainly in designated areas that are fenced off from human access. The work they carry out is carefully circumscribed with finite options, local to specific work stations, and so on—work that is typically considered too dangerous, difficult, boring or dirty for humans to do.

Meanwhile, Artificial Intelligence (AI) research emerged in the latter half of the twentieth century, the first generation AI drawing on a representational model of mind with heritage in Cartesian mind-body dualism. In crude terms, it says that humans build a model of the world in the mind and that any understanding of what is the case, what to do or how to interact will have to take place with and through this model. Accordingly, AI researchers were encoding functional representations of "world models" to test if these intelligence models could produce correct responses to input. The intention was to create general problem solvers which could interact meaningfully with humans and, eventually, operate in the "wild" among them.

There is no sign of the general problem solver, and the representational model of mind has given way to designs of neural networks and different types of "learning" systems. But the human agent continues to be explained, according to cognitive science, on the basis of processes in the mind (or brain), and interactions with world on the basis of input/output functions, information processing theories, cognitive control structures, mental models, and the like (Carroll 2003). In other words, cognitive science is a study of isolable agents with specifiable attributes and resources. And, AI and Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) researchers, who draw upon cognitive science, work with formal descriptions of knowledge and tasks.