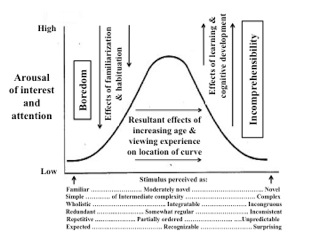

The view that infants prefer stimuli that are moderately discrepant, or different, from what they already know. Originally formulated in the 1970s (Kinney, D.K., & Kagan, J. Infant attention to auditory discrepancy. Child Development, 1976, 47, 156-164), the hypothesis relates stimulus preferences to stimulus representations derived from past experiences. Unlike competing attempts at addressing the nature of infant attention, it can account for novel stimuli in that it treats the formation of new representations as being dependent on existing representations. It suffers, however, from a couple of methodological drawbacks: the nature and number of an infant’s current representations and a reliance on qualitative judgments rather than quantitative measurements of what constitutes a discrepancy. Such drawbacks have led to studies of infant (visual) attention based on statistical learning theory. Other studies have demonstrated that young infants exhibit familiarity early in (visual) processing, with the conclusion being that “… perceptual familiarity-novelty must be carefully disentangled from conceptual knowledge” (p. 491). Beyond the period of infancy, the moderate-discrepancy hypothesis has been applied to how young children attend to the content of television. As with infants, attention is attracted by salient auditory (e.g., applause) and visual (sudden novel image) features, but that there is a shift from attention to salient to non-salient and content features at about 1.5 to 2.5 years of age. This application has been referred to as the traveling lens model (see figure below).