Annette Kuhn goes on an archival quest

Late last year BBC Television broadcast a six-part drama series called Boat Story (BBC1, November 2023), one of whose stars was Daisy Haggard. The surname rang bells–not so much because of the actress’s previous TV roles (Uncle, Episodes, Back to Life) as for its connection with one of Cinema Culture in 1930s Britain’s participants. This association was relatively fresh in my mind because I had spent many weeks at home during Covid lockdown, working through transcripts of the interviews that were conducted for CCINTB back in the 1990s, checking and standardising them in preparation for their launch on the CMDA website. As part of this task I researched and composed home pages for participants, immersing myself in their memories—a productive distraction from pandemic ennui.

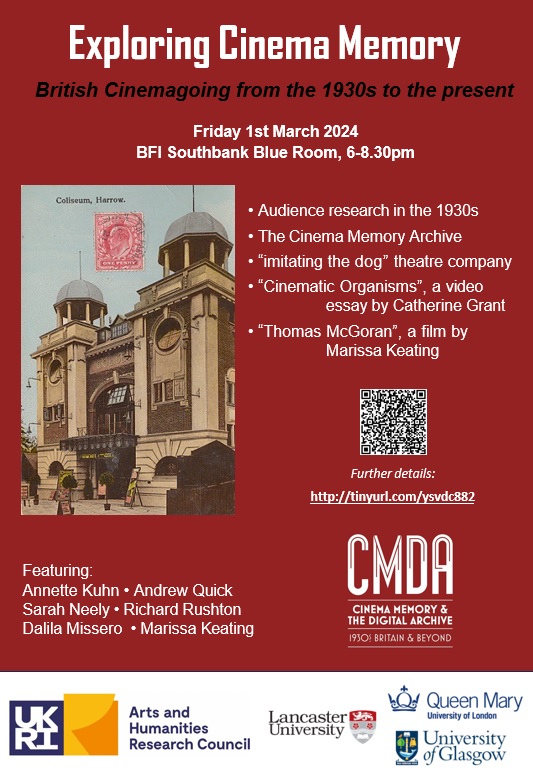

In August 2020 I was working on the interviews conducted with men and women living in the London suburb of Harrow. Among these is CCINTB’s only upper middle-class interviewee, Beatrice Cooper, who was born in Hendon, North London, in 1921: recalling her earliest visit to the cinema as a five-year-old, Mrs Cooper tells the interviewer that she was accompanied by the family’s maid. The film they saw together in a cinema in Kentish Town was Seventh Heaven (1927).

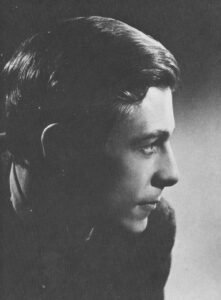

Having studied at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama in her teens Mrs Cooper was exceptionally au fait with the prewar worlds of British stage and screen, and one of the many film personalities referred to in the course of her two interviews is Stephen Haggard. This name was new to me. It turns out that, besides being a descendant of the nineteenth-century novelist H. Rider Haggard, Stephen Haggard founded a theatrical dynasty. Boat Story’s Daisy Haggard, daughter of television, film and stage director Piers Haggard,[1] is his granddaughter.

“I was fascinated by Stephen Haggard”, declares Mrs Cooper; and the memories of the actor that she shares are certainly intriguing. She recalls autograph hunting as a young woman growing up in North London in the late 1930s:

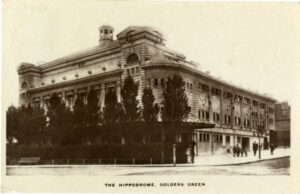

Beatrice Cooper: Erm, because at that time, I used to go very often. And eh, yes, erm, then, I was a real theatre, filmgoer. I used to go a lot to the Golders Green Hippodrome […]. And I used to wait outside the stage door and get their autographs. I’ve still got that actually–

Interviewer: Mhm.

