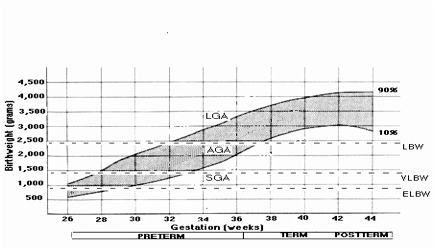

One delivered or born before 37 weeks of pregnancy have elapsed since the last normal menstrual period. There are various ways of classifying and comparing preterm infants. One is based on the absence or presence of age-related risk factors, giving rise to distinctions between low-risk versus high-risk preterm infants, and another is derived from the degree of prematurity, resulting in the identification of very preterm infants. Further distinctions concern birthweight per se, and birthweight relative to gestational age. These result in distinctions between very (extremely) low birthweight (ELBW; less than 1000 grams) and very low birthweight (VLBW; less than 1500 grams) infants and between appropriate- and small-for-gestational age (SGA) preterm infants (see figure below). VLBW form as much one in ten of low birth weights (<2500 grams). Such infants have difficulties in maintaining glucose within the normal range when the maternal source is lost at birth and thus are at risk for acquiring hypoglycemia. The incidence of preterm birth varies between 4% to 9.5% of live births in western countries, with that for very preterm birth being around 0.60%. About 7% of live births are LBW, of which 10% to 15% are VLBW, giving an incidence 0.2% to 2.0%. Among LBW infants, 18% to 40% are SGA. With regard to low-risk preterm infants, an issue of debate is whether additional extrauterine experience in some way accelerates certain aspects of their postnatal development relative to full term infants. Some studies report advanced development related to visual system functioning (e.g., in terms of visual-evoked responses), and for fine, rather than gross, motor abilities. A similar issue arises when consideration is given to those infants with evidence of mild intrauterine growth restriction (i.e., small-for-gestational infants), with some arguing that this condition accelerates lung maturation, among other things.