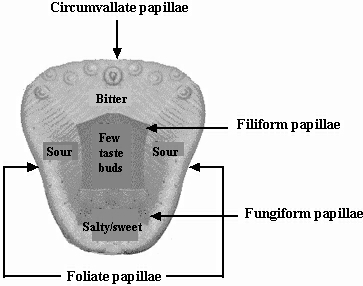

Usually defined in one of two ways, one being the sense of taste and the other the act or process of tasting. In both cases, the tongue is the first port of call for sensing and processing gustatory influences. In general, gustation is the ability to respond to dissolved molecules and ions, in contrast to olfaction that detects airborne molecules. The human tongue consists of four types of papillae: circumvallate papillae (at the back of tongue, organized as trenches in the shape of an inverted V, with taste buds lying deep in the trenches), filiform papillae (distributed across the top of the tongue, but with few taste buds), foliate papillae (a series of folds on the sides toward the back of the tongue in which the taste buds are located deep in the folds), and fungiform papillae (scattered across the top front and middle of tongue, with taste buds found on the surface of the papillae). Taste buds, the smallest functional unit of gustation, are also evident in the roof of the mouth (palate) and the back of the throat as well as the pharynx and epiglottis. The locations of the papillae and the tastes to which they are dedicated are shown in the figure below. Taste buds, specially modified epithelial cells, regenerate every 10 days as do the cells within the taste buds. In fact, gustation is one of only two of the five senses that have the ability to regularly replace cells throughout the life span, the other being olfaction. Each taste bud, of which there are about 4,500 in total, has a pore that opens out to the surface of the tongue, thus enabling ingested molecules and ions to reach the receptor cells inside. Furthermore, the glands of the tongue produce some of the saliva required for swallowing. The receptor cells in the taste buds (about 40 in each) are stimulated by chemicals dissolved in the saliva. When stimulated, these cells depolarise and they synapse with fibers of cranial nerves VII (innervating two-thirds of tongue), IX (projecting to posterior one-third), or X (that innervate the throat, glottis, epiglottis and pharynx). These fibers ultimately project to the thalamus, and from here sensory signals are sent to the primary gustatory cortex situated in the ventral parietal lobe. The ability to taste emerges during prenatal development. Taste buds emerge at 8 weeks gestational age, and by 13 weeks they are to be found throughout the mouth as well as having made connections with invading axons. Subsequently, the number of taste buds continues to increase until after birth. Fetuses can taste certain flavours in the amniotic fluid, especially sweet, but also to degree bitter, by the last two months of pregnancy. After birth, taste shows changes, particularly with regard to salt at about 4 months of age, a delay thought to be beneficial for the development of the kidneys, and again to salt at around 2 years. Despite the changes, taste preferences acquired prenatally as a consequence of maternal diet continue to be maintained for a long period after birth and exert an influence on food preference.