BC: A book with all their autographs. And a wonderful actor called Stephen Haggard. Now he was in a play by Shaw, ‘Candida’. This was just before the war. This must’ve been 1938. And he had been in several films, but he was mainly a stage actor.[2]

In her second interview Mrs Cooper shows the interviewer her autograph book and alludes to this encounter again:

BC: Erm, [I] met him outside the Hippodrome. […] I was with my sister. And she had already seen eh, the play with Diana Wynyard and the one that we saw at the Hippodrome was with him and Ann Harding. And she said that she’d seen the previous one with Diana Wynyard. And he said, “Well who did you prefer?” And she said, “I think I prefer Ann Harding.” And he said, “Oh well, you obviously have a knowledge of the fundamentals.”

Int: Aw!

BC: And she was very chuffed by that–

Int: [laughs]

BC: And off he went in his little car.[3]

A compelling instance of memory-talk, with Stephen Haggard at its centre, unfolds around this recollection. Several versions of the story, and of the associations attaching to it, recur across Mrs Cooper’s interviews. As Mrs Cooper tells it (“It was very strange, actually”),

BC: I read a book about [the artist] Chagall and discovered that Chagall had a mistress for seven years. And had a child by this lovely woman. And then when I read the book, there was a photograph in there of Stephen Haggard. Well of course, she had written the book and her name was Virginia Haggard. But I didn’t connect the two. […] But going with that photograph that was in there I realised that she was his sister. And erm, I wrote to her and eh, and we had quite a correspondence. Because I was fascinated by Stephen Haggard.[4]

BC: I erm, you know, I was in touch with his sister because his sister lived with Chagall for seven years. And erm–she wrote a book. About those seven years. […] About her life with Chagall. And reading it and looking in the book. It was a second-hand book. I saw a photograph of this Stephen Haggard who was her brother. And erm, I was so amazed by this, I wrote to her and I told her my memories of having met him, outside the Hippodrome.[5]

In literary theory, a distinction is made between story time (the timeframe of narrated events) and plot time (the duration of the telling). Mrs Cooper’s story about Stephen Haggard spans the period from the late 1930s, when she sees him in a play and gets his autograph, to the occasion of coming upon a book written by his sister and entering into correspondence with her. Since the book in question was published in 1987, Mrs Cooper would have made the discovery only a few years before she was interviewed for CCINTB in 1995. While the story spans five decades, then, its telling condenses these years into a couple of (albeit repeated) sentences, bringing together the teenage fan of the distant past and the septuagenarian interviewee of the moment of recollection. But it is a bittersweet moment, for the pleasures of reliving a youthful encounter with the actor and of sharing the remembered experience with someone close to him mingle with a memory of tragedy and a lament for what might have been:

BC: I was fascinated by Stephen Haggard. If he had, unfortunately, he was killed during the war. […] If he had lived, he would have been an absolutely brilliant actor. I remember his performance in ‘Candida’. And eh, meeting him afterwards. Eh, at the stage door. And, he was shot during the war.[6]

BC: And off he went in his little car. And then I think, shortly after that, he joined the army. Well! He didn’t actually. He worked in Bush House as erm, broadcaster to Germany. […] It’s a whole sad history actually. He was murdered eventually. During the war.[7]

BC: I saw him in a play at Golders Green Hippodrome. It was a Shaw play and eh, he was absolutely brilliant. Did I tell you about it?

Int: You did. You mentioned him. Yes. […]

BC: And eh, he was killed in the war. He was murdered actually. Erm, which is very tragic because I think he was just, well…. [8]

Mrs Cooper’s thrice-told tale of an actor’s death is brief in relating its salient details. It is clearly and consistently narrated. It was wartime; he was shot; he was killed; he was murdered. Considered against the ways a soldier might typically lose his life in wartime, Stephen Haggard’s fate comes across as exceptional, not only because of the tragic nature of the event itself but also in its stark and dramatic mode of telling. What happened?

