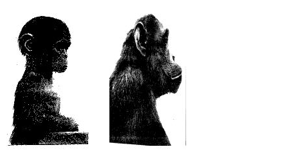

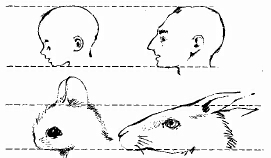

In biology, the study of relationships between size and shape. During mammalian growth, different parts of the body grow at different rates, but in a proportional manner so that body shape is noticeably altered during this period without distorting a recognizable species-characteristic form. There are two forms of allometry: negative allometry in which one body part grows slowly than other (e.g., head grows more slowly than torso), and positive allometry (e.g., legs grow more quickly than torso). See figure below for a further example. Over developmental time, allometric changes also take place in the face such that a full-blown ‘baby face’, as described by Konrad Z. Lorenz (1903-1989), in terms of it being an innate releasing mechanism (IRM), is evident in humans at about 2 to 3 months after birth (see other figure below). According to Lorenz, it serves as an IRM that triggers protective feelings in older children and adults. Some preterm infants may lack a ‘baby face’, contributing to their risk for abuse. It is also used in evolutionary biology to relate changes in body and brain size. The basic allometric formula is expressed as a simple power function