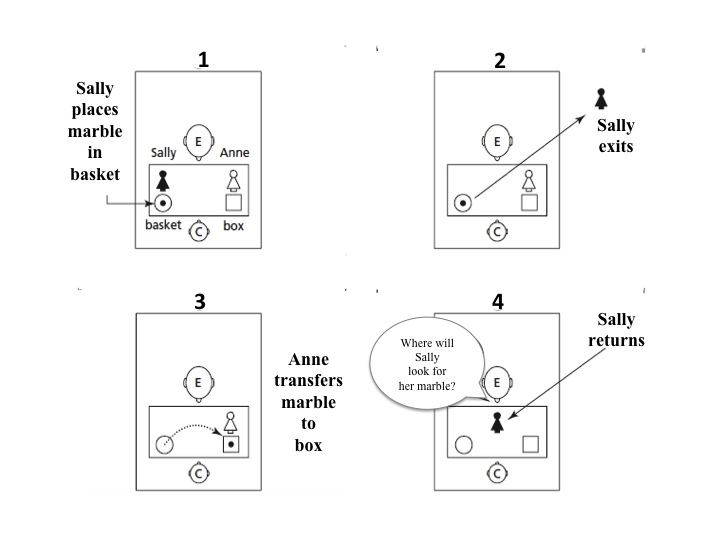

A set of interrelated principles and propositions that explains something of why children think and feel as they do, how they come to understand other people’s minds or mental (beliefs, desires, emotions, imagination, intentions) states, and why and how changes come about. The theory seemingly started with the question “Do the chimpanzee have a theory of mind?” proposed by David Premack and Guy Woodruff in 1978. Since then, it has become a major research enterprise in psychology and cognitive neuroscience, especially in the UK. The original testing ground for ToM involved comparative studies between typically developing children and those with autism. It was a team at University College London who originally took this step, resulting in an influential paper by Simon Baron-Cohen, Alan Leslie and Uta Frith. published in 1985, and entitled ‘Does the autistic child have a “theory of mind”?’ An important component of examining whether a child has a theory of mind is the Sally-Anne test (using dolls) of false beliefs (see figure below for an outline of the procedure). The foundations for this test were due to work of Heinz Wimmer and Josef Perner, published in a seminal paper in 1983. Replacing dolls with human actors delivers the same result (viz., autistic children do not display a fully developed ToM). Other tasks have been devised to test for false beliefs such as the appearance-reality (pr ‘Smarties‘) test, originating with the work of Alice Gopnik and Janet Astington in 1988. Irrespective of task, typically developing children appear to acquire a full-blown ToM (demonstrating empathy and no susceptibility to false beliefs) by the age of 3 to 4 years. Precursors in the development of a ToM have variously been attributed to outcomes using the violation of expectation technique with young infants, and to the acquisition of an understanding of joint attention in 7 to 9 month-olds. From the perspective of cognitive neuroscience, the functions attributed to mirror neurons have been advanced as crucial cortical mechanisms in the expression of a ToM. While there seems to be general agreement that ToM is a domain-specific ability, there is ongoing debate as to what constitutes ‘mind reading’ . One the hand, it is hypothesized to depend on the deployment of a theory akin to naive physics rooted in folk wisdom (and thus is sometimes referred to as ‘theory of theory of mind’ or ‘theory-theory’). On the other, there is the theory of mental simulation, which contends that mind reading involves a ‘simulator’ using a model of his or her mind as the basis of a model of the mind of the ‘simulated agent’. Returning to the question posed by Premack and Woodruff, there is also an continuing debate about whether a full-blown ToM is a unique human ability, or one can be demonstrated in other primates. One interpretation of the available literature is that adult chimpanzees have most of the attributes of a ToM (e.g., understanding the goals and intentions of others), but there is a lack of evidence that they that understand false beliefs.