*

An archival quest beckons, the obvious starting point being the man’s war service details in the public records. A certain amount of delving in the UK National Archives (TNA) can be done remotely, but while the collection catalogue can be searched online from home, the records themselves are largely undigitised. There is indeed a file on Stephen Haggard’s wartime service. It is in the personnel records of the Special Operations Executive, and an in-person visit to TNA in Kew, West London, is required in order to view its contents.[9] But this is the Summer of 2020: a global pandemic is in progress and there is no vaccine. Nobody is going anywhere if they can help it. And so it was not until the following April that I was emboldened to make the journey to Kew from my base in the North of England.

The TNA catalogue entry indicates that the contents of Stephen Haggard’s file cover the years between 1939 and 1946, but most of the documents I find in it are dated 1942 or 1943. The record shows that in June 1940 Haggard joined the ranks of the Devonshire Regiment and in October that year moved to the Intelligence Corps, where he was quickly promoted to Captain and seconded to the BBC where he remained until April 1942, working as Programme Assistant, German Forces Programme (Haggard was a fluent German speaker) and being paid by the BBC for the last twelve months of his service there. In May 1942 he asked to join the Middle East and Balkan Mission. “He is to fulfil the duties of The Director of Programmes, SOE European Station”.[10] The SOE functioned during World War 2 to promote sabotage and subversion and assist resistance groups in enemy-occupied territory.

Other sources indicate that he was initially based in Jerusalem for a few months before being transferred to the Department of Political Warfare (PWE) in Cairo just before Christmas 1942,[11] and that in early February 1943 he was transferred to the Political Intelligence Department of the Foreign Office, “which has a branch organisation in the Middle East.”[12] Captain Haggard was clearly doing a lot of travelling around Egypt and Palestine in these months, though his duties and activities are not detailed in his personnel file.

In March 1943 an exchange of letters took place between his offices in Jerusalem and Cairo and the War Office Casualty section in Liverpool. The events leading up to his death are set out in a letter from his Commanding Officer in Jerusalem (“I was Haggard’s O.C. from October to the end of December when he moved to P.W.E. in Cairo”) dated 7 March and marked “MOST SECRET”:

“I think I was the last person to see Captain Haggard before he left Jerusalem, since he left my house in my car and went direct to the station.

“He had lunch with me before going off to the train and was in a perfectly cheerful frame of mind, although he said how extremely tired he was.”[13]

It was on this train–taking him from Jerusalem back to Cairo–that Stephen Haggard met his death on 25 February. A telegram from Cairo dated 27 February states that he committed suicide, though “court of enquiry not yet held.” Correspondence over the ensuing two months alludes repeatedly to the court of inquiry, with some impatience expressed by the War Office (“On the 21st March we again cabled Middle East requesting them to expedite a reply to our enquiry of the 8th March, but have to date received no reply.”[14]) No official verdict is on record in the file, though, its final reference to the matter being a note dated 19 May to the effect that nothing had been made known in Cairo but that the PWE in London knew what the court of enquiry’s findings were. Other documents in the file suggest that there was some confusion over which department Captain Haggard was attached to at the time of his death (and therefore who was paying him and who was responsible for his pension), and also that the Political Intelligence Department was unaware that he had been transferred to them.[15]

And so the manner of Stephen Haggard’s death—murder. assassination or suicide—seems to have remained uncertain in the muddle of war and in buck-passing and mix-up among the various agencies involved, most of which had a stake in secrecy and/or, more mundanely, in saving money.

*

Those who were closest to him differ in their conclusions, some accepting that the truth will never be known. Writing just a few years after his friend’s death, Christopher Hassall sets out a detailed account of Haggard’s last visit to Jerusalem. About events on the train back to Cairo Hassall concludes:

He stepped into the corridor. And there, shortly after, he fell. […] No-one came forward as an eye-witness, and therefore such evidence as there was must leave the manner of his death unproven.

He adds, however:

There was certainly motive enough to incite an agent of the German minority to the risk of removing one whose advocacy of the Allied cause was daily becoming better known.[16]

No further third-party accounts appear until the 1980s, by which time the verdict of suicide had become accepted in some quarters. In her 1989 memoir Cairo in the War, Artemis Cooper observes that while it is a work of fiction Olivia Manning’s recently published The Levant Trilogy (about a newly-married English couple, Guy and Harriet Pringle, who are caught up in the war in the Middle East) is broadly based on its author’s wartime experiences. Among the novels’ characters and the real-life individuals on which they are based Artemis Cooper names Stephen Haggard:

Olivia Manning recorded a curious death which actually happened. The figure of Aidan Pratt is based on a real life actor called Stephen Haggard. Before the war he had been hailed as one of the most handsome and promising classical actors of his generation. […] Stephen Haggard shot himself in the corridor of a train travelling between Jerusalem and Cairo, in February 1943.[17]

However, in My Life With Chagall, the 1987 memoir Beatrice Cooper refers to in both of her interviews, Stephen Haggard’s sister Virginia suggests otherwise: “He had been sent to the Middle East in the intelligence service and was killed there in 1943.”[18] Beatrice Cooper’s choice of words (shot, killed, murdered) suggests that she takes a similar view. In a second memoir, completed by family members and published in 2009, three years after her death, Virginia Haggard elaborates on her brother’s wartime service in the Middle East, alluding to the “heavy and responsible work in Cairo” with which he was tasked at the end of 1942: “A few weeks later came the dreadful news: Stephen had been shot in the train that was taking him from Cairo to Jerusalem [sic].”[19]

According to Virginia Haggard, his widow believed that he had committed suicide: along with reports of a stressful workload there were rumours of an unhappy love affair. She adds that his parents, “who should be left to believe what they wish” … “are convinced that he was killed by the enemy but the official verdict is suicide.”[20]. Oddly, the suicide verdict is foreshadowed in March 1943 in a note from Cairo in Stephen Haggard’s TNA file, which states that the findings of the court of inquiry were not yet known, but suggests that the outcome has been unofficially decided: “Understand finding will be that he ‘took his life under strong provocation in moment of mental aberration’.”[21] This is the version currently given in most potted biographies of Stephen Haggard.

*

As already noted, the precise nature of Stephen Haggard’s job in the Political Warfare Department is not detailed in his TNA file. As an intelligence officer with a background in broadcasting and with the job title of Director of Programmes , it can be assumed that he continued in this line of work; and on the subject of broadcasting there is an intriguing passage in The Levant Trilogy. While travelling in Palestine, Harriet Pringle comes across a Cairo acquaintance called Lister who is on his way to Jerusalem on a “hush-hush” mission: “Everyone knows about it, of course. Everyone knows everything here.”

The other day I got into a taxi and said to the driver: “Take me to the broadcasting station.” “What you want, sah?” he asked. “You want PBS [Palestine Broadcasting Service] or want Secret Broadcasting Station?” I said: “How d’you know there’s a secret broadcasting station?” and the fellow roared with laughter: “Oh, sah, everyone know secret broadcasting station.”[22]

Harriet proceeds to Jerusalem with Lister, but eventually decides that she must return to Cairo. Seeing her off on the train, Lister says:

“I’m afraid I’ve bad news for you, Harriet. Your friend Aidan Pratt has been shot.’

‘But not dead?’

‘Well, yes. It was on the train coming back from Cairo. In the corridor.’

‘Who would shoot him? He had no enemies.’

‘No, no enemies. He shot himself’.”[23]

*

Real-life events and fiction collide in CCINTB interviewee Beatrice Cooper’s account, too:

BC: And really, his life would make the most marvellous film. And his sister’s still alive. And I contemplated contacting her and suggesting it. Make a wonderful, wonderful film. I’ve already cast the main actor [..]. Erm, whose name I can’t think of. Erm, yes. Erm, Emma, Emma Thompson’s husband. What’s his name?

Int: Ah! Yes, erm, Kenneth Branagh.

BC: Kenneth Branagh.

Int: Yeah

BC: He’d be a marvellous star for the part.[24]

In 1987, BBC Television broadcast Fortunes of War, an award-winning serial dramatization of Olivia Manning’s cycle of six novels—The Balkan Trilogy as well as The Levant Trilogy. The protagonists, Guy and Harriet Pringle, are played by Kenneth Branagh, then aged 26, and Emma Thompson. The talented and glamorous couple famously met whilst filming the series and married two years later. In 1995, naming Branagh to star in a biopic about Stephen Haggard, Mrs Cooper surely has Fortunes of War at the back of her mind. In it, Aidan Pratt, the fictional character said to be based on Stephen Haggard, is played by Greg Hicks. Who might be cast today in the film that Beatrice Cooper envisions?

In memory of Karen Vibeke Jorgensen, 1947-2022

Beatrice Cooper’s interviews can be accessed in both audio and transcript via links on her home page on the CMDA website. All Cinema Memory Archive (CMA) items referred to may be consulted in both physical and digital form in the CMA at Lancaster University, by appointment with Special Collections.

If you wish to cite and/or re-use any of CMA materials, please consult the CMDA website for information on copyright and using the materials from the collection and for a citation referencing guide.

[1] Ryan Gilbey, Piers Haggard obituary, Guardian 30 January 2023: https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2023/jan/30/piers-haggard-obituary [accessed 17 March 2024].

[2] Beatrice Cooper, Harrow, 20 July 1995. BC-95-208AT001. Cinema Memory Archive. Stephen Haggard’s feature film credits are Whom the Gods Love (Basil Dean, 1936), Knight Without Armour (Jacques Feyder, 1937), Jamaica Inn (Alfed Hitchcock, 1939) and The Young Mr Pitt (Carol Reed, 1942).

[3] Beatrice Cooper, Harrow, 27 November 1995. BC-95-208AT002. Cinema Memory Archive.

[4] Beatrice Cooper, Harrow, 20 July 1995. The book in question is Virginia Haggard, My Life with Chagall: Seven Years of Plenty. London: Robert Hale, 1987.

[5] Beatrice Cooper, Harrow 27 November 1995.

[6] Beatrice Cooper, Harrow, 20 July 1995.

[7] Beatrice Cooper, Harrow 27 November 1995.

[8] Beatrice Cooper, Harrow 27 November 1995.

[9] TNA, Special Operations Executive Personnel Files (PF Series), HS9/643/4, Stephen Hubert Avenal Haggard — born 21.03.1911.

[10] TNA-SOE HS9/643/4, note dated 26 May 1942.

[11] Christopher Hassall, The Timeless Quest: Stephen Haggard. London Arthur Barker Ltd, [1948]: 208-211; Virginia Haggard, Lifeline. Milton Keynes: AuthorHouse, 2009: 98, 100; Haggard, My Life with Chagall: 46.

[12] TNA-SOE HS9/643/4, telegraph from Cairo, 4 March 1943.

[13] TNA-SOE HS9/643/4, letter from G.S.I.K. Jerusalem, 7 March 1943; corroborated by Hassall, The Timeless Quest: 217.

[14] TNA-SOE HS9/643/4, letter from War Office Casualty Branch Liverpool to War Office Whitehall, 9 April 1943.

[15] TNA-SOE HS9/643/4, letter dated 8 July 1943.

[16] Hassall, The Timeless Quest: 218.

[17] Artemis Cooper, Cairo in the War: 1939-1945. London: Hamish Hamilton, 1989: 159-160. Aidan Pratt’s death takes place in the third volume of The Levant Trilogy, ‘The Sum of Things’, which was first published in 1980.

[18] Haggard, My Life with Chagall: 40

[19] Haggard, Lifeline: 101, 102.

[20] Haggard, Lifeline: 102.

[21] TNA-SOE HS9/643/4, 25 March 1943.

[22] Olivia Manning, The Levant Trilogy. London: Penguin, 1982: 502.

[23] The Levant Trilogy: 532.

[24] Beatrice Cooper, Harrow, 20 July 1